Alan Ayckbourn’s huge new two-part, six-hour dystopian drama The Divide imagines a world where women and men are segregated.

The play is set 100 years from now. A plague has ravaged the population. Those who have survived live on opposite sides of a divided society. The men wear white while the – still contagious and therefore sinful – women wear black outfits that look like Edwardian mourning attire.

Their lives are governed by a sacred text called the Book of Certitude and the dictates of a mysterious unseen Preacher. Women form partnerships with one another in order to raise children, with one assuming the role of the “MaMa”, the child bearer, the other the “MaPa”, the provider. Heterosexual relationships are considered abnormal and dangerous. People wear masks to avoid contagion rendering themselves eerily faceless.

Brother and sister Soween and Elihu grow up in a village on the female side of the divide in a system that puts far greater value on his life than hers. The 14-year-old Soween and her brother both fancy classmate Giella but she has her sights set on Elihu and the two embark on a forbidden relationship.

The Divide is a strange mix of things: it feels like a novel for young adults fused with bits of The Handmaid’s Tale. It seems to be a commentary on the dangers of equating sex with sin, on religion and social control. But after six long, long hours spent in this world it remains hard to work out exactly what the play is trying to say .

This is in part because the rules of Ayckbourn’s dystopia are frustratingly opaque. Dissident acts appear to include the wearing of high heels and lipstick. Pictures of Renaissance art are considered to be pornographic. Mirrors aren’t allowed. We never discover how the male side of the divide differs from the female one – other than the fact they seem to play a lot of golf over there –or what caused the technological regression that seems to have befallen their society.

Part One opens with a framing scene set years after the fall of the divide in which two academics serve up large chunks of exposition in the form of a history lecture. The bulk of the story is told via Soween and Elihu’s diary entries and through correspondence between various village officials. This means that the characters are forever describing what they’re doing rather than doing things and the play includes more scenes of tedious council meetings than any audience should ever have to endure.

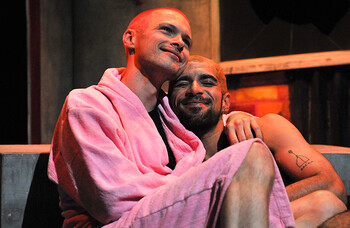

There are times when Annabel Bolton’s production feels like a low-budget Netflix show – only you can’t pause it mid-way through and make a toastie and a cup of tea. Erin Doherty, as the unfortunate Soween, is brilliant – properly, improbably good given the material. She propels the production along through sheer force of personality. Even though her character is forever being banished to her room or forced to drink urine in some weird hazing ritual, she remains buoyant.

The play is set in a world where colour is forbidden and for the most part the staging looks dark and drab. Occasionally a prop or platform is trundled out but for large chunks of the production it’s just Doherty in her black bonnet looking pained as she rattles through acres of narration. Faced with a near-impossible job, Doherty succeeds in making you care about Soween.

Alan Ayckbourn’s The Divide review at Old Vic, London – ‘clunky and insensitive’

While Part One is basically a discount dystopia designed for a tweenage audience – tolerable if tedious – Part Two really dials up the strange. There’s some discussion of whether Elihu might be the ‘chosen one’ and therefore immune from the disease.

Giella and Elihu get married (girls in plague-ravaged future worlds still dream of wedding dresses apparently) and the couple decide to mark their illegal union by having a great big party, which seems like a pretty big dystopia no-no. Everything inevitably goes pear-shaped and somehow – Ayckbourn’s a bit fuzzy on the details – their doomed union ends up becoming a catalyst for the collapse of the whole system.

While on one hand Ayckbourn’s play seems to be saying that everyone should be free to love anyone they want, all people should be equal, and if you impose divisions on people, tragedy will inevitably follow, the whole thing just ends up feeling like an exercise in gay erasure.

One of the more interesting aspects of this whole bloated experience is the single sex, homosocial world that comes about as a result of the divide, but when the wall falls, this whole way of life is abandoned. Soween, who has only known a world where women love women, is swayed by the first dude she claps eyes on.

The Divide raises so many questions. The chief one being: had no one actually read it before deciding to put it on? And did they not notice how regressive the whole thing was? Or question whether it was necessary for it to be six whole hours long?

Length alone does not make for event theatre and, by the end, The Divide feels like a feat of endurance more than anything else.

More Reviews

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99