Duing the gay marriage debate a few years ago, opponents kept trotting out the word ‘complementarity’. It was supposed to privilege the natural pairing between man and woman, and condemn homosexuality as deviant. But it’s a principle that, disappointingly, becomes central to Alan Ayckbourn’s embarrassing dystopia.

When it premiered at last year’s Edinburgh International Festival the play was split into two parts, and ran to six hours. It has been heavily trimmed for its London run to a comparatively epigrammatic three hours and 50 minutes.

It’s the future. After a plague transmitted by women almost killed everyone, men and women have been forced to live either side of a Divide. Women wear black as a mark of their sinful, plague-carrying bodies. They live together as MaMa and MaPa, reproduction is via artificial insemination, and if they have a boy he is sent north of the Divide when he turns 18. But let’s not dig too deeply into the mechanics of this world – Ayckbourn hasn’t.

In a framing device the protagonist, Soween, explains the history of the Divide and her part in its undoing – her brother Elihu falls in love with a woman. The story is told mostly through Soween and Elihu’s diary entries, so every single word of the four hours is exposition.

Ayckbourn brings the world into being by brute force, having these characters monologue endlessly about its half-formed rules. It’s four hours long, and devoid of drama. Four hours long, and the characters never deepen.

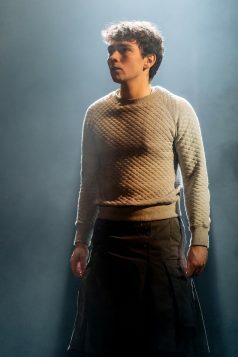

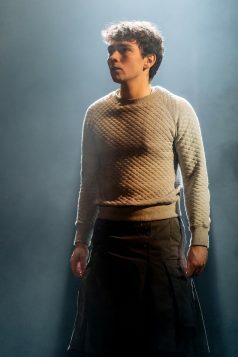

Yet Erin Doherty as Soween, with her pinched voice, manages the remarkable feat of making us feel something for a character who is otherwise just a vehicle for exposition. Jake Davies as Elihu conveys innocence and earnestness, and simple bewilderment at a world he sees as strange and unfair. They are both brilliant.

Director Annabel Bolton makes the very best of this with a darkly beautiful production. Black cloths in receding layers slide up down and across the stage, platforms halfway up the high proscenium arch give a sense of space and grandeur.

The fault is certainly not with the cast and crew. From Doherty and Davies to David Plater’s monochrome lighting to Lucy Hind’s stylised movement everything about it is of a high standard. Except the writing.

What Ayckbourn is trying to do is permanently unclear. Expose the artificiality of gender roles? Point out the hypocrisy of religious zealotry? He does, a little. But, having lived their lives in homosexual societies, when the Divide falls, the men and women are at each other’s loins in an instant.

Most egregiously, the play is ignorant of, or at least omits, trans people and glosses over the fact that some people are actually gay. An attempt has been made to address this since the Edinburgh run, with a photo montage at the end that includes gay couples.

While Ayckbourn is pretty clear that bad things happen when people are oppressed, his message is at the exclusion of pretty much all the letters of LGB and T. Billed as a ‘narrative for voices’, it’s a shame that it ignores so many.

The Divide review at King’s Theatre, Edinburgh – ‘a bloated dystopia’

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99