Justice served: James Graham on adapting real crime stories for the stage

When dramatising recent criminal cases – where the families and friends of victims are still piecing their lives back together – what precautions should a playwright take? James Graham tells Holly O’Mahony how he approaches the adaptation of real-life stories

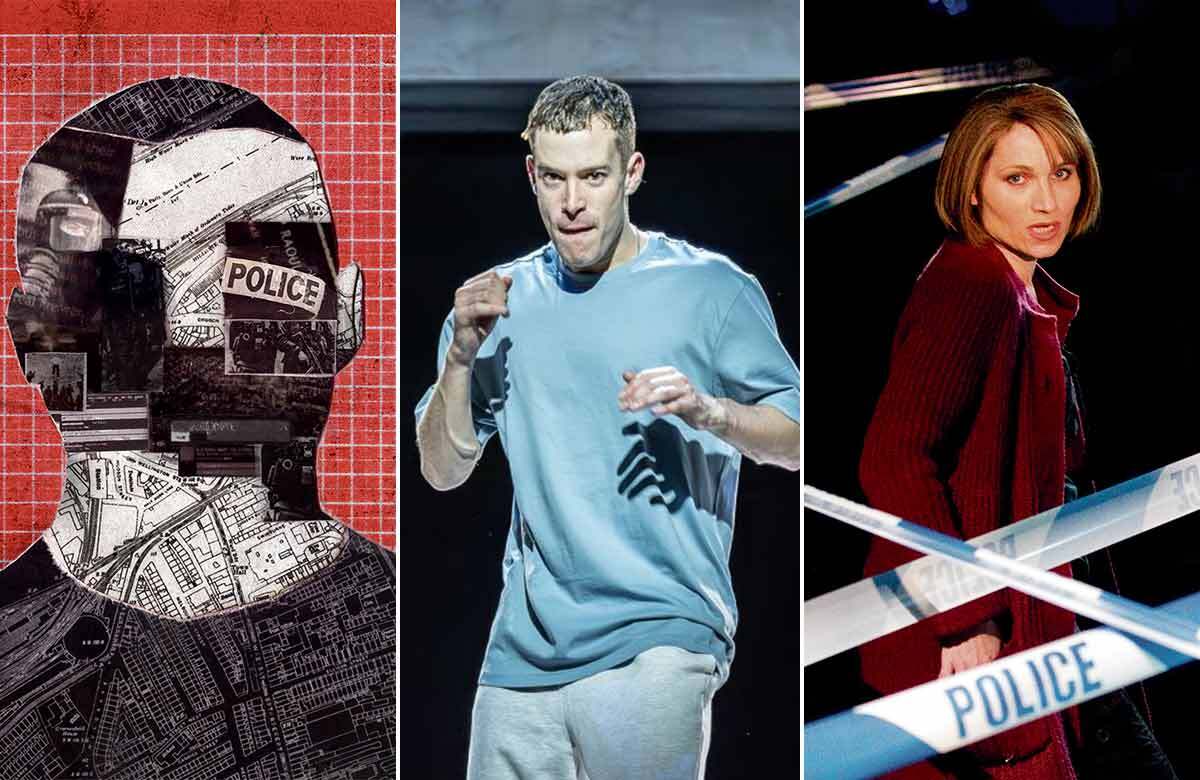

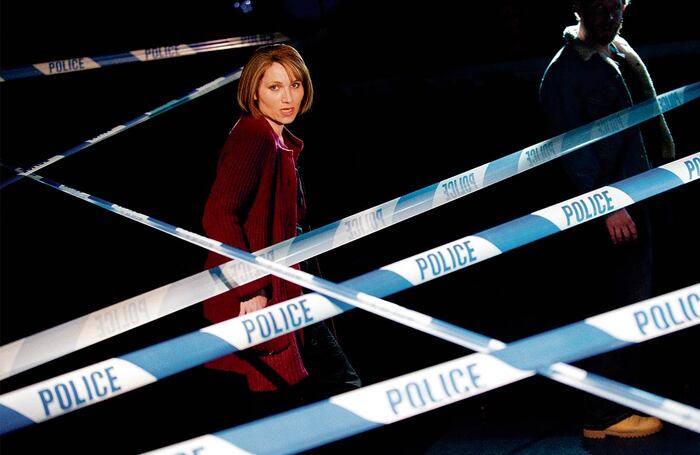

The London stage is getting a triple dose of true crime this season. At the Young Vic, audiences can watch the London premiere of James Graham’s Punch, a dramatisation of a single fatal punch thrown outside a pub and how the perpetrator has since turned his life around. Opening at the end of this month at the Royal Court is writer-director Robert Icke’s first original play, Manhunt, which follows the shocking story of Raoul Moat, who, days after being released from Durham prison in 2010, went on a vengeful shooting spree. Then, in June, the National Theatre lifts the curtain on a revival of Alecky Blythe and Adam Cork’s London Road, a verbatim musical about a community thrown under intense media scrutiny when, in 2006, a resident of their street was found to be the Ipswich serial killer.

But what extra precautions have to be taken when dramatising criminal cases as recent as these – when sentences are still being served and the families and friends of victims are piecing their lives back together?

“Generally speaking, once a verdict has been passed in a court of law, it essentially becomes public record,” says Graham. In other words, you don’t need permission to dramatise these cases because once the details have been made public, your play won’t risk impacting it. But, he cautions: “There are, rightly, myriad moral questions you have to wrestle with when beginning to translate someone’s case – recent or historic – into drama.”

The 42-year-old writer from Nottinghamshire has become known for doing just that – turning the true stories of politicians, televangelists, media moguls, game show contestants, footballers and ordinary people into gripping, often award-winning dramas for stage and screen.

Continues...

He continues to approach his subject matters delicately and with compassion for those personally affected. “My own process is to always get in touch with those involved as soon as possible, particularly when those people are ‘private’ individuals,” he says. “This is what I did with [the BBC One series] Sherwood... Following my conversations with the victims of a tragedy [that unfolded] in my local community, we decided to go in a different direction by renaming and fictionalising the characters and events so that there was some distance for them.”

The extent to which details are changed to protect those involved is considered on a “case-by-case basis”. But the same strictures don’t apply when dealing with prominent figures. “It’s a slightly different matter when you’re dramatising, say, Rupert Murdoch [2017’s Ink] or Dominic Cummings [2019’s television film Brexit: The Uncivil War],” Graham admits, adding that he still contacted both “further down the line”. The justification makes sense. “They – as public figures – have more of an expectation that their roles will be written about.”

‘There is a significant emotional burden – as there should be – to the responsibility of carrying someone else’s story’ James Graham

Punch, which premiered in 2024 at Nottingham Playhouse, is officially described as being “based on the book Right from Wrong by Jacob Dunne”, but Graham insists that while “the book was an incredibly useful source... eventually, my writing became more influenced by my conversations and interviews directly with those involved”. As well as speaking “quite extensively” to Dunne, who served 14 months in prison following his manslaughter conviction, Graham worked with David Hodgkinson and Joan Scourfield, parents of the victim, James Hodgkinson.

“We had to check in with and listen to the questions and concerns of Joan and David... Much like in the play, this began by going through Jacob himself, who has built up a strong relationship with the people he harmed.”

The final product is a play that is as much a remarkable story of forgiveness, on behalf of James’ parents, as one of Dunne’s onward journey, which has seen him turn his life around by gaining a first-class honours degree in criminology and campaigning, alongside Scourfield, to raise awareness around one-punch deaths.

For Dunne and Scourfield, whose work involves retelling their story in prisons and schools, the event that brought them together is presumably often front-of-mind, but in other cases, does a playwright have to be cautious when requesting contact with survivors – or those closest to them – of the risks of reopening old wounds?

Continues...

“My view is that you have to enter those conversations entirely transparently and sincerely. If you’re asking for their guidance, their permissions around certain things, then you have to accept their answers, even if it impacts how you had originally imagined the work. For example, I had imagined that [Jacob, Joan and David] would appear as themselves as characters in the play – but if they had told me they weren’t comfortable with that, I would have totally accepted that and changed my play.” He even went a step further: “I also shared pages and invited them into the rehearsal room to watch a run-through way before we got into the theatre and invited in audiences. Here, once again, we committed to listening to their feedback and responding to what they had to say.”

His advice to budding playwrights hoping to dramatise true stories is simple: “Don’t be intimidated, and don’t feel as though you don’t have the right to take on real stories. Do enter knowing and accepting that you won’t be in control of all outcomes and that there is a significant emotional burden – as there should be – to the responsibility of carrying someone else’s story. I have felt the weight of this many times and never underestimate it.”

He adds: “Try to get all the support and advice from those around you – the theatre, the producers, whoever – and don’t keep worries, questions or anxieties to yourself. Share everything.”

Punch, in part, documents a real-life conviction, and it received a full-circle moment when, in May 2024, a judge referenced the play while sentencing another one-punch case, saying “people need to watch” it. Graham is “pleased that judges and MPs came to see it and found, within a story, a real value that they wanted others to share”.

“It reminds me simply that the power of theatre is empathy. So much of our modern discourse is undertaken on platforms that encourage cruelty – like social media – or occur not in good faith. Theatre is about community – getting people together in a civic space to calmly explore a human story or a particular institution, process or system.”

Punch runs at the Young Vic, London, until April 26. For full details, visit youngvic.org

Opinion

Recommended for you

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99