Mike Bartlett is a playwright who really understands space, and also understands that the act of watching is just as important as the thing being watched; previous productions have seen the audience arranged around the performers like spectators at a boxing match or cock fight.

For Bartlett’s latest play, Game, director Sacha Wares and her regular collaborator, designer Miriam Buether – who both worked on Bartlett’s My Child at the Royal Court – have completely transformed the Almeida. The audience sits in four sections, in a kind of hide, the sort of space in which you might sit while bird-watching or on safari. The stage is concealed behind blinds and a triptych of screens hang above the audience’s heads. Everyone has a headset to wear.

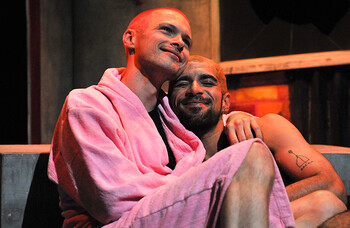

When the blinds lift we find ourselves looking through two-way mirrors into a smart flat around which a young couple, Carly and Ashley (Jodie McNee and Mike Noble), are being shown. Ordinarily it would be out of their price range, but they get to live here without even having to pay a deposit – though they are required to pay a different kind of price: they are the meat in a human shooting range. Periodically people pay to point a rifle at them and knock them out with a tranquiliser dart. Those doing the shooting – a group of lads, a party of women, a prickly school teacher – stand among the audience as they shoulder their weapons and take aim.

There are a lot of layers here – games being played by both the text and the production. It’s more than just a play about the housing crisis (though it comments on that, and on the things ordinary people will accept when they’re desperate). It also touches on the theatre of poverty that characterises shows like Benefits Street and on the rising cult of weaponry which encourages men to spend stag weekends firing guns in Hungarian woodlands.

But while it addresses these themes, it lacks the metal-jacketed clarity, the ballistic precision, of Bartlett’s best work. In Cock and Bull the use of space feels integral to the piece, but here the staging – the headphones, the monitors, the mirrors – while initially exciting, feels complicated.

Kevin Harvey’s David, the man whose job it is to oversee the proceedings, provides a lone note of warm compassion, but his character isn’t given much room to breathe.

For something so short – they’re performing it twice a night – it loses momentum rather rapidly. Maybe that’s half the point: the banality, the ease with which these things become normal.

Dates: February 23 to April 4, PN March 3

More Reviews

More about this person

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99