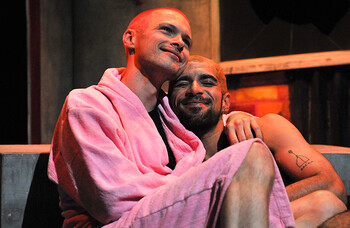

Love, Love, Love

Mike Bartlett’s Love, Love, Love premiered in 2010. Revived precisely a decade later, its central premise of the white boomer middle classes gorging themselves on economic privilege and leaving a crumbling mound of debt in their wake has become a national conversation. Yet Bartlett’s play, rather than feeling like old news, retains both its relevance and its satirical bite.

Sandra (Rachael Stirling) and Kenneth (Nicholas Burns) start out in Act I as weed-loving children of the Swinging Sixties. They’re convinced the world is on the cusp of fantastical change, artistically, politically and sexually, but already their association with extreme privilege and wealth is clear. Both are students at Oxford with the means to spend the expansive summers having wild ‘adventures’ on the Kings Road and across London.

By the time they morph into Reading-dwelling suburbanites in three shades of beige, circa 1990, the hypocrisy of their free-thinking philosophies have become clear: ‘freedom’, to these people, largely means ‘selfishness’. By Act III, set in 2011, their direct refusal to engage with their grown-up daughter’s outright accusations of greed is perhaps less shocking than their own rejection (consciously or otherwise) of the ideals their university-aged selves were meant to stand for.

Rachel O’Riordan directs with a lightness of touch, a slightly slow start giving way to a superbly paced middle section. So much is conveyed through the nuances of the visuals of Joanna Scotcher’s design. We view the 1960s scenes through a curved blob of a rectangle mimicking the boxy television sets of the era. This lens incrementally expands until, in the final scene, we’re at 2010s flat-screen wide-angle coverage.

Stirling delivers a truly excellent performance, equally funny and shocking, as the purely and flagrantly narcissistic Sandra. The absurdity of her character is well balanced by Isabella Laughland’s similarly brilliant performance as Rose, the couple’s emotionally un-anchored musician daughter.

While in charge of the Sherman Theatre in Cardiff, O’Riordan had a continual knack for directing and programming plays that resonated with the theatre’s geography. She’s performed a similar trick here by reviving a play with a particular and specific significance to London and the South East. The ‘generations’ portrayed by Bartlett are, of course, not ‘generations’ at all, but the sub-section of the UK population who benefited astronomically from post-war prosperity and their descendants. Descendants who were perhaps destined to be failed by a way of being, economically and morally, that was ultimately riven with unfairness and inequality.

Ten years after it debuted, what hits home when watching Bartlett’s three claustrophobic domestic scenes play out in cramped, stuffy rooms, is not just the failure of a societal model, but the insularity of its vision all along. Okay, boomer?

Lyric Hammersmith’s Rachel O’Riordan: ‘I haven’t taken a traditional route that’s for sure’

More Reviews

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99