Florian Zeller’s play The Son is the final part of a trilogy, following The Father and The Mother, all of which have been translated by Christopher Hampton. It tells a familiar story. Teenage Nicolas has been playing truant from school. He’s despondent and resentful of his parents’ divorce. But Zeller makes this seemingly routine domestic narrative unfold in a way that feels closer to a thriller.

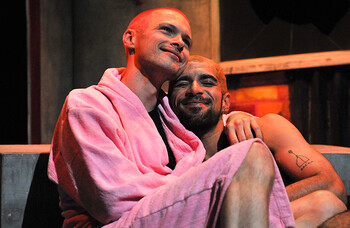

Director Michael Longhurst positions Anne (Amanda Abbington) and Pierre (John Light) on opposite sides of the stage. In the gaping space between them are two presences: their son, Nicolas (Laurie Kynaston), and Pierre’s new wife, Sofia (Amaka Okafor).

Abbington and Light’s curtly polite but agitated exchanges, their awkward attempts at civility, establish the ever-present hum of tension between them. Abbington vibrates with energy. Her character is wound so tight she constantly appears one sentence away from shattering. Okafor, as the new stepmother, provides an obvious contrast, radiating homely warmth. Even when angry, her gestures are fluid and anxiety-free.

As he demonstrated in his production of Nick Payne’s Constellations, Longhurst excels at creating a tightrope between the normal and the abnormal. Kynaston encapsulates this mood, pitching his performance so that his behaviour could either be taken as the average moodiness of a teenager or something altogether more concerning.

Pierre and Sofia’s chic Parisian apartment, beautifully designed by Lizzie Clachan, is invaded by teenage-boy detritus. Nicolas’ mound of discarded belongings are a believable mixture of the adolescent (multiple pairs of Converse trainers and denim jackets) and the poignantly childish (a wash bag decorated with cartoon characters, plastic toys).

The accumulated mess, however, is also symbolic of Nicolas’ inner disarray. He explodes when forced up against the calm and rational world of the adults.

In several ways, Zeller’s play is deliberately ‘ordinary’, both in its content – a divorced couple, a troubled teenager – and in its form. There’s an extremely self-conscious use of Chekhov’s gun and the climatic plot point is signposted well before it happens. Sometimes, particularly in the later scenes, you wish for more ambiguity.

But The Son captivates in its enveloping feeling of inevitability, something that’s aided by Isobel Waller-Bridge’s disconcertingly ominous sound design. While it’s clear exactly what’s going to happen, as with all classic tragedies, everyone is powerless to prevent it. Zeller makes a virtue out of this predictability and the terrifying realisation that screaming louder won’t stop the runaway train.

In this regard, The Son has echoes of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck. The audience waits and waits and waits for the bang, but when it finally comes, it’s still a shock.

Florian Zeller: ‘Theatre is the place for questions, not answers’

More Reviews

More about this person

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99