London’s Gate Theatre at 40: ‘If you’re not brave, you’re not honouring the Gate’s history’

Lyn Gardner

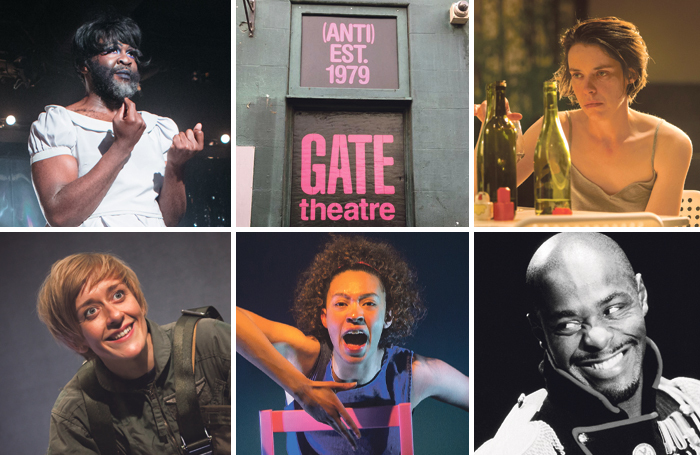

Lyn GardnerFor four decades, London’s Gate Theatre has been the home of dynamic, anti-establishment productions and a springboard for some of the UK’s leading theatrical talent. Lyn Gardner speaks to its current and past leaders about its history, ethos – and where it’s headed next. Pictured above: Gateau Chocolat (Effigies of Wickedness), Caoilfhionn Dunne (Suzy Storck), Paterson Joseph (The Emperor Jones), Nina Bowers (Twilight: Los Angeles, 1982), Lucy Ellinson (Grounded)

Every time the team at London’s Gate Theatre does a get-in or get-out, it discovers grains of red sand in all sorts of unexpected places. The sand dates back to Natalie Abrahami’s 2011 staging of Yerma, which played out Lorca’s tale of passion and yearning on a rusted sand floor. Its continued presence, years after the final performance, is a reminder of the traces left behind by theatre, but it also serves as an aide-memoire of the Gate’s history to those working there, of all those who came before them. The sand is a visible link between the present and the past.

The Gate has a long and rich history, stretching back over 40 years in an improbably awkward and wonky space above a pub in Notting Hill. It’s a space that has been described variously as being like the Tardis in Doctor Who and Mary Poppins’ bag. Fly Davis, who, along with many other leading designers , credits the Gate as being the place where “I learned to fly”, called it: “A glorious black hole in which you can have fun.”

There is no theatre in the country that can mess with an audience’s head or which offers such a visual surprise upon first walking in. Until recently, when the Gate went paperless, those audience members would have had their ticket torn by the venue’s artistic director.

“It is so tiny but it has always looked outwards not inwards,” says the Royal Shakespeare Company’s deputy artistic director Erica Whyman, who was artistic director of the Gate between 2000 and 2004. “And it has always pushed the boundaries of what we think a night in the theatre will be like.”

Giles Croft, who ran the theatre between 1985 and 1990 and went on to become the artistic director of Nottingham Playhouse, says there have been shifts over the years but the Gate remains a theatre with an international perspective and one that is generous about providing opportunities for emerging talent.

“When I was there in the 1980s, there was a sense in which the Gate was always at odds with the mainstream, that it was trying to do something different, and that is as true today as it was then. To do that over 40 years is quite an achievement,” he says.

In 1979, the American director Lou Stein, recently arrived in London with a few plays that he wanted to direct, put an advert in Time Out seeking experienced people, including actors, who would be keen to work at the new pub theatre he was founding in a tiny room covered in flock wallpaper above the Prince Albert pub. “No money, but prospects good,” he declared optimistically.

In fact, it would take more than 20 years and the tenure of Whyman before the Gate became funded by Arts Council England and started to pay the actors and other creatives who worked there with more than a sandwich and their bus fare. But Stein’s confidence was justified in other ways.

At a time when London theatre was insular, and the London International Festival of Theatre not yet founded, the Gate became a place where you could see the rest of the world without leaving W11. A 1991 advert for the theatre proclaimed: “We want to fit the world in our living room.”

Stein’s early eclectic seasons included Flann O’Brien, Mikhail Bulgakov, and American writers Christopher Durang and John Guare. Stephen Daldry, there for two years between 1990 and 1992 before heading off to London’s Royal Court, put on memorable productions of Marieluise Fleisser’s Ingolstadt plays and, in an auditorium that at the time held only 56 people, staged Tirso de Molina’s Damned for Despair with a cast of 26. Money was so tight the male cast members had to share a single pair of thigh-length boots.

Over the years, the global perspective and reinvention continued. David Farr (1995-98) programmed August Strindberg and Georg Buchner seasons, and Abrahami and Carrie Cracknell (joint artistic directors between 2007 and 2012) introduced a new vocabulary of dance and movement to the space. Under their reign, Pierre Rigal performed Press, in which he was a telescoping Alice in Wonderland being crushed by the ceiling, and Chris Goode let rabbits loose on stage in his legendary adaptation of Chekhov’s Three Sisters.

Continues…

10 great Gate shows through the years

When the Wind Blows (1984)

This adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ graphic novel, about an ordinary couple who believe government propaganda that they can turn their house into a nuclear shelter, was brought to the Gate’s stage at a time when anxiety about armageddon was strong, and scepticism about the ‘Protect and Survive’ policy higher.

Danny and the Deep Blue Sea (1985)

A romantic comedy about a pair of New York outcasts was London’s first glimpse of the talent of US writer John Patrick Shanley, who was to gain international recognition two years later with an Oscar nomination for his screenplay of Moonstruck.

The Ingolstadt plays (1991)

Stephen Daldry joined forces with Annie Castledine to direct Marieluise Fliesser’s brilliant dissection of life in bigoted small-town Bavaria among a generation shaped by the First World War and its aftermath. Eager audiences queued round the block for a ticket.

The House of Bernarda Alba (1992)

Katie Mitchell directed Lorca’s last play and did it with such an intensity that it was as if the theatre itself was throbbing with repressed desire and fury at unrealised dreams. A young Emma Rice was in the cast.

Hunting Scenes from Lower Bavaria (1995)

Toby Jones was one of the 18-strong cast of Dominic Cooke’s astonishing promenade production of Martin Sperr’s play set in a small, insular Bavarian village in 1948. Robert Innes Hopkins’ design turned the entire space into a peat-filled barn.

The Flu Season (2003)

US writer Will Eno’s infuriating but also exhilarating and beautiful exploration of the purposelessness of our lives. Soutra Gilmour designed, Erica Whyman directed, and both had enormous fun with a playful meta-theatre show that challenged narrative form.

Eugene O’Neill’s hallucinatory, expressionistic play was given a rare and terrific revival by director Thea Sharrock and designer Richard Hudson, who created a sunken sand-filled pit. Paterson Joseph was superb as the escaped convict from the American South who becomes the dictator of a small island but faces imminent uprising.

The Sexual Neuroses of our Parents (2007)

Swiss writer Lukas Barfuss’ play was designed to push buttons about discomfort around the sexual desires of a teenager with learning disabilities. Carrie Cracknell’s production did just that, teaming up with choreographer Ben Duke to find a physical language that revealed how words are often empty.

George Brant’s searing monologue about a grounded US fighter pilot who is sent to fly remote-controlled drones from the safety of a hut on a base in the Nevada desert was shattering, and came with an electrifying performance from Lucy Ellinson. It bore witness to the fact that war – particularly war waged without moral responsibility – will drive us mad.

The Unknown Island (2017)

Ellen McDougall’s first show as artistic director of the Gate was a gorgeous adaptation of José Saramago’s short story about a man who asks the king for a boat so he can find an unknown island. “Playful and profound” was The Stage’s view about a piece that in execution and Rosie Elnile’s design mined the dynamic of the Gate’s shared space with stage sorcery.

The Unknown Island review at the Gate Theatre, London – ‘playful and profound’

Gateway to success

The roll call of artists, particularly directors and designers, whose early careers have been jump-started by the Gate spans British theatre. A long-standing Jerwood commitment to support new designers has made the Gate a place where early-career designers flourish and find their work is visible for the first time. The Gate’s part in transforming the visual language of contemporary theatre should not be underestimated.

Directors who have worked there make up a who’s who of British theatre. Katie Mitchell, James MacDonald, Ian Rickson, Dominic Cooke, Indhu Rubasingham, Rupert Goold, Joe Hill-Gibbins and Maria Aberg are just a few of those who have passed through. In the last 10 years, those taking a step-up at the Gate have included Lyndsey Turner, Caroline Steinbeis, Justin Audibert, Jude Christian, Tinuke Craig, Caroline Byrne, Lynette Linton and Ola Ince.

“As a history to inherit, it’s a very galvanising one,” says Ellen McDougall, who took over as artistic director in 2017. “It’s never a burden but it does feel when you take over here that a gauntlet is being thrown down because if you are not being brave you are not honouring the history of the Gate. You need to jump off the creative cliff, not memorialise or replicate what has gone before.”

Her predecessor, Christopher Haydon, recently appointed artistic director of the Rose Theatre in Kingston, says: “When you run the Gate you feel very aware that you are part of a line of remarkable people. That’s inspiring but also intimidating. Nobody wants to be the person to break the chain. At the Gate, you’ve got to burn like magnesium, and you burn fast, which is why nobody stays for too long. You get in there, do everything you can, let your imagination run wild and then move on.”

He adds that the Gate is best run by somebody who doesn’t quite know what they are doing. “I mean it. There is something about the energy that comes from doing the AD job for the first time and just giving it a go. As soon as you get to the point that you think you know everything you need to do the job, it’s time to move on.”

Whyman came to the Gate from Southwark Playhouse. Shortly after her tenure, she left to head up Northern Stage in Newcastle. She says that it was at the Gate that she learned to trust her own instincts, other artists’ instincts and not to be swayed by the grumblers who wanted to know why she couldn’t deliver two hits in a row.

“I was pretty sure that ensuring the Gate had two hits in a row was not my job,” Whyman says, adding she was given confidence by a team who supported her and who assured her she needed to be “more Erica, not less Erica”.

She remembers one “rather brilliant” board member arguing: “If the Gate, which is so small that it can never be reliant on the box office, has to have two hits in a row, then all theatre is stuffed. It was at the Gate I realised that there is a kind of work I wanted to make, it wasn’t necessarily going to please everyone but that didn’t mean we shouldn’t do it.”

Funding disputes

If in its early days the Gate was always in a parlous state financially, it was helped by its cosmopolitan location and the fact that locals had an interest in the arts and the money to support a local theatre. Fundraising has always been a big part of the artistic director’s job at the venue. Some proved more adept at it than others. In 1990 it raised £49,000, but when Daldry joined the theatre, his charm and an increased artistic profile meant that in 1992 that figure rose to more than £172,000.

But fundraising alone was never going to sustain the theatre, and when Whyman’s appointment was announced at the theatre’s 21st-birthday party, she was determined to secure Arts Council funding. Her plan did not come without opposition. Many said that the fundraising would collapse if the theatre became part of the Arts Council’s portfolio, the scale and ambition of the work (including cast size) would contract and all the magic would trickle away.

“It’s funny now but it wasn’t funny then,” Whyman says tartly. “I was being told by a group of very privileged people, most of them men, that I would spoil something that had meant the world to them. Who benefited from that magic? The people who could afford to be broke. Of course there was an incredible sense of everyone sacrificing something to be there, but it was also clear to me that it excluded those who couldn’t afford to make that sacrifice and it wasn’t giving us access to the full range of talent that ought to be represented by a theatre like the Gate.”

In 2002, the theatre secured an Arts Council subsidy of £254,000 a year and a deal with Equity that allowed it to pay actors at a rate below Equity minimum. While cast sizes dropped over the subsequent decade and beyond, Haydon points out that the budgets and the investment in actors and creatives went up. The audience remained loyal and adventurous.

“It’s always had an adventurous audience – an interesting mix of an older adventurous audience and a really younger one. That’s why it’s always been possible to make those theatrical experiments,” says Whyman. “It’s had very strong waves throughout its history of trying to get ahead of what we think of a changing world. So rather than being a place that does commentary or issue plays, it has a strong philosophical sense of being a space where we can think about the big questions.”

This is especially apparent under McDougall and her predecessor Haydon, whose work has been an ongoing interrogation of how we live now, the stories we tell and the connections we make with each other across the world.

Manifesto for change

As part of the current 40th-anniversary celebrations, McDougall and the Gate team have created a manifesto for the theatre. It states that process and form are both political, that the work made at the Gate doesn’t want to just portray the world but actively to change it. “What happens after the play is the point of the play,” it declares.

The intimate nature of the venue means there is no getting away from the fact that audience and actors are in a shared space together. Theatre there is always a conversation, not a one-sided debate. As actor Thalissa Teixeira, who appeared at the Gate in The Unknown Island and Dear Elizabeth, says: “It’s a communal experience. It’s terrifying as an actor because there is absolutely nowhere to hide. But it feels as if you are genuinely sharing something, that actors and audience are all in it together, and it makes you more direct and honest. There is no room for the extra fluff that often gets added in other theatres for the sake of spectacle.”

But if the Gate is a place of opportunity that can be exposing and expose dishonesty, it also sometimes been a haven, a safer place to take risks. In the wake of the furore over Blasted at London’s Royal Court in 1995, Sarah Kane worked on two productions at the Notting Hill venue: writing and directing Phaedra’s Love in 1996 and staging Buchner’s Woyzeck the following year.

Linton, now artistic director at the Bush, who worked as an assistant and subsequently associate director at the Gate, says the experience enabled her to make the leap to working full-time in theatre, but most importantly it made her feel that it was a safe place to discover the extent of her own ignorance, learn how a theatre is run and spread her creative wings.

“Everyone talks about the space, but the core of the ethos of the Gate is not actually the building; it’s the people who work there, the fact it sees itself as a place to learn and teach yourself and that you are fully supported in doing that. As a young director, that makes you feel safe and that makes you brave.”

Looking ahead

Linton’s affirmation that the Gate’s ethos is not the space but those who work there, and the baton that is passed from one generation to the next, is crucial as it contemplates its future.

For the past 40 years the Gate has repeatedly proved its bravery, but coming so late to the portfolio it has been underfunded and playing catch-up ever since. But it also faces substantial challenges if it is going to continue for the next decade, let alone the next 40 years.

It is a conversation that has been live since Abrahami and Cracknell’s tenure, but under McDougall the issue is more urgent than ever, and she and her team are confronting the dilemma head on. Quite simply the issue is this: if the Gate is going to survive and be fit for purpose, it is going to have to move from its current home. Should it stay or should it go?

“It is impossible to make our current space physically accessible and financially sustainable. It is simply not acceptable that the Gate is inaccessible to some audiences. It’s not financially sustainable because of its size, and we don’t have the rehearsal room or the bar that give financial ballast to other theatres. We have always been a hand-to-mouth organisation, but austerity and Brexit are making it harder and harder to keep going. We have to resolve this, but of course looking for spaces in west London is like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

There will of course be those who argue, just as the arguments were made over the decision to seek core funding, that the magic will be lost if it departs the building where it began. But if the Gate is so much more than its space, if it is an ethos, a network and a state of mind, a spirit, then that will continue wherever it is physically located. If it is a more hospitable place for those who work and see shows there, that can only be a bonus.

Of course, the Gate will change if it moves, but the magic of the place is embodied in the principles of the work, which is playful, experimental, global and useful. Those who cherish the Gate and the nights spent there will still have their memories. What seems only right is that future generations of Gate artists and audiences should get the chance to make their own.

Long Reads

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99