Tim Bano

Tim BanoTim Bano is an award-winning arts journalist who has also written for the Guardian and Time Out, and worked as a producer on BBC Radio 4. ...full bio

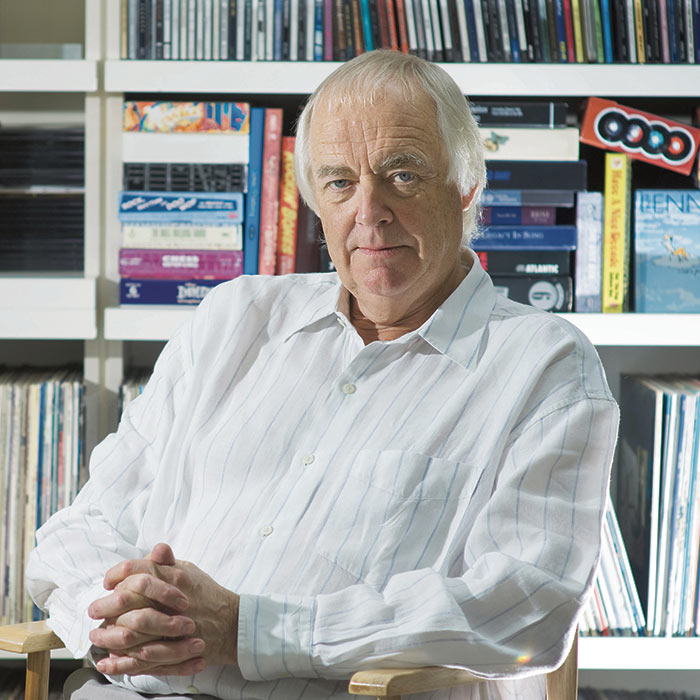

The world-famous lyricist behind Evita, Jesus Christ Superstar and Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, Tim Rice tells Tim Bano about starting out in pop music, working with Disney and Andrew Lloyd Webber, and why he thinks From Here to Eternity – of which a revival is opening at Charing Cross Theatre this week – was a flop the first time around

“Here I have a lovely parrot sound in wind and limb. I can guarantee that there is nothing wrong with him.”

Those words, strange as they may seem, hold an important place in the history of musical theatre. They were the first lyrics a floppy-haired, reluctant young legal clerk wrote for a floppy-haired, ambitious young organist’s son in the spring of 1965.

The words introduce a song that forms part of a musical about the philanthropist Thomas Barnardo, and those two optimistic lads, who had met only a few weeks earlier, were convinced that their show would take the West End, maybe the world, by storm.

It didn’t. In fact, it took 40 years before The Likes of Us was produced, and even then it was at a private festival on the estate of a certain Andrew Lloyd Webber, who just happened to be the show’s composer.

Those momentous lyrics were the effort of a man whose name, for a long time, was always uttered in the same breath as that composer’s. The inextricability of Tim Rice from Lloyd Webber, even all these years later, is hardly surprising given the way the duo reinvented British musical theatre with three shows that are always on somewhere, whether in “moose-droppings Arkansas”, as Rice puts it, or at the London Palladium.

Only a few days before we meet, for instance, Rice saw a version of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat in Helston, Cornwall, he explains as we tackle some outsized croissants in a noisy hotel bar in Belgravia.

“I got a note from the Helston Amateur Dramatic Society. I get a lot of letters like that and I do what I can to help. Sometimes I’ll send a video message. But I have a house near there, so I went along. It was pretty good.”

It’s the sort of thing that the genial, self-effacing Rice does, in between writing charming letters (he once replied wittily to a review I’d written of Joseph) and watching the cricket.

All very understated from the man whose impact on musical theatre is hard to overstate, particularly with the Lloyd Webber/Rice trifecta of Joseph, Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita, whose creation stories have become so mythologised that someone should make a musical about them.

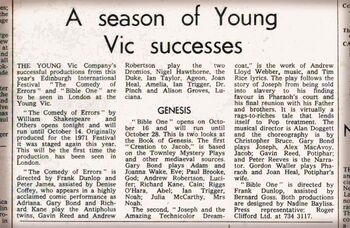

So when, back in 2013, there were two things stirring in the West End, people got excited. Two big musicals, big money, and two very big names: Lloyd Webber and Rice, this time not working together but going head to head. Lloyd Webber’s new musical Stephen Ward was set to open less than two months after From Here to Eternity, Rice’s first new work for 13 years.

‘Normally I get crap reviews and mega-hits. With From Here to Eternity, I was getting great reviews and it didn’t work’

As it was, they both closed on the same day after just a few months. Rice admits it was a flop. “Investors lost their shirts,” he says. He blames the fact that he didn’t try it out-of-town first, and that he was stubborn about it staying in a large theatre, the 1,400-seat Shaftesbury, unwilling to accept that it could thrive in an intimate space. Almost a decade later, an intimate space is what it will have. At the end of October the show opens at London’s 265-seat Charing Cross Theatre.

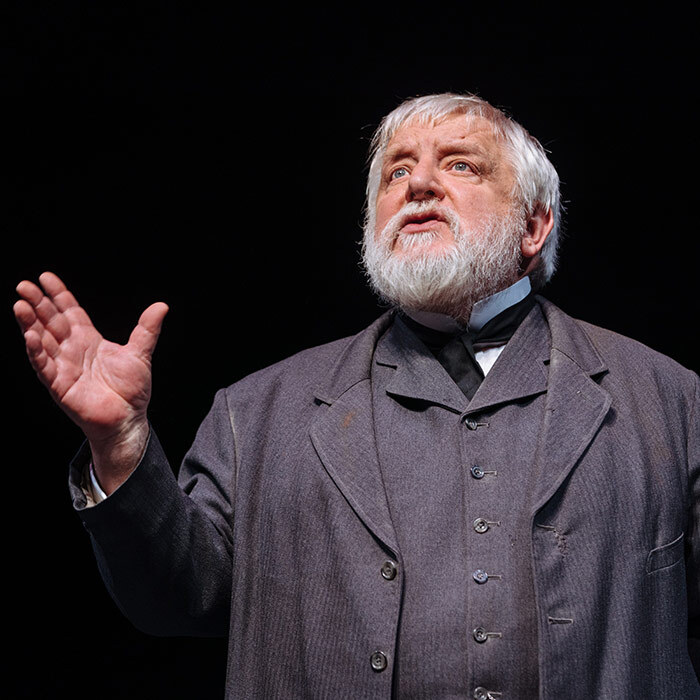

The show is based on the book by James Jones, written in 1951 and set in a US army base in Hawaii just before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although there was a famous 1953 film directed by Fred Zinnemann and featuring an extraordinary cast including Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift, Frank Sinatra, Deborah Kerr and Donna Reed, Rice was the musical’s big draw (although, as Variety’s review of the 2013 production pointed out: “When was the last time anyone booked a ticket on the basis of a lyricist?”).

The show’s composer, on the other hand, was a complete unknown. The story of how Rice met Stuart Brayson is rather sweet. “It was some time in the 1980s, he came bounding up to me in the street aged 18, dressed like someone out of Spandau Ballet. He said: ‘Are you Tim Rice?’ I gave some cheap gag like: ‘Are you buying or selling?’. He said: ‘Listen to this’ and handed me a cassette. I thought he seemed an interesting character and, although I do get sent a lot of stuff, I had a rather flash car at the time which had a cassette player, so I put these songs on and I thought they were rather good. A couple of them had great melodies. So I got in touch and said I quite liked it.”

Rice made a couple of records for Brayson’s band Pop, but nothing came of them. Over the years, though, Brayson stayed in touch. Every so often a fully written musical would arrive on Rice’s doorstep, nine or 10 in total – “one on Byron, one on miners, one set in space” – but the first one that really piqued Rice’s interest was a musical based on From Here to Eternity.

“I said: ‘This is good, do you have the rights?’, and Stuart said: ‘Rights?’” So nothing happened. Rice kept it in the back of his mind to investigate acquiring the rights, but in the meantime he started a more pressing project, namely working with Disney. “Besides, Stuart was busy writing nine other musicals that week.”

The next few years proved extraordinarily fruitful for Rice. When lyricist Howard Ashman died in 1991 midway through working on Disney’s animated film Aladdin with composer Alan Menken, Rice was brought in to finish the job. A few years later he teamed up with Elton John on The Lion King, also for Disney. There was the Cliff Richard vehicle Heathcliff (“living dull”, wagged one critic), another Menken collaboration (with King David), and two more whipped up with Elton John: the animated film The Road to El Dorado and the stage musical Aida, which 22 years later is still yet to receive its stage premiere in the UK.

All through these wild days, it looked like Eternity would have to wait. But on a trip to LA, Rice happened to make contact with Jones’ daughter Kaylie. Although Brayson’s treatment had been largely based on Zinnemann’s 1953 film, when Rice met Kaylie he discovered that Jones’ original version of the book was full of swearing, gay sex and other bits that had to be cut before it was allowed to be published. The condition for staging the musical was that it would be based on this original, uncut version of the book, rather than the more sanitised film.

That meant heavily reworking Brayson’s creation. “His lyrics didn’t fit the story anymore, so I ended up rewriting virtually everything. We sent around a few demos and there was interest, so we took a punt and opened it in the West End.”

Tamara Harvey directed, the late Darius Campbell Danesh starred, and there was a blaze of publicity as we waited to hear whether Rice and Lloyd Webber, albeit separately, were still masters of the musical form. “Normally I get crap reviews and mega-hits. Now I was getting great reviews and it didn’t work. I’d rather the former.”

Rice reckons the show cost about £5 million, and he realises now that it could have all gone differently. “We made some mistakes. The theatre was too big, we should have gone for a 900-seater because it was selling about 900 each night, but it looked empty. Also we should have done it out of town and got it right. We thought at one point it might break even, but in the end the costs were huge.”

One woman who complained about the swearing that Rice, Brayson and book writer Bill Oakes had reinstated was surprised to receive £150 and an apology from Rice himself. “She said: ‘I came all this way and I don’t want to hear someone effing and blinding all night.’ So I replied and said: ‘I feel really bad about this, don’t tell your friends but here’s your money back.’”

When the London run ended in March 2014, an American director called Brett Smock approached Rice and asked if he could direct a version of the show for the US. “I thought: Hey, Broadway! But no, he meant upstate. Way upstate.”

Smock’s scaled-down revival opened at the Finger Lakes Musical Theatre Festival just west of Syracuse in 2016. “We went out and helped. My son Donald rewrote the script, Stuart and I changed one or two of the songs and it worked. It sold out. We realised you can do it small.”

“I think we found the true heart of the piece,” Donald adds. “Someone would come on at the start of the production and say: ‘This is a show about the military. If there’s anyone here who has served, would you make yourself known because we’d like to show our appreciation?’ You’d always get five or six people standing up, and there would be an instant round of applause. It set the sort of spiritual tone, if that doesn’t sound too ridiculous.”

Smock suggested bringing the show back over to the UK, and it’s this smaller version that opens at the Charing Cross Theatre. So will it succeed this time? “Who knows. Nobody knows anything, that’s one of the great rules,” says Rice. “But it’s got a good story, and story is king. Superstar is a good story, Six is a good story” (Rice is a huge fan of Six). “A lot of musicals and shows seem to be rather introspective. I think you can get far more interest in the human condition, I say pretentiously, by telling a story and seeing how the characters react. I get sent a lot of shows saying, you know: ‘This is about muscular dystrophy.’ It’s a worthy cause, but it doesn’t strike home. It won’t be a big success. The issue will be helped if the story is great.”

From EMI to Evita

In that sense, Rice’s own story isn’t bad fodder for a show. Born in 1944 to parents who met in Palestine during war service and married swiftly in Cairo, he grew up comfortably and attended Lancing College where, incredibly, one of his classmates was called Andrew Webber.

“My parents weren’t particularly musical, in fact I would say they were rather unmusical, but they were very literary. My mother wrote a lot of articles and books. My father was in the aviation business, but he wrote very funny letters, usually complaining about something,” a trait which his son seems to have inherited.

“It’s odd,” says Rice thoughtfully. “The years when I was grooving around EMI records and wondering what’s top of the charts, [at the same age] they were wondering: ‘Will my friends be alive next week?’”

After serving in the army, Rice’s father Hugh then worked for De Havilland Aircraft. “He was a super salesman. He would go out to Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, India and essentially flog aeroplanes.” Rice’s parents spent the last years of their lives in Jordan, a country they loved, and it’s clear that they passed on a deep love of travel to their son.

“For me, the great thrill about doing okay in the theatre business is travelling. If The Lion King comes on in São Paulo and they say would I like to go, I say I’d love to, mainly to see São Paulo. I mean, I’ve seen The Lion King 400 times, and also it’s in Portuguese.” Although, he adds: “If I see one of my shows in another language I can relax because if they get the words wrong I won’t really know. I can listen to the music much more.”

Does he get control over foreign-language translations of his work? “I get sent a copy to approve, but I have no idea what it says. I speak a bit of French and a smattering of German, and I can understand that the translation is saying the right thing, but I don’t really know if it’s Keats or Hallmark greeting card. It’s a strange thing, having the shows going around the world. It’s even stranger because I never wanted to be in the business in the first place.”

The young Rice’s ambitions were set firmly on becoming a rock star. As a teenager he sang in a few bands “not particularly well”, but assumed that life meant “getting a job you didn’t particularly enjoy and getting smashed at the weekend”. So he decided to become a lawyer.

‘If I see one of my shows in another language I can relax because if they get the words wrong I won’t really know’

It was while working as a legal clerk that he met Lloyd Webber. “It seemed strange that he hadn’t thought about getting a proper job. I think meeting Andrew made me realise that I should be doing what I wanted. I was a bit scared of telling my parents, but I eventually confessed to them that I felt I’d failed and I didn’t want to do this job. To their credit, they said: ‘All you ever do in your spare time is collect records. You know more about record companies and pop music than anything else. Why don’t you get a job in the record industry?’”

Rice joined EMI as a management trainee, “essentially an office boy”, which allowed him to see how all the departments worked. “It was a great time to be there. The Beatles, Beach Boys, the Hollies, Cliff Richard. I went to record sessions and learned the business.”

It was the record industry that helped turn British musical theatre on its head. The release of Superstar and Evita as records before their stage incarnations was a revolution. People could buy the recordings, the songs would get traction, and producers could stage the shows knowing there was an appetite for them. It was all rather perfect: Lloyd Webber couldn’t stop writing musicals, but nobody wanted to put them on. Rice knew how to make a record. “My contacts in the record business got us the Joseph record.” They found their template and the rest is history.

From Here to Eternity

We discuss a few of Rice’s other hits, the Bond theme he wrote, the savagery of critics, and Chess – one of the greatest musical scores of all time, which has never really worked on stage. It’s one of Rice’s favourites among his shows.

With Chess, Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus of ABBA wrote some of their best songs, and Rice some of his best lyrics. Take the classic I Know Him So Well: “No one in your life is with you constantly / No one is completely on your side / And though I’d move my world to be with him / Still the gap between us is too wide.” It’s quintessential Rice: plain language, unfussy, gently expressing big emotions and relying on simple rhymes. Conjure the image of Elaine Paige and Barbara Dickson singing those words with all that bouffant hair, and what’s not to like?

But in the course of its almost 40-year life, Chess has never quite found the right way to fit that score together into a coherent production. “We made a mistake by saying on the record that Chess is a work in progress. That made every subsequent director think they could solve it.”

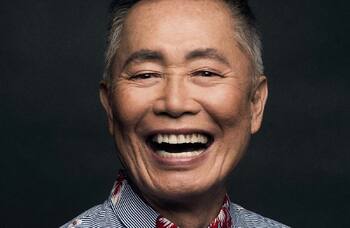

We talk for a long while about Rice’s specially made CD box set containing every demo and scrap of song written, and the difficulty of third-wheeling Benny and Björn’s writing partnership, as well as how Chess would land now. “It’s the right time for Chess for three reasons: one, the renewed tensions with Russia; two, the success of [Netflix series] The Queen’s Gambit; three, I’m getting on,” he says.

Not that Rice shows much sign of it. Chess is receiving a charity concert in the US in December, the form that Rice reckons works best. Aida is tentatively skirting the UK, with a production opening soon in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, he’s been steadily recounting his life story and the histories of his shows in a podcast called Get Onto My Cloud, which he started during lockdown.

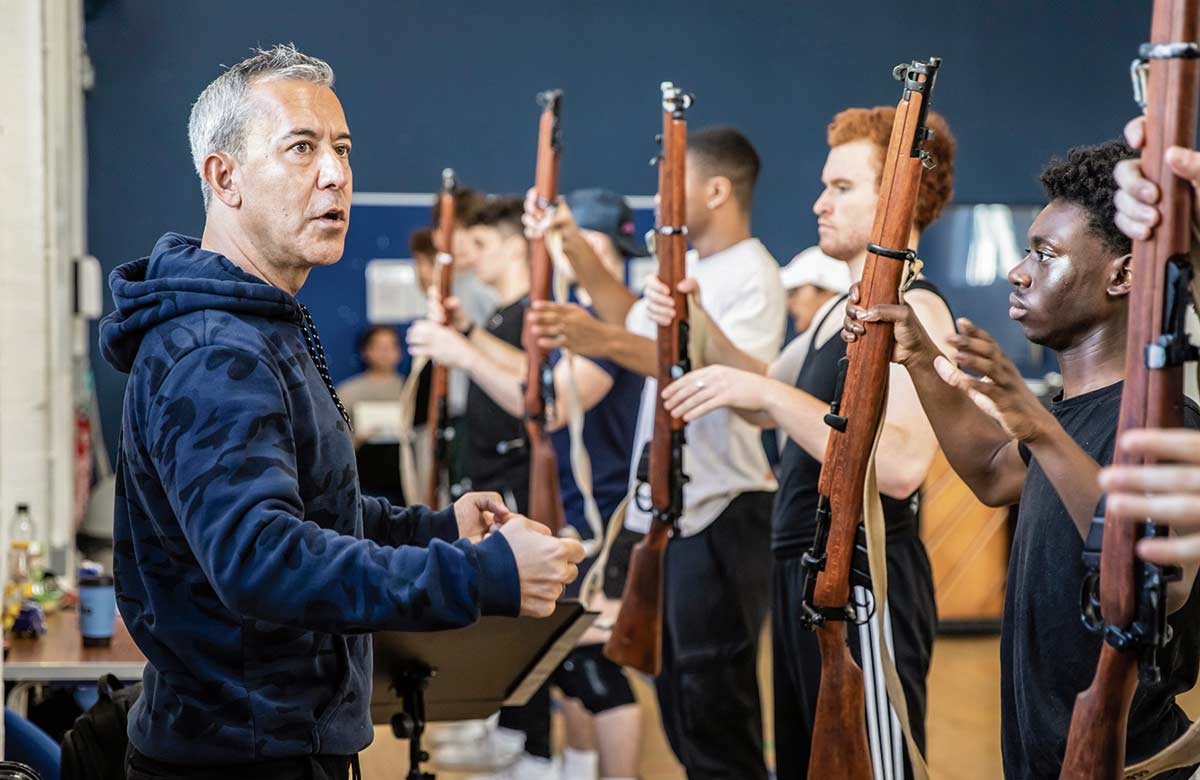

But for now, he’s off to see the first rehearsal of From Here to Eternity. When it opened in October 2013, one critic quipped that it should be called “From Here to November”. Nine years later, Rice is optimistic that, like so many of his creations, its reputation will linger a bit longer.

From Here to Eternity runs at Charing Cross Theatre from October 29-December 17

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99