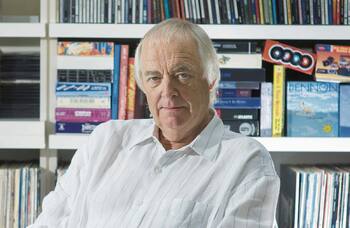

Fergus Morgan

Fergus MorganFergus Morgan is The Stage’s Scotland Correspondent. He has also written for The Scotsman, The Independent, TimeOut, WhatsOnStage, E ...full bio

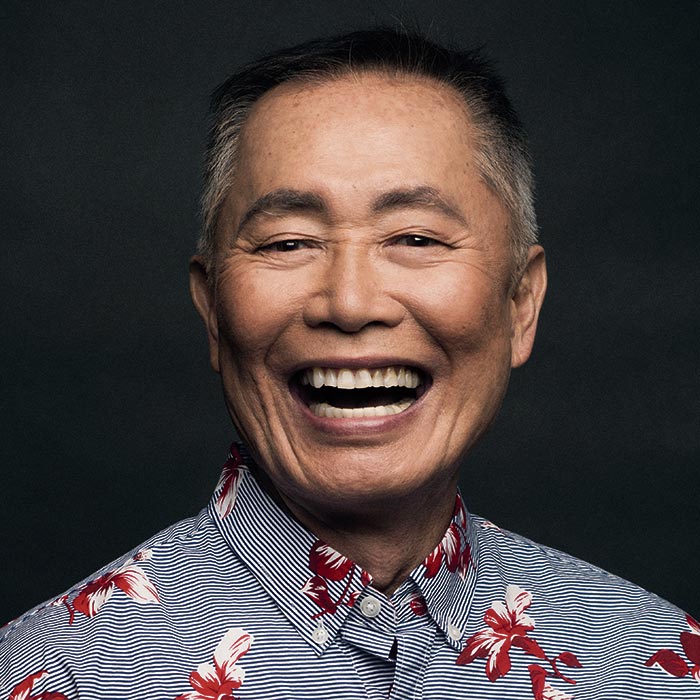

As a child during the Second World War, George Takei and his family lived in an internment camp for Japanese Americans – now his musical about the experience, in which he stars, is coming to Charing Cross Theatre. The Star Trek actor tells Fergus Morgan about working alongside Richard Burton, being a meme and how Arnold Schwarzenegger inadvertently encouraged him to come out

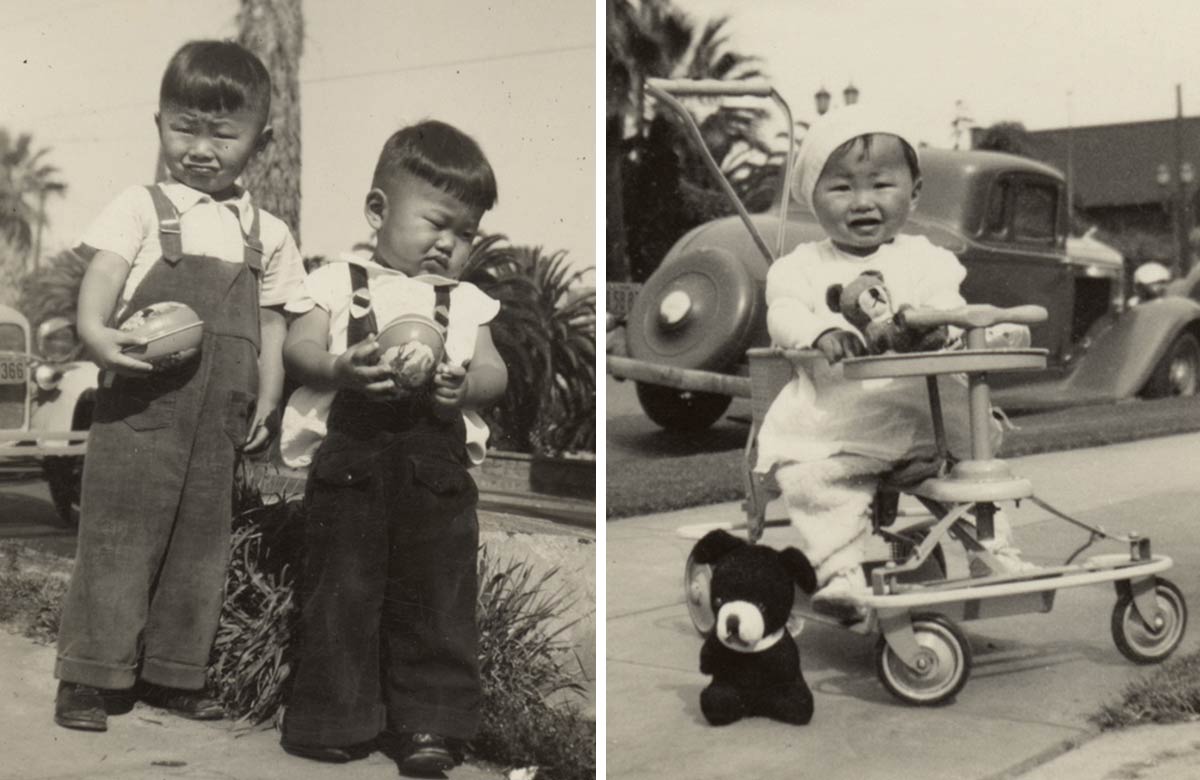

One of 85-year-old actor George Takei’s earliest memories is of looking out of the window of his family home in Los Angeles, California, and seeing two American soldiers marching up the driveway.

“They carried rifles with shiny bayonets on them,” he recalls. “They stomped right up to the porch and started banging on the door. My brother Henry and I froze with terror. My father answered the door, the soldiers pointed the bayonets right at him and said: ‘Get your family out.’”

“My father gave Henry and me two boxes tied with twine,” Takei continues. “He carried two heavy suitcases, and we followed him out to the driveway and stood there waiting for our mother. She was escorted out by a soldier, with our baby sister in one hand and a huge duffel bag in the other, and tears streaming down her cheeks. I remember that morning so vividly. It is seared into my memory.”

It was 1942 and Takei was five. In December 1941, the Japanese Navy Air Service had launched an attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, drawing the US into the Second World War. The following year, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorising the incarceration of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans – including Takei and his family – in camps across the country. In 1982, a US government study found the act was unjustified and based on “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership”, and, in 1988, the US Congress issued a formal apology.

Twenty years later, Takei started creating a musical about the events that followed Executive Order 9066. The resulting show, Allegiance, premiered in San Diego in 2012, opened on Broadway in 2015 and ran in Los Angeles in 2018. It is, Takei explains via Zoom from his London hotel room ahead of the show’s UK premiere, his “legacy project” and it involved him mining his own memories for material.

“We were all categorised as ‘enemy aliens’, even five-year-old me,” Takei remembers. “It was crazy. We weren’t the enemy and we weren’t aliens. We were loyal Americans. My mother was born in Sacramento, California, and my father was a San Franciscan. They met, married and moved to LA, where my siblings and I were born. The only thing that was different was that we looked like this.”

In fact, Takei explains, many of the young Japanese-American men incarcerated under Executive Order 9066 were desperate to fight for their country and many eventually did. The 442nd Infantry Regiment was formed almost entirely of Japanese-American soldiers in 1943, sent to fight in Europe – in Italy, France and Germany – and became the most decorated regiment in US military history.

‘We weren’t the enemy and we weren’t aliens. We were loyal Americans’

Takei and his family were forcibly moved to racehorse stables on the outskirts of Los Angeles, then to a specially built internment camp in Arkansas swamplands, then finally – after Japanese Americans were further segregated through a blunt “loyalty questionnaire” in 1943 – to another camp in northern California. It was scary and confusing, Takei recalls, but simultaneously interesting.

“I was a kid from southern California who suddenly found himself in the swamps of Arkansas,” he says. “The barbed wire fences and the bayou trees, with their roots going in and out of the black, murky water – it was an exotic land for me and my brother. We were fascinated by it all at the time.”

After the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – in which his aunt and cousin were both killed – and the end of the Second World War, Takei and his family were released. They had no home, no bank accounts and no business, and had to rebuild their lives from nothing. It was several years later, when Takei was a teenager, that he started to comprehend what had happened to his family.

“When I was older, I had many after-dinner discussions with my father about democracy and justice, and government and about our imprisonment,” Takei says. “On one occasion, he told me that seeing his two boys play within barbed-wire fences tore him apart. He had so much hope, so much aspiration for his family. That was suddenly taken away from us and that tore him apart.”

To boldly go

Takei is known to millions of sci-fi fans around the world as Sulu, helmsman of the Starship Enterprise in the original three seasons of Star Trek – and in dozens of films, series, animations and video games that followed. He did not train as an actor first, though. After the Second World War, his father built a successful real-estate business, and initially wanted his son to become an architect.

“I liked architecture, so, as a good son, I became an architecture student at Berkeley,” Takei says. “My burning passion was acting, though. When I was in high school, I would go to the theatre in downtown Los Angeles that played all the touring Broadway shows. I made friends with the house manager, Mrs McManus, and said: ‘If I usher for you, can I see the shows for free?’ And she said: ‘Yes, under one condition. You have to wear a suit and tie.’ And so that’s what I did.”

Takei graduated and started working as an architect, but still dreamed of acting. Eventually, his father relented and offered him a deal: Takei could move to New York, try to get into the Actors Studio and pay his own way – or stay in California and his father would subsidise him while he trained as an actor at UCLA. “I was a practical kid,” Takei laughs. “I went to UCLA.”

At UCLA, Takei was spotted by a Warner Bros casting director and offered his first film role – a minor part opposite Richard Burton in the 1960 Alaskan-set movie Ice Palace. The film was not a success – Burton would later label it “a piece of shit” – but it introduced Takei to Hollywood, and to one of his acting idols. Burton’s star was rising – his Tony-winning turn in Camelot would soon follow.

“He was such a charming, engaging, charismatic man,” Takei remembers. “I loved talking to him and I was full of questions. He was still a young man then, and a womaniser. We’d walk back from the set to the hotel, pass by the saloon and these girls would come out. He’d shout: ‘Oh, Isabelle, Annie. How are you girls today? George, I’ll see you later.’ And off he’d go into the saloon without me.”

After Ice Palace, Takei spent several years as a jobbing actor in Los Angeles – providing English voice-overs for Japanese films, as he is fluent in both languages, and performing small roles in films and TV shows – before being offered the life-changing role of Sulu in Star Trek in 1966. He appeared in 51 of the original 79 episodes and the TV show has, to an extent, defined the rest of his life.

It led to six more Star Trek movies and dozens of spin-offs, and made him a permanently popular figure at sci-fi conventions worldwide. It is the platform from which he built his subsequent five-decade career as a performer, personality, writer and activist. And it is the reason why, 53 years later, he still signs off this interview with a Vulcan salute and the farewell: “Live long and prosper.”

The bulk of Takei’s career has taken place on screen – as well as Star Trek, he has featured or cameoed in countless TV shows, from Miami Vice to Murder She Wrote, from The Simpsons to Scrubs, from The Celebrity Apprentice to BoJack Horseman – but his passion for theatre has never waned. He has regularly appeared on stage, often in California, but occasionally elsewhere.

In Los Angeles, Takei has been heavily involved with East West Players, an influential theatre company for Asian-American artists, founded in 1965, whose list of alumni reads like a who’s who of Asian-American acting excellence. Takei played the lead role in Peter Shaffer’s Equus with the company in 2005 and subsequently served as chair of its board of governors for several years.

“When I first started working in film and television, most of the roles open to Asian-American actors were replicating stereotypes, so we had to create our own opportunities,” Takei says. “I never thought I would get the chance to play Martin Dysart in Equus. I saw Anthony Hopkins and Richard Burton – my Richard – do it on Broadway. Leonard Nimoy, my colleague in Star Trek, replaced him. Leonard later came to see me do it in Los Angeles. He told me I did it better than him, which was a massive lie. He was that kind of friend, though. He was so supportive.”

“East West Players was organised to show what Asian-American actors can do, and it has,” Takei continues. “Its original goal was to get Asian-American actors jobs in film and TV, and it succeeded. The next step is to have bankable Asian-American movie stars, like how Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman are bankable African-American movie stars. If names like that are attached to your project, your project gets done. We need that. I have limited time to contribute to that at my age, though.”

Takei is also a self-confessed Anglophile like his father before him – he is named George, in fact, after King George VI, who was crowned shortly after Takei was born – and has worked in theatre on this side of the Atlantic, too. He studied at the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon – a postgraduate present from his father – and performed at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1988.

“I am also one of the few Americans to have appeared in many pantomimes,” Takei adds. “Although I’m always playing either the genie from Aladdin or the emperor of China. They are a hoot, though.”

Becoming an activist

Takei’s career has not just taken place on stage and screen. Since he was young, he has been an energetic political activist, first running for office – as a Democratic candidate for the Los Angeles City Council – in 1973. He lost, but later served on the board of directors of the Southern California Rapid Transit District – a dry-sounding name for an important state agency – and was allegedly called away from a Star Trek set to cast the deciding vote on the creation of the Los Angeles Subway.

In 2005, Takei came out as gay, revealing that he had been in a relationship with his now husband Brad Altman – who helpfully assists him with his schedule of Zoom interviews – for 18 years. The announcement was published in California’s Frontiers magazine and made in anger after then governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed bills that would have legalised same-sex marriage.

“Why did it take me so long to come out?” Takei asks himself. “Because I’m an actor and I wanted to work. I learned at a young age that you couldn’t be an openly gay actor and hope to be employed. And I was already an Asian-American actor, so I was already limited a lot. To this day, there are big Hollywood actors who are not out in order to protect their careers.”

“I was closeted for a long period of my career,” Takei continues. “I was silent during the AIDS crisis, which fills me with guilt, although I did write cheques and cheques to AIDS organisations. Why did I come out when I did? Because Schwarzenegger presented himself as a movie star who had worked and was friends with gays and lesbians, many of whom voted for him, but then vetoed that bill. I was so angry that I spoke to the press for the first time as a gay man at the age of 68.”

‘I learned at a young age that you couldn’t be an openly gay actor and hope to be employed’

Takei has been a prominent advocate for LGBT+ rights, as well as a campaigner for Asian-American actors, ever since. Social media has helped amplify his message: he has 9.5 million followers on Facebook and 3.4 million on Twitter. He has even become a meme. A clip of him saying: “Oh my”, in a deep, surprised voice, originally lifted from a Howard Stern radio interview, proliferates online. “I don’t mind it, no,” Takei says. “Anyway, there is nothing I can do about it now.”

In 1986, Takei was inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame in recognition of his acting career. In 2004, he was inducted into the Japanese Order of the Rising Sun in recognition of his contribution to US-Japan relations. In 2007, he even had an asteroid named after him by the International Astronomical Union. By then, Takei could have considered well-earned retirement, but he still had a story he wanted to tell – the story of his family’s internment during the Second World War.

Q&A George Takei

What was your first non-theatre job?

During summer vacations, my brother and I used to mow lawns for our neighbours.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Ushering in a theatre in downtown Los Angeles. My first professional acting job was dubbing a Japanese sci-fi monster movie. My father found an advert in the paper for that.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Learn from observations.

What’s your best advice?

It is a tough and challenging road to travel – but have confidence in yourself and keep on keeping on.

If you hadn’t been an actor, what would you have been?

Probably an architect – and a good son.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

I’m a Buddhist. I accept the givens in life – learn from your experiences and add that to your wealth of wisdom.

Creating Allegiance

“My husband and I go to the theatre a lot,” Takei explains of the show’s origins. “Once, when we were in New York, we got chatting to two other audience members, an Asian-American guy and an Italian-American guy. The next night, we went to see In the Heights, and the same two guys were there again. They saw I was getting choked up over a scene in which a father is feeling useless, so, when we went for a drink afterwards, I told them about my father and my childhood in the camps.”

One thing led to another and the three of them – Takei, plus composer Jay Kuo and playwright Marc Acito – ended up collaborating to create a musical, heavily inspired by Takei’s memories of his childhood and his research into the events that shaped it. Allegiance, which has music and lyrics by Kuo and a book by Kuo, Acito and Lorenzo Thione, premiered in San Diego in September 2012, before transferring to Broadway in 2015, and playing LA three years after that. Now, 10 years after it was originally staged, the musical is making its UK premiere at London’s Charing Cross Theatre.

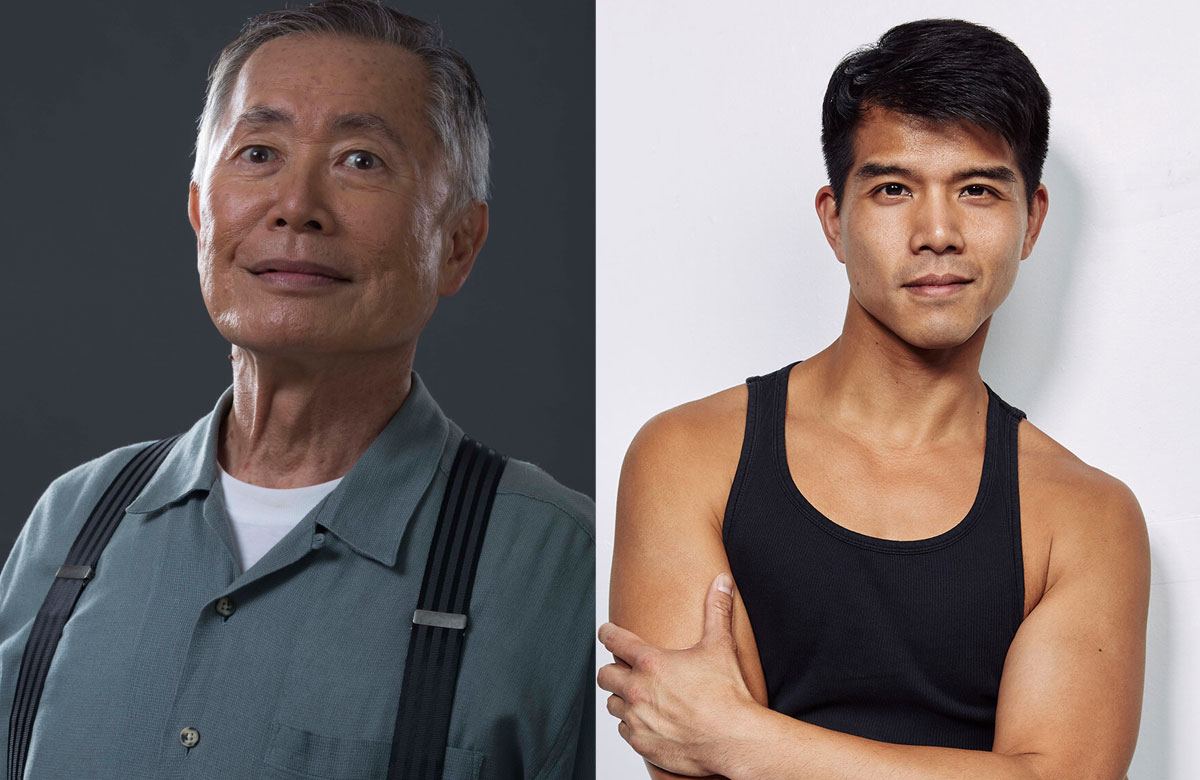

Takei has been with it every step of the way, and performs as both Ojii-chan, the paterfamilias of a Japanese-American family torn apart by Executive Order 9066 and the ensuing events, and as an older, present-day version of Ojii-chan’s grandson and the musical’s protagonist Sam. American musical-theatre star Telly Leung stayed with the show from San Diego to Broadway as well, and will also reprise his performance as Sam in London.

Did Takei have any qualms about revisiting the show at 85? “Of course not,” he replies. “I’m an actor. Before this round of promotion for Allegiance, I did a guest spot in a TV comedy called Call Me Kat. Then, all these interviews. Then, I’ll be rehearsing for the show again. I’m still a working actor.”

Takei remains motivated by his desire to share his story and to raise awareness of the treatment of Japanese-Americans during the Second World War. As well as creating Allegiance, he wrote about it extensively in his celebrated 1994 memoir To the Stars, spoke about it during a 2014 TED Talk, and explored it again in his award-winning 2019 graphic autobiography, They Called Us Enemy, co-written with Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott, which has illustrations by Harmony Becker.

“My mission in life is to get this chapter of American history known to Americans,” Takei says. “To this day, there are so many Americans who don’t know this story, and it is still so relevant to what is happening. We are now reaching another level of honesty in examining American history, and Allegiance is part of that movement.”

CV George Takei

Born: Los Angeles, 1937

Training: MA Theatre, UCLA

Landmark productions:

• Equus, East West Players (2005)

• Allegiance, Old Globe Theatre, San Diego (2012), Longacre Theatre, Broadway (2015), East West Players, Los Angeles (2018)

Allegiance runs at Charing Cross Theatre until April 8. For more information: allegiancemusical.com

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99