Scene Partners review

Dianne Wiest stars in this confusing story of reinvention

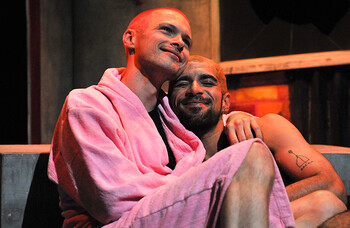

After her abusive husband dies, Meryl Kowalski finally becomes the main character in her own life. But is this new starring role a dream, a hallucination, a delusion, a movie or a little of all these things? John J Caswell Jr’s boundary-breaking play revels in this constantly shifting terrain. However, as it whiplashes in tone from trauma to celluloid dreams, director Rachel Chavkin’s production struggles to tame the shape-shifting material.

Before her dead husband is even in the ground, Meryl (Dianne Wiest) walks away from her home and her adult daughter Flora (Kristen Sieh) and heads west to Hollywood. She gets signed to an agent (Josh Hamilton) by threatening him with a gun and then enrols in an acting class with an over-the-top Australian, Hugo (Hamilton again). When her half-sister (Johanna Day) insists she see a doctor to help her discriminate between fact and fiction, she insists that Hugo has decided to make a movie of her life. Or is all of this just happening in her head?

The fantastical material is not quite heightened enough, leaving us confused and uneasy. Against her will, Meryl has been pretending, playing roles, just to survive. Now, she is creating a world for herself where she can finally be seen. But whether this is due to a head injury, some other illness or rooted in any truth, we do not know. The slipperiness makes it harder to cheer for her reinvention, happiness or self-discovery.

Wiest has a delicate fragility that serves Meryl in her darker moments, but she seems ill at ease with the comedy, appearing hesitant with the physical gags. Hamilton’s roles are colourful caricatures, and he gleefully plays them with bold exaggeration. Eric Berryman, as a cheery doctor who may or may not be real, is a peppy delight.

Alongside the direction, the design by Riccardo Hernández does not help elucidate the play’s murky intentions, with an overly busy visual landscape. Since Meryl dreams of film stardom, the production uses cinematic language, with movie footage, film-noir lighting and familiar movie-credit music. Large screens criss-cross the stage to create cinematic wipes. Sometimes this is exaggerated for comic effect; strolling into Hollywood with vintage footage scrolling behind her, Meryl steps in poop and we screech to a halt and back to some unglamorous version of her reality. At such moments, we can imagine we are in Meryl’s fantasy; other sequences are less clear.

Ambiguity can be its own artistic reward. Here, though, it only makes us wonder what we should feel for this woman and her struggles.

More Reviews

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99