Nora: A Doll’s House review

Innovative revival that, despite an admirable effort, can’t improve on Ibsen’s timeless original

Writer Stef Smith deserves kudos for putting such a fresh spin on Henrik Ibsen’s much-staged masterwork. As the title Nora: A Doll’s House suggests, Smith’s innovative reworking – first performed at Glasgow’s Tramway in 2019 – puts Ibsen’s ahead-of-her-time heroine front and centre, dividing her story between three women whose lives unfold 50 years apart.

Sensibly, other than adding a Sapphic element to the relationship between Nora and the old friend she reconnects with who helps her come to her realisation, the mechanics of Ibsen’s peerlessly constructed plot – which moves along with all the propulsive power of a thrilling film noir – remain largely intact.

Having the story unfurl simultaneously in 1918, 1968 and 2018 could be a recipe for confusion. But, as directed by the Exchange’s joint artistic director Bryony Shanahan, this production never loses its sense of time and place. Even when the central trio of Noras are all onstage at the same time – in scenes fluidly coordinated by Shanahan and movement director Rakhee Sharma – or alternating as Nora’s friend and confidante Christine, the audience never loses track of what’s happening when or who is interacting with whom.

Some of these more histrionic scenes border on the melodramatic, but the cast are never less than convincing. Kirsty Rider stands out most by imbuing her 1900s Nora with a quietly dignified steely resolve.

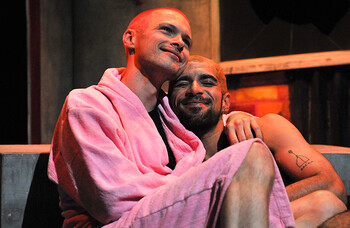

Often at the centre of the whirling action, William Ash manages to make each version of Nora’s gently undermining and domineering husband Thomas subtly distinct, maintaining a consistent core of callousness without tipping him into two-dimensional villainy. And, despite a limited stage time, Naeem Hayat makes a real impact with a restrained, unshowy performance as the lovelorn, unfulfilled local chemist Daniel.

In the middle of the Royal Exchange’s open, in-the-round auditorium, designer Amanda Stoodley’s unobtrusive, star-shaped set struggles to adequately convey the stifling nature of the play’s domestic setting. There’s no iconic door slam to signify Nora’s final departure, but the slowly rotating set, which pulls threads together into a constrictive cat’s cradle that snaps and falls in tatters around the body of a prone Thomas, provides almost as effective an ending.

Splitting up Nora’s story slightly dilutes its impact, despite the way it allows points to be made about the fact the lot of the average woman hasn’t changed all that much in the almost 150 years since the play was first produced. This point is driven home with a climatic, rabble-rousing call to arms, one of many monologue-like sections of narration delivered by the Noras that punctuate the action. It’s another interesting stylistic choice that feels a little too artificial and heightened to really connect, and a misstep when you consider that the original playwright is hailed as one of the godfathers of realism.

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99