Mother Play: A Play in Five Evictions review

Jessica Lange is toxic and glamorous in this uneven new play by Paula Vogel

Dancing cockroaches, a PFLAG field trip to a disco, and a lot of martinis illustrate the landscape of Paula Vogel’s semi-autobiographical drama, making its debut on Broadway. Directed by Tina Landau with colourful panache, the play addresses familial homophobia, gendered expectations and the withholding of a mother’s love. While Jessica Lange gobbles up the meaty role of Mother and tragic experiences befall the family, the play resolves with eye-rolling sentimentalism.

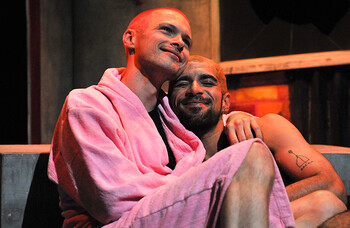

It’s a memory play in which Martha (Celia Keenan-Bolger) tells us a peripatetic tale of apartment moves and evictions with her overbearing mother, Phyllis (Jessica Lange) and doting older brother, Carl (Jim Parsons). The play rapidly covers more than 50 years, from teenage to adulthood – from being abandoned by their father to the evolution of their struggles with their mother. Adults Keenan-Bolger and Parsons bring a convincing, youthful physicality to the roles as teens. As gay siblings who recognise each other’s secret, they share a warm rapport, communicating through a conspiratorial closeness.

But Keenan-Bolger lacks gravitas when she is the adult Martha working through her anger, and ends up a frustrating arms-length narrator. Parsons revels in Carl’s dramatic storytelling and larger-than-life personality, and ages nicely into a more complex adult, desperate for his mother’s support.

Continues...

Lange exudes a timeless glamour that is fitting for Phyllis. Always elegant and impeccably dressed, even for a funeral, she chides her kids on their diction and presentation. Lange reveals both the vivacious Phyllis and five-martinis toxic Phyllis who is doing lifelong damage to her kids. She has the range to do this showier work, including an emotionally freeing dance to Disco Inferno with Carl. Then we watch her scarring them in real time as she venomously articulates all her regrets – though an extended sequence, intended to demonstrate how Phyllis copes with the emptiness of her life and fidgets around her apartment in small detail, lacks impact.

With a set made up of 1960s furniture, vintage glass ceiling lights and Chanel suits or a DVF wrap-dress for Phyllis’ costumes, we get a clear impression of the period setting. The furniture in the apartment is on wheeled platforms that get reconfigured and shifted around by the cast in a smart nod to the packing and unpacking of all the moves, even if a neon stage-framing effect seems incongruous.

Vogel’s play has some zingers for Carl, and more levity comes from visual gags, among them video designer Shawn Duan’s projections of cha-cha-ing cockroaches or the seemingly infinite items that their mother can pull from her purse. The humour is welcome, considering the heaviness of the material; but the spectacle is inconsistently used, so that it ultimately feels tacked on to this sometimes puzzling universe.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99