Hedda Gabler

Hedda Gabler is one of those roles: she is slippery and difficult, brilliant and appalling; she digs her own holes with her own hands and revels in the digging.

Following the London run of his production of the David Bowie musical, Lazarus, Ivo van Hove makes his National Theatre debut directing Ruth Wilson in the role. Wilson’s Hedda is poised and compelling. There’s a faint air of head girl petulance to her manner underscored with something more unsettling. She’s a bully. She’s a manipulator, who takes pleasure in breaking things, including people, but for all this she’s still oddly voiceless, her frustrations and unhappiness repeatedly dismissed.

The things she craves have not come her way. It was time, she says flatly, when asked why she entered into a marriage with Kyle Soller’s Tesman, a man who clearly bores her to tears. “It was time to settle, so I settled.”

Wilson is dressed throughout in a cream silk chemise, the fabric clinging to every curve. It is both seductive and exposing, barely clothing at all. Hands and eyes – her husband’s, his aunt’s – are forever creeping towards her belly

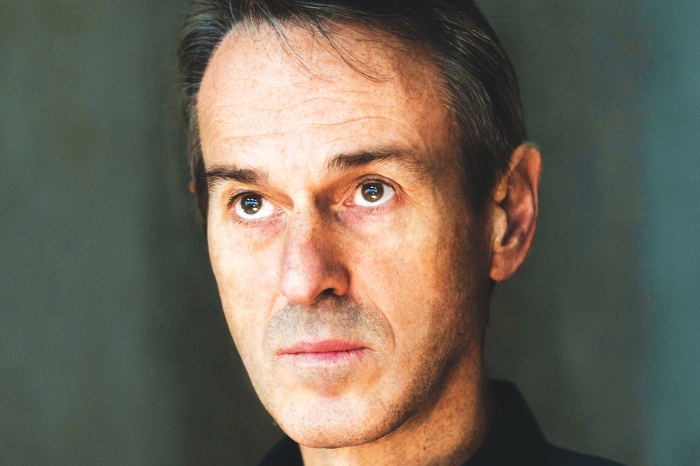

Patrick Marber’s new version of the text encompasses power and privilege: in Marber’s adaptation Hedda cannot see what she has, only what she lacks. As is customary with Van Hove the direction is meticulous. There is an almost hypnotic rhythm to the delivery, though there are times when this leads to the dialogue feeling cold and clinical.

When Hedda levels one of her pistols out into the black the tension is such that it feels as if the whole auditorium is holding its breath. But her angry scattering and stapling of flowers around the stage feels a bit heavy-handed, and the repeated playing of Joni Mitchell’s Blue is also rather on-the-nose.

Jan Versweyveld, Van Hove’s regular designer, has placed Hedda in a raw, plasterboard box – the shell of Tesman’s new and prohibitively expensive apartment. There is something oppressive in its plainness and while it has a window, through which white light floods in, there is no door; characters come and go via the exits in the stalls but Hedda has nowhere to go. A fire grate in the floor lends the burning of Lovborg’s manuscript the air of a ritual.

Kyle Soller is a puppyish and appealing Tesman, an agreeable young academic, though Chukwudi Iwuji a little too collected as Lovborg. Monologues are delivered face-forwards to the audience and a coolness of tone pervades.

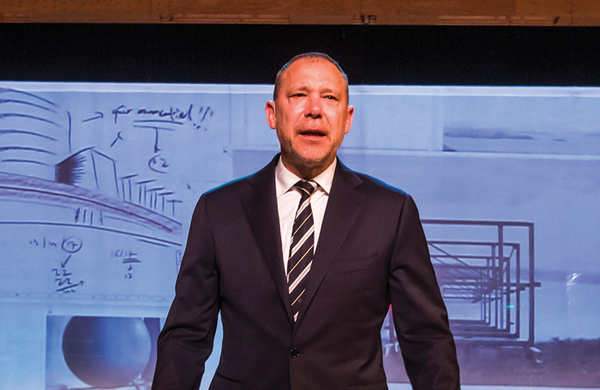

Rafe Spall is particularly unnerving as Brack. Charismatic, confident (and sexually flexible it seems), when he spies the opportunity to get his hooks into Hedda he morphs into a monster. All Van Hove productions contain at least one incredibly striking image: here it’s of Hedda prone on the floor, stained, beneath Brack.

Even if this is meant to illustrate the impossibility of her situation, her relative powerlessness, it’s still jarring and nasty. It sours the whole show. And I’m getting fed up of it. I’m fed up of watching women being violated, fed up of watching them being humiliated even if it is to demonstrate that women’s bodies are never completely their own. In productions directed by men. Turn the page.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99