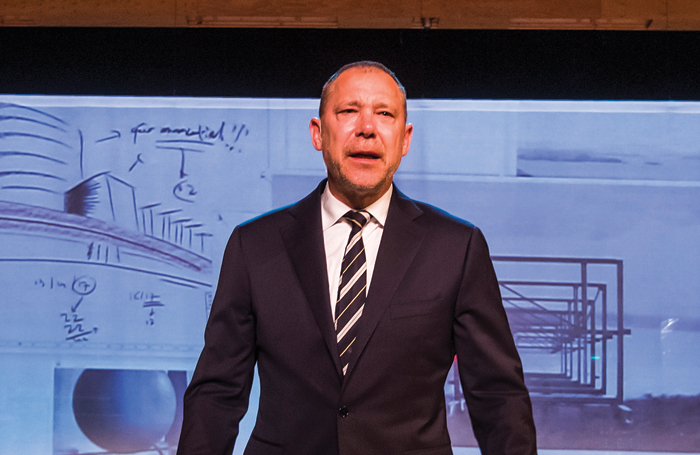

Dutch actor Hans Kesting: ‘The longer I play successful shows, the more nervous I get’

From Othello to Oedipus via Richard III, Dutch actor Hans Kesting has played some of the biggest roles in theatre. He tells Matt Trueman about his 30-year history with Ivo van Hove and how acting helps him stay in control

No stage image has seared itself into my mind this decade, like Hans Kesting sat alone as Richard III, silhouetted by screens, at the end of Kings of War – Ivo van Hove’s history cycle. Barricaded into his bunker, as bodies piled up outside, he clung to power as a metronome ticked off the last minutes of his despotic reign.

For so long, he had seemed a mere buffoon: a lolloping dimwit with a slack-jawed smile, bursting out of his blazer like a schoolboy. He moped at his reflection, a birthmark purpling his face, and played pretend president down an unanswered phone: “Hello Barack,” he’d croon. Even as he lopped off his rivals, one by one, there was no taking him seriously – not until it was already too late.

Kings of War came to the Barbican in April 2016, two months before Britain voted for Brexit, seven before the US voted for Trump. This was a Richard III to make the blood run cold. Three years on, it’s more chilling still.

As more of Van Hove’s shows have transferred to these shores, so Kesting has become a recognisable feature. There’s no missing him, in fact. From his searing Mark Antony in Roman Tragedies, discarding his eulogy script to speak from the heart, to his whirlwind media tycoon in The Fountainhead earlier this month, Kesting is capable of making a mark. He’s a depth charge of an actor, a pressure-drop performer who can single-handedly change the temperature of a show. “I try my best to make things credible,” he says over Skype, sat in the artistic director’s office in Amsterdam. “And I try to be as intense as I can. That’s what I do”. Think of him, perhaps, as Toneelgroep’s talisman.

Ivo van Hove’s Kings of War review at the Barbican Theatre, London

It’s little wonder, then, that when Robert Icke went to work with the group two years ago, the British director chose to cast Kesting as his lead. His Oedipus comes to the Edinburgh International Festival this month: a contemporary adaptation of an ancient tragedy. “I said to him: ‘Why did you write a new version when Sophocles did it so well?’”

Kesting’s Oedipus is a modern political leader: a man on the campaign trail, staving off crisis after crisis. He comes home to his wife and family. “He ends broken,” says Kesting. “I come in like a winner, 100% sure of myself and I end a wreck. It situates Oedipus in the political arena, but what’s important is the downfall of the character.” He remembers an Oedipus from his youth: “I was stuck to my chair: ‘Don’t go there. Don’t ask that. You don’t want to know.’ I just found it so terrible at the end.”

Getting there takes heft, but today, dressed in entirely in baby blue – shorts and short sleeves – Kesting seems slighter than he is on stage; so much so, I wonder if he has a trick to bulk himself up or increase his density. It may be his stillness. He talks 13 to the dozen and fidgets in his seat. “I have a very busy mind, like a carnival of thoughts,” he says. “The thing I love about acting is that it puts me in a different zone. If I’m on, I’ve no problem with things in my daily life, whether extreme fear of death or getting older. It’s not therapeutic, but it grounds me. I’m in control.”

The way he tells it, Kesting’s career has been a search for that control. Born into a “very normal, working-class family” in Rotterdam in 1960 – his father an early computer salesman, his mother a housewife – Kesting was “a bit of a naughty student” who staged his own shows – “Of course, I gave myself the lead.” He fell for theatre on trips with his grandmother – “I drank everything in” – and nurses memories of delivering bread to the city’s theatre and sneaking on stage. “My God to be standing there,” he sighs. “It was so exciting. I always wanted it.”

After training at Maastricht School of Arts, one of three drama schools in the Netherlands, Kesting hit a brick wall. “Everything was a flop. The first five years after that, all my plays flopped. My school time had been so amazing, but coming into the theatre world was a totally different thing. You have to start all over again. I lost all my trust.”

Then Kesting was cast by a contemporary – a young Belgian director who had made waves in Antwerp and taken over a rep theatre in Eindhoven. It started an association that has lasted 30 years. “We just clicked,” he says of Van Hove. “He has a drive and I have that too. Ivo always talks about the Summer Olympics of acting. He wants to make the best possible theatre for the biggest possible audience. The stakes are always high with Ivo – always.”

While both men live through – perhaps even, live for – their work on stage, I suspect they ‘click’ like complementary colours. They are very different sensibilities: Van Hove implacable, poised, considered; Kesting earthier, emotive, instinctive. “We clashed, but they were nice clashes,” Kesting says. “I was 28 and totally unstructured. I was changing every scene again and again. Ivo liked my gusto for trying things out, but at a certain point, he wanted to lock it down. I found that very hard.”

Q&A Hans Kesting

What was your first non-theatre job?

Restaurant dishwasher.

What was your first professional theatre job?

A very bad play. It was to open in a week, an actor was fired, and the boss came to my school to find a replacement.

What’s your next job?

Freud and Who Killed My Father for Toneelgroep Amsterdam.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

You have to give yourself time.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

Ivo van Hove.

If you hadn’t been an actor, what would you have been?

A doctor.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

After every performance, I thank God and my parents. I kiss their engagement picture.

Looking back, Kesting said he became a better actor “by calming down”. He acknowledges key turning points in life: his HIV diagnosis, the death of his parents, a brief stint on television with his own talk show – something he’d always wanted. “It wasn’t my world,” he says. “I felt the weight of the thing on my shoulders. I need an Ivo – someone with vision.”

With Van Hove at Toneelgroep by 2001, the two reconnected. Kesting played Othello to significant acclaim – “You can’t do that now, of course,” he demurs. “I remained white. Whiteness was never the issue” – and, since then, he’s played everything from Roy Cohn in Angels in America to Norman in The Norman Conquests. Toneelgroep suits him, he says. “I’m an ensemble guy and the great thing is that you work fast. There’s no nervousness or shyness. You’re free to rehearse. We know each other. We’re very honest with each other and very quick.”

It has also allowed him to work overseas. “There’s a tendency in the Netherlands to think: ‘Yeah they’ve very good, but we all know that now.’ They get bored for some reason.” Touring internally kicks Toneelgroep on their toes. “It gives you a whole new kick to show your work to a new audience.” It ups the stakes. “The longer I play successful shows, the more nervous I get. I focus too much on the imperfections.”

Does acting cost him? “It takes a toll – not because I, Hans Kesting, go down the drain. I don’t come back to my dressing room and say: ‘Away Othello, come back Hans.’ But it does something to you: these big emotions, these big stories, the intensity with which Ivo plays them – I like that. It gets under your skin.”

CV Hans Kesting

Born: Rotterdam, 1960

Landmark productions:

For Toneelgroep Amsterdam:

• Othello (2003)

• Roman Tragedies (2007)

• Angels in America (2008)

• Kings of War (2015)

• Oresteia (2017)

Awards:

• Louis d’Or best actor for Angels in America (2008) and Kings of War (2016) and nominated for The Norman Conquests (2005) and Roman Tragedies (2008)

• Bearer of the Albert van Dalsum ring since 2015, passed from one Dutch actor to another

Agent: Suzanne Angevaare, Mover Shaker

Oedipus is at King’s Theatre, Edinburgh as part of the Edinburgh International Festival from August 14-17. Go to: eif.co.uk for more

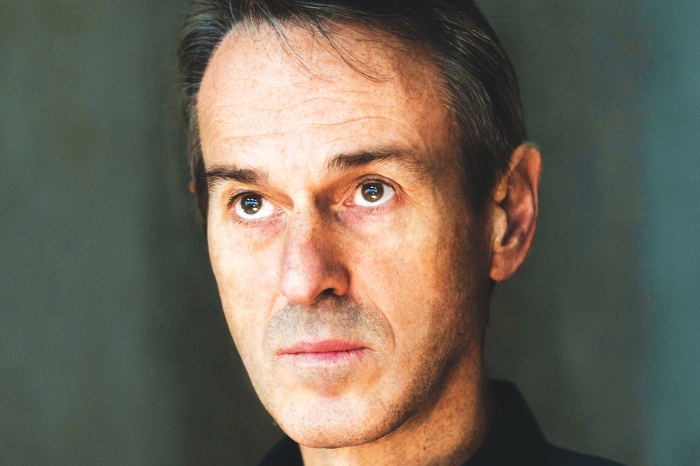

Director Ivo van Hove: ‘I want to make the most extreme art without compromising’

Opinion

More about this venue

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99