Faith, Hope and Charity at the National Theatre, London – review round-up

Alexander Zeldin is the Ken Loach of theatre in the age of austerity. He had a hit in 2014 with Beyond Caring – a play about zero-hour contract cleaners at a meat-packing factory – and another in 2016 with Love, about two families struggling to live in temporary accommodation. He’s now back with the third and final part of a loose state-of-the-nation trilogy.

Faith, Hope and Charity is a play about a struggling community centre with a hole in its roof and developers hovering over it like hawks. It’s directed by Zeldin himself, features a nine-strong ensemble cast, and is running in the Dorfman theatre until mid-October.

Praised, though Zeldin’s previous plays have been, some have accused them of being poverty porn, of holding up poor people’s lives for the educational entertainment of affluent theatre-goers. Others have argued the opposite – that they are instead holding up a much-needed mirror to the effects of Tory cuts.

So, does Faith, Hope and Charity offer another devastating depiction of deprivation? Can the critics sit comfortably in their seats? Does Zeldin tie-up his trilogy with sensitivity and skill?

Fergus Morgan rounds up the reviews.

Faith, Hope and Charity – Beautifully bittersweet

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/19133440/Susan-Lynch-Beth-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-photo-by-Sarah-Lee-100x65.png 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/19133440/Susan-Lynch-Beth-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-photo-by-Sarah-Lee-100x65.png 100w,

Zeldin spent two years researching and writing Faith, Hope and Charity. In it, he depicts an ailing community centre and its visitors who include Hazel, who voluntarily cooks meals for the hungry, Mason, who runs a choir and Beth, who is fighting to keep her child out of care. It is, the critics concur, quietly devastating.

It’s “an utterly necessary and deeply compassionate depiction of the kinds of lives that it is all too easy to ignore,” writes Sarah Crompton (WhatsOnStage, ★★★★), while Dominic Maxwell (Times, ★★★★) calls it “a deeply loving, oddly riveting depiction of people hanging on quietly, but determinedly at the edge of despair”.

Zeldin takes “a similar perspective” to his previous work, describes Laura Barnett (Telegraph, ★★★★), “considering the effects of poverty, marginalisation and our broken social-care system, through a chorus of human stories that take care to show, rather than tell; to persuade, rather than preach.”

“There’s an extraordinary restraint in Zeldin’s writing, much as in his direction, plus a willingness to let time pass and allow silence to saturate the performance gradually, like steady rain soaking through a borrowed jumper,” echoes Dave Fargnoli (The Stage, ★★★★), while Jessie Thompson (Evening Standard, ★★★★) writes that “as a chronicler of the quiet tragedies, small victories and overwhelming mundanities of everyday life, Zeldin remains unparalleled”.

There are a few complaints: Tom Birchenough (ArtsDesk, ★★★) wonders “whether Zeldin has taken his uncompromising naturalism just a step too far”, Crompton points out that some episodes feel “unnecessarily melodramatic”, and Thompson says that there’s occasionally a feeling of “old tricks being recycled”.

But for the most part, the critics agree with Andrzej Lukowski (Time Out, ★★★★). Faith, Hope and Charity is, he writes, “beautifully bittersweet”.

Faith, Hope and Charity – A masterpiece of realism

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/18112433/Cecilia-Noble-Hazel-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-100x65.jpg 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/18112433/Cecilia-Noble-Hazel-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-100x65.jpg 100w,

Zeldin directs as well as writes, with Natasha Jenkins designing the set, Marc Williams on lighting and Cecilia Noble leading a nine-strong cast. The critics have nothing but praise for all of them.

Jenkins’ set is “extraordinary” according to Thompson, and captures a run-down community centre in all its “grimy, utilitarian dinginess” according to Crompton. It is, says Barnett, “a masterpiece of realism”.

There’s admiration for Williams’ lighting as well. “Williams leaves the house lights up almost continually, simultaneously inviting the audience in to the space and confronting us, nakedly, with the injustices we’re witnessing,” writes Fargnoli.

The cast is also on cracking form according to the critics. “The performances are uniformly superb”, commends Crompton, while Lukowski calls them “exemplary” and praises them for “bringing a tremendous depth to characters who always remain resolutely outside of cliché”.

Noble is particularly good. She’s “extraordinary”, says Barnett, “all bustling efficiency and tenderness.” Crompton, meanwhile, calls her “magnificent” and admires how she “manages to show the weariness of Hazel, as well as her goodness, while never suggesting that she is a saint.” She is, comments Thompson, “surely one of our best stage actors”.

Faith, Hope and Charity – Poverty porn?

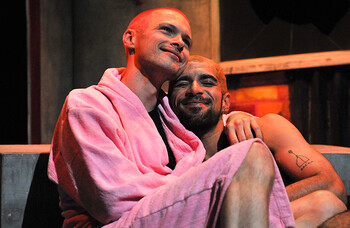

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/19133529/Bobby-Stallwood-Marc-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-100x65.png 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/19133529/Bobby-Stallwood-Marc-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-100x65.png 100w,

Zeldin’s understated play is mightily moving then, and his production of it is blessed by a rivetingly realist design and a set of neatly naturalist performances. But does it stand up on an ethical level? Is it okay to put people’s lives on stage like this?

Some reviews point out a few awkward elements to the show. Crompton confesses herself “uneasy about the fact that every character we fully meet has some kind of psychological difficulty”, adding that “it seems to me that you can need food and company without being traumatised in quite that way”.

Birchenough, meanwhile, doesn’t think that “the slow-burn, almost out-of-time sensitivity” works as well as it did in Zeldin’s previous plays, while Maxwell mentions that “once or twice the play is a bit too conscious in reminding us of how we need to look after each other”.

“The play neither preaches nor hectors,” contends Michael Billington (Guardian, ★★★★). “It simply says that at a time of savage cuts, this is what life is like for many people: it’s a world of food banks, depleted social services and closures of civic amenities.”

“I suppose the fear with Zeldin is that it’s poverty porn,” considers Lukowski. “There is little doubt that we’re seeing fictionalised versions of real lives, presented to us in a plush London theatre where you can drop £50 on a ticket. Is it anthropology, the lives of the poor presented as improving entertainment?”

“Ultimately, I think not,” he answers. “These stories are worth telling because they’re good stories, ones that offer representation for a vast swathe of society that’s usually either untouched or sensationalised by theatre and film.

“I chatted about this briefly to the woman sat next to me, who it turned out was the direct inspiration behind the character of Beth,” he concludes. “She thought it was great, which is good enough for me.”

Faith, Hope and Charity – Is it any good?

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/19133627/Cecilia-Noble-Hazel-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-100x65.png 100w,

d3s3zh7icgjwgd.cloudfront.net/AfcTemp/MediaFiles/2019/09/19133627/Cecilia-Noble-Hazel-in-Faith-Hope-and-Charity-100x65.png 100w,

It’s tough to use qualitative terms about a theatre show that accurately depicts the difficult, desperate lives of some sections in society, but yes, it’s good. Zeldin completes the trilogy that began with Beyond Caring in 2014 and continued with Love in 2016, with another sad, sobering, but sweet, show realistically portraying people driven to the edge by austerity. The play is quietly profound, as are the performances.

Four stars from pretty much everyone suggest that this is a powerful production. If only someone could persuade the prime minister to buy a ticket.

Alexander Zeldin: ‘I want audiences to experience intensity and forget their phones’

More about this organisation

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99