Richard Jordan: Is the art of subtlety being lost in British musicals?

When the curtain came down on Saturday night’s performance of Les Misérables at the Queen’s Theatre, it marked the end of an era. London was the last city presenting the original production, with others around the world having moved to a new version also produced by Cameron Mackintosh.

Going back to watch the original last week, I was struck by how fresh it still felt. This was partly the adaptation and acting performances, but it’s also down to the skill of Trevor Nunn and John Caird’s direction – in particular their staging of its book scenes that regularly use subtle simplicity to punctuate the story.

Frequently, Les Misérables is hailed for its epic staging, but it is the embedded moments of subtlety that truly give the musical its powerful emotional depth and sophistication. The new version of Les Misérables is much broader in delivery, with a greater feeling of flash and awe that’s visually achieved through the use of projection.

This could also be considered reflective of a general gear change within mainstream entertainment, which is often all about being big and loud. TV talent shows that dominate Saturday-night scheduling show their studio audiences constantly giving standing ovations and encouraged to be vocally reactive.

Inevitably, this has crossed over into popular mainstream theatre where at most large-scale musicals, it is now common to see a standing ovation – whether it’s been earned or not – and the atmosphere in the auditorium can be more akin to a concert or watching an episode of The X Factor.

This means that many of these blockbuster musicals are big on the delivery of the songs, but frequently the subtlety of their books is diminished. As a result, real care is needed to ensure that the book doesn’t simply become a series of links between the numbers.

It feels more of a problem within the British commercial musical than its US counterparts. If you look at the majority of the West End’s recent homemade shows, the focus is on revisiting past successes with a heightened focus on ‘entertainment’. In contrast, Broadway is producing an array of impressive new book-driven musicals often dealing with complex subject matters.

There are exceptions: Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole aged 13¾ and Matilda are more recent British musical success stories. But within many British musicals – especially the revised blockbuster – there is much more emphasis on constant action, ensuring audiences keep looking up and not down to check their phones in any of the show’s quieter narrative moments.

There is also a question of whether many British-made musicals are becoming more concert-like in approach. Six is heralded as the most successful and exciting new British musical of the past decade, although effectively it’s an 80-minute concert with a fairly weak book. Later this month, Les Misérables will be staged in a star-led concert version during the Queen’s Theatre refurbishment.

Does this matter? As David Benedict recently highlighted, the book for a musical is its glue and I believe this is the critical key to a musical’s longevity and success.

David Benedict: What makes a good musical? The book, the book, the book

It’s interesting to consider that when Les Misérables, Cats and Miss Saigon all returned to Broadway in revised productions, their runs were comparatively short-lived compared with the original versions. What was missing from them? Maybe their updates were not radical enough, or perhaps they had become brasher experiences and were now missing a level of depth that the original productions better afforded.

However, it may also be down to the increased attention being placed on these shows touring. Once watching a blockbuster musical in the West End was an event, now having it play your local theatre arguably supersedes that.

Many of these UK productions are now being built from the outset with this specific touring focus instead of just a sit-down engagement. This represents a different amortisation of costs that may also lead to a broader approach in their delivery. Often these shows – rightly or wrongly – introduce a ‘Mr Saturday Night’ producing style that may well be reflective of the influence of Simon Cowell (and others like him) over the past two decades on populist British entertainment.

It’s unlikely we will ever see a new commercial West End musical run for 34 years again, but many of these revised 1980s British blockbuster musicals are changing today’s audiences’ expectations of the mainstream commercial musical. Often there is even more attention paid to spectacle and bigger set pieces and less on the show’s subtlety.

Richard Jordan is a producer and regular columnist for The Stage. Read his latest column every Thursday at thestage.co.uk/author/richard-jordan

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

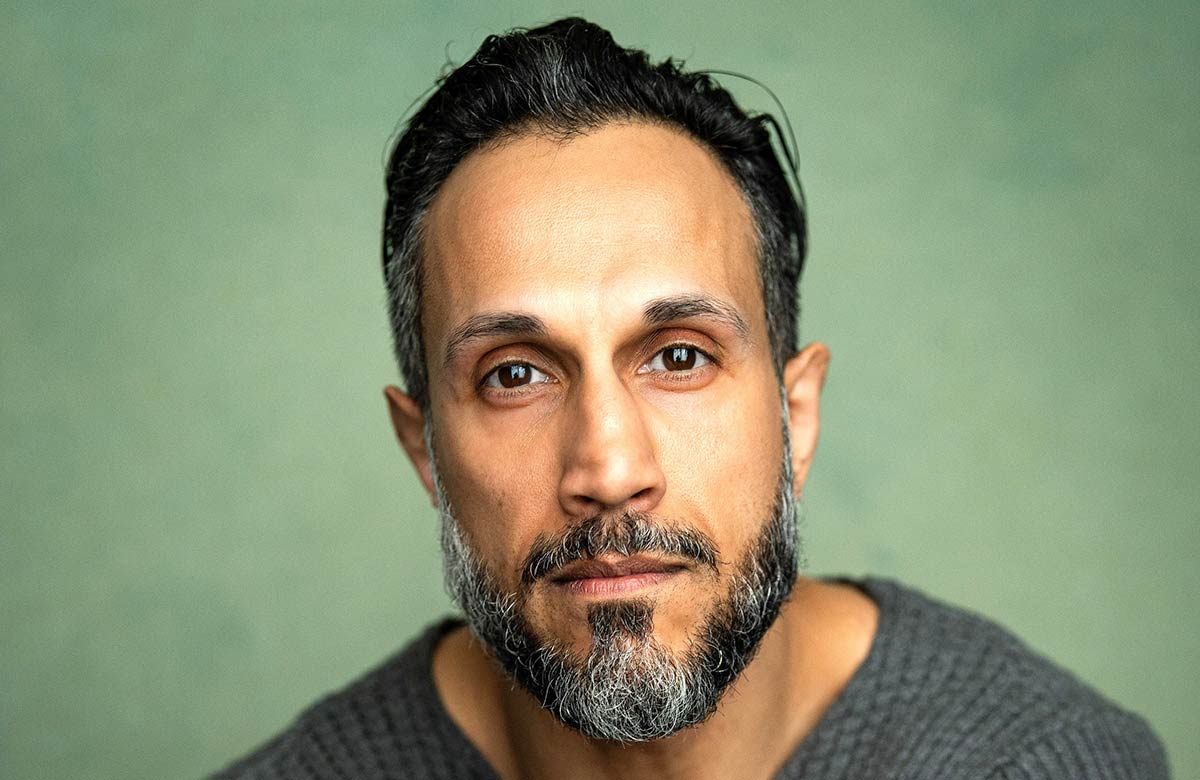

Richard Jordan

Richard Jordan