V&A East: From Ellen Terry's cookbook to Joey from War Horse, the archive opening up theatre's history

As the V&A expands into a new site in east London, Nick Awde speaks to archivists who are hoping that moving its 100-year-old theatre and performance collection will open up the treasure trove to visitors

For a country that boasts theatre as a significant part of its heritage and economy, it’s strange how the UK has historically struggled with the idea of a permanent national theatre museum. But thanks to a pioneering socialite, a unique archive and the London Olympics, staff at the theatre and performance collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum are working on an innovative alternative.

From London’s Olympia to the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, the V&A is planning to bring almost all of its cultural legacy under one roof in east London, in what is the biggest move of its collections since the Second World War. From the end of this year to 2023, more than 250,000 objects, 1,000 archival collections and 350,000 library books will be packed up and moved from Blythe House in Olympia to V&A East, a new purpose-built collections and research centre.

V&A East will have two public venues in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park – a five-storey museum on Stratford Waterfront and a collections and research centre at Here East. Both sites are under construction and will open in 2023 as part of the new cultural hub called East Bank.

Preparing to be part of the move is the team behind the theatre and performance archive. “We are sad to leave Blythe House but this is a fantastic opportunity to become truly accessible,” says head of collections management Ramona Riedzewski, who works as part of a team of 18 people looking after the UK’s national collection for the performing arts.

“At the present building, Blythe House, we have a research room but it has no cafe, no seminar or lunch room for school groups and one public toilet. This building is no longer fit for purpose nor does it meet our visitors’ expectations. A little bit like a dated theatre needing a major upgrade to meet contemporary expectations.”

Situated next to the Olympia London exhibition halls, the V&A archive occupies the former headquarters of the Post Office Savings Bank, built in 1903 – a vast building shared with the British and Science museums. A 30,000 sq metre space, surrounded by Kensington town houses, with only one industrial-strength lift – moving out of Blythe House will resemble a giant game of Tetris with trolleys and trucks.

December 18 is the date when all public access to the old site ceases. When it reopens at V&A East in 2023 under inaugural director Gus Casely-Hayford, the collection will not be a museum per se, but is designed to present the collections in unexpected ways to the public.

5 things you need to know about the V&A’s theatre and performance collections

1. Founded by Gabrielle Enthoven, the 100th anniversary of the collections will be celebrated in 2024.

2. More than 600 archives contain more than 80,000 objects, 100,000 library items and 400 recordings. Currently the museum part is at the Victoria and Albert Museum

in South Kensington.

3. The collections are not just theatre-related but cover all other performing arts forms, including dance, opera, circus, puppetry, comedy, costume, set design, pantomime and popular music.

4. The National Video Archive of Performance was founded in 1992, with live recordings freely accessible in the reading room.

5. The collections close in December 2020, and reopen as part of V&A East in 2023.

“V&A East will work incredibly hard for public access to all of the V&A’s collections,” says Riedzewski. “There will be a central collections hall that can potentially be used as a performance space. We also have a gallery space with a high-level viewing platform to display our backcloth by Natalia Goncharova for Sergei Diaghilev’s 1923 production of The Firebird, which at the moment is rolled up in a crate in a deep store a long way outside London.”

Almost all of the V&A’s collections will be brought together under one roof alongside departments such as conservation, technical services and a digital photography studio.

“All of these are necessary in our day-to-day work,” says Riedzewski, “but we will have the opportunity to open up core activities to visitors, just like the National Theatre has done with its Sherling Walkways at the back of its South Bank building, so people get an idea of real museum life. And perhaps they discover their own interest in some of these highly specialist and skilled roles and will become our future peers.”

As the UK’s national collection for the performing arts, the V&A theatre and performance archive’s remit is to collect the intangible heritage of current and past theatre and performance practice. “Our collections must always have a relevance to the live performing arts in the UK, but it’s such a global art form and industry reflecting the wide range of our materials,” says Riedzewski.

“As an archivist you have to become attuned to the often very different kinds of materials that come, for example, out of the way events such as the Edinburgh Festival Fringe or Glastonbury operate. Trying to capture these performance festivals is a completely different archive challenge in contrast to capturing the Royal Court or Talawa Theatre Company.”

The collection owes its beginnings in 1924 to English socialite Gabrielle Enthoven and her 80,000 playbills. At the time, national theatre collections had been established in the US at the Harvard Library, in Rome, Milan, Stockholm and Paris, but still not in the UK.

Enthoven, who was from a wealthy family and was brought up in India and the Middle East, wrote plays and occasionally performed, but it was her knowledge and passion for the history of theatre that earned her a reputation as the nation’s ‘theatrical encyclopaedia’.

Her vision was to set up a British theatre museum in the 1910s, but after approaching all the major national institutions, nobody wanted her playbills and programmes – or her money. The V&A said no on a number of occasions until finally it accepted her proposal in 1924 following a highly successful exhibition on theatre design in 1922. She immediately brought in her collection and a team of volunteers, financing the department out of her own pocket until her death in 1950 at the age of 81.

‘Our collections must always have a relevance to the live performing arts in the UK’ – Ramona Riedzewski, head of collection management at the V&A

The collection famously got its own building in 1987, Covent Garden’s Theatre Museum, created as a separate institution in 1974. However, lack of funding brought about its closure in 2007. The staff and collections have since been integrated into the V&A, with permanent theatre and performance galleries at its South Kensington museum, and collections consolidated at Blythe House.

After regrouping, the archive has since gone from strength to strength, resulting in a string of top exhibitions such as the Diaghilev and Ballets Russes exhibition in 2010 and David Bowie Is, which opened in 2013 and was on an international tour until the summer of 2019.

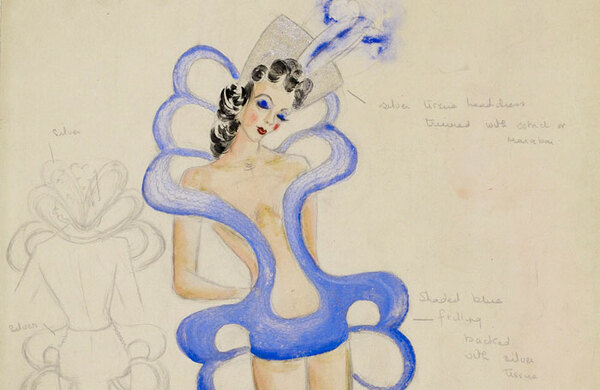

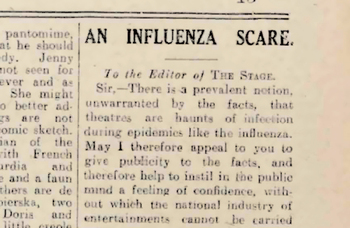

Walking around Blythe House can be a surreal experience. Corridors stretch away to surprisingly light-filled halls over several floors stacked with boxes and costume racks filled with ephemera and treasures. Everywhere there’s a discovery to be found: playbills for the first run of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, Ellen Terry’s cookbook, miscellaneous sequins from the 1920s, lines of leather-bound volumes of The Stage and its rival The Era dating from the 19th century. It also includes the puppet of Joey from the West End transfer of War Horse.

This is a living archive, covering all of the UK’s live performing arts. In between Talawa’s productions old and new, or Frank Matcham’s theatre designs for Buxton Opera House and playbills featuring Ira Aldridge appearing across the UK, visitors will also stumble across a Shirley Bassey dress, a Stefanos Lazaridis-designed set model for Duran Duran’s world tour in 1993 and a Nell Gifford circus painting.

Inside every box is someone’s story waiting to be discovered – a book, play or documentary in the making. And it’s not only relevant for the industry, as Riedzewski points out. “The collections are here for everyone to use, such as the family historian who, for example, wants to know whether a great-grandparent was actually in a D’Oyly Carte original production.

“In fact, during the period when we go dark, we’ll be busy barcoding the archive boxes for the move to the new home, we’ll also be digitising more of the collection and preparing our digital material for the release via the V&A’s online catalogues, so that people can still explore the collections remotely. We have plans in progress to make these amazing collections accessible to everyone. And, of course, we’ll be preparing for our 100th anniversary in 2024.

“There’ll be an Alice in Wonderland summer exhibition at the V&A in 2020 with the theatre performance collections, bringing in theatre designer Tom Piper to work with our lead curator. That’s incredibly exciting because it again brings the community right back into the building,” says Riedzewski.

Until the end of 2020, the archive is running a season of behind the scenes tours and is adding new dates as they sell out. “It’s a good way of piloting for the new home. We want to make sure that everyone knows this collection exists – and that it belongs to everyone.”

vam.ac.uk/whatson; for more information on V&A East go to: vam.ac.uk/info/va-east-project

V&A events to look out for in 2020

- Laughing Matters: State of a Nation, closes March 29, 2021

- V&A Performance Festival 2020, April 23-May 3

- On Point: Royal Academy of Dance at 100, opens May 1

- Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser, exhibition opens June 27

- Series of behind-the-scenes tours across 2020 at Blythe House, London

Staging Places Studio – the UK’s Prague Quadrennial theatre design entry

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this venue

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99