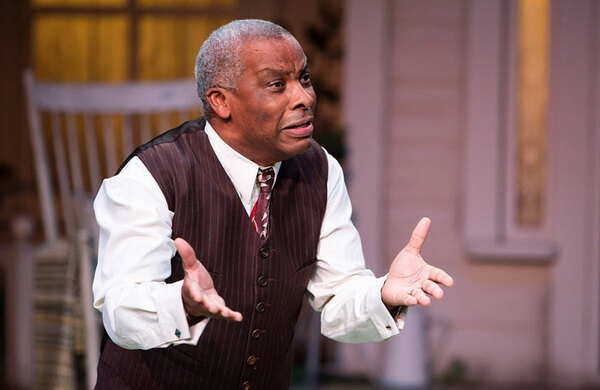

Michael Buffong: ‘Putting black actors on stage is the easy bit’

The artistic director of Talawa Theatre Company is in reflective mode: “There should be more black theatre companies. I think, in the whole country, there are three – in the whole country.” Michael Buffong sits back in his chair, absorbing his own words. “Wow,” he says incredulously. “It used to be so much more. When I was acting, there were more stories being told by more companies. We’ve gone backwards.”

I mention that, even in 2016, watching Adrian Lester take the lead role in the Kenneth Branagh-produced revival of Red Velvet, as Ira Aldridge – the real-life, black American actor who first shocked British audiences by playing Othello and then King Lear in 1860 – felt depressingly like a novelty in the West End. Buffong nods wryly. “Oh, the themes [of that play],” he says. “You just go, ‘Really, how much has changed?’ ”

Talawa is celebrating its 30th birthday this year. Founded in 1986 by Yvonne Brewster, Mona Hammond, Carmen Munroe and Inigo Espejel, it sought to create a place in British theatre for actors from minority backgrounds. Since then, the company has toured a major production annually with great success. In 1994, it staged the first black King Lear since Aldridge’s. And it is revisiting Shakespeare’s great tragedy next month, in a new production starring Don Warrington.

Three decades of existence and a return to a pivotal play in Talawa’s and British theatre’s history are good reasons for reflection. Buffong, who is directing Lear, took over as artistic director of Talawa in 2011. “When Yvonne set up the company, her thing was to get black actors playing roles they would never ordinarily get,” he says, recalling his excitement watching the company’s 1989 production of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

“I think those arguments are still happening today, absolutely,” adds Buffong, who directed Warrington in Talawa’s 2013 revival of Arthur Miller’s All My Sons. He highlights the ongoing talent drain caused by creatively frustrated black actors heading to America for its greater range of roles. But, he continues: “We now realise there’s a much bigger question at hand – who decides what’s put on stage?”

Buffong is adamant that genuine, lasting change can only come from the top down. And that means breaking open the ranks of white, middle-class men who still dominate the running and programming of British theatres.

He recognises that he’s not the first to say this. “It’s been said a hundred times. It’s about the gate-keepers and the decision-making.” He goes on: “If we have different ways of looking at the world from the top, we’ll start getting different stories,” he emphasises. And few companies have been as committed to this cause as Talawa.

To this end, Buffong’s abiding goal for the company is to maintain its “forward-looking-ness” – to build on its rich history of providing a pathway into British theatre for BAME artists at every stage of the creative process, those who can’t find an access point in the current mainstream landscape. He wants to support the decision-makers of the future.

“A lot happens through Talawa,” Buffong enthuses. “Before I became artistic director, one of my first directing jobs was [here].” He’s proud of TYPT, Talawa’s programme for emerging theatremakers – directors, producers and designers as well as actors – aged 18-25. “We’re keen on developing offstage talent,” he says. “We’re looking to bring those people in and plug them into the networks we have.”

From Lolita Chakrabarti, who wrote Red Velvet, to David Harewood, Talawa has worked with some of the most talented black theatremakers and performers in the UK. Theresa Ikoko, whose play Girls won the 2015 Alfred Fagon Award for best new play, came through Talawa Firsts – the company’s annual showcase for new writers, directors and actors.

“We’ve really invested in black British writing; we’re really pushing it,” says Buffong. “People say, ‘We don’t know how you write for theatre, we see other plays on, but how do you get there?’ ” In addition to TYPT and Talawa Firsts, three times a year the company provides a script-reading service. “New talent is being attracted to us because they see us as a place where their work can be heard, seen and produced.”

It’s not easy. “Being in this industry has more and more become something you can’t do unless you have the money or are supported,” says Buffong. So, while Talawa itself has limited finances, its role has never been more important. That word of mouth, the momentum begun by a play reading at Talawa Firsts, can travel a long way career-wise.

Continues…

Q&A: Michael Buffong

What was your first non-theatre job? Working in the Valuation Office.

What was your first professional theatre job? Assistant stage manager at Soapbox Children’s Theatre.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out? Save 10% of your income for yourself.

Who or what was your biggest influence? Seeing a youth theatre show at Theatre Royal Stratford East aged 17. On stage were young people who looked and sounded like me. Other influences have been reading The Amen Corner by James Baldwin and Malcolm X’s autobiography.

What is your most important piece of advice for anyone contemplating a career in theatre? Be passionate, and learn your craft.

If you hadn’t been a director, what would you have been? Possibly a writer.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions? I never go backstage after the half.

Diversifying the management of theatres with people from different backgrounds is key to giving emerging writers a voice. It’s about tuning into a richer, more socially representative variety of work. “It’s not hard to put faces on stage,” says Buffong. “That’s the easy bit.” The real challenge, he believes, is to get people to think differently, including about their choices when it comes to staging all-black productions.

“Are you setting Shakespeare in an African country because, somehow, it’s how you understand black actors doing Shakespeare?” Buffong asks. That’s why it’s significant that Talawa’s new version of King Lear is set in eighth-century Britain. “Because there was a black presence then,” he continues. “And this production says, ‘Actually, we’re here, and we always have been.’ ”

If black, Asian and minority ethnic-focused work in the 1980s often dealt with origins, Buffong reflects that, 30 years later, it’s now about the actual fabric of everyday British life. That’s why he views touring Talawa’s shows – tough though it is in the current climate – as so important. “There’s an appetite for good theatre,” he says. “And it’s good for places that haven’t seen this kind of work to view it and go, ‘Oh, my goodness, it’s okay, it’s fine.’ ”

While on tour, Talawa undertakes outreach work. “We go into communities, make connections and offer workshops,” says Buffong. “That’s part of our remit, what we do as standard with our productions.” But getting some venues to programme the company in the first place can be tough. “It’s that old-fashioned thing: black equals ‘risky’,” Buffong says, frustrated. “I thought theatre was about risks?”

How does Buffong stay optimistic in the face of such knee-jerk thinking, or when something like the casting of Noma Dumezweni as Hermione in the upcoming Harry Potter play causes uproar? “Sometimes it’s hard,” he reflects. “But just to do the work is fantastic. And when you’re surrounded by talented people doing things that will make a change to somebody, it’s powerful.”

From the top down, there is much to be done to make British theatre a better reflection of both artists and audiences. Tokenism is still common and the occasional all-black casting is not a solution to a systemic issue that stretches into every department of a production. In this landscape, Talawa exists importantly – as Buffong says – as “a beacon, somewhere you can go to express yourself”.

At Talawa, he says: “We decide how we’re portrayed, rather than someone else saying: ‘I’ve decided to do an all-black cast set in this specific place where I understand black culture.’ ” There are many stories to be told. “Where I’m sitting [black culture] is everywhere,” says Buffong. It doesn’t always have to be found abroad or on a council estate.

Underscoring his point, Buffong gestures outside Talawa’s London offices. “That’s the world and the society I actually live in,” he says. The wryness doesn’t hide his seriousness.

CV: Michael Buffong

Born: 1964, London

Training: Theatre Royal Stratford East’s directors’ course; assistant director at TRSE and Talawa Theatre

Landmark productions: Six Degrees of Separation, Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, 2004; A Raisin in the Sun, Royal Exchange, 2010; Moon on a Rainbow Shawl, National Theatre, 2012; All My Sons, Royal Exchange, 2013; Private Lives, Royal Exchange, 2011

Awards: Four Manchester Evening News theatre awards for A Raisin in the Sun (2010)

Agent: Independent Talent

King Lear is a co-production between Talawa Theatre Company and Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, in association with Birmingham Repertory Theatre. It runs at Royal Exchange Theatre from April 1-May 6, before touring venues around the UK

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this person

More about this venue

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99