Director Alice Hamilton: ‘As a director I believe my job is to serve the writer. Maybe that means I’m consigning myself to a slow-burning career’

Currently taking charge of two productions simultaneously, In Lipstick at the Pleasance and Dusty Hughes’ Paradise at the Hampstead Theatre Downstairs, director Alice Hamilton tells Fergus Morgan about her partnership with writer Barney Norris, working as a woman post-MeToo and what she calls her ‘slow burning’ career

If Alice Hamilton wore a Fitbit, it would be clocking up some serious mileage at the moment. The director has two shows opening simultaneously – Annie Jenkins’ In Lipstick at the Pleasance, and Dusty Hughes’ Paradise at the Hampstead Theatre Downstairs – and she is rushing between both.

“This week I’ve had to leave my assistant doing a line run for In Lipstick, whizz over to Hampstead for an hour of notes with the cast of Paradise, then whizz back again for a run through at the Pleasance,” she says. “It’s been tough, but that’s the thing with this industry. Work comes in waves. Sometimes you do nothing, sometimes you’re far too busy.”

Managing the workload, Hamilton says, is her biggest challenge as a director right now – scheduling her year, deciding whether to take a project on and making sure she stays enthusiastic, whatever she’s doing.

“Sometimes you take work to pay the bills that you might not feel passionate about,” she says. “But with every project you go into, you owe it to the people you’re working with to find that passion. It’s just about whether it comes naturally, or you have to generate it yourself in the circumstances.”

Q&A Alice Hamilton

What was your first job in theatre?

At First Sight, Up in Arms’ first production.

What was your first non-theatrical job?

I was a barista at Costa.

What is your next job?

A collaboration between Nuffield Theatres and Up in Arms on a verbatim audio play.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Go and meet Brian Friel before he dies because there might literally not be another writer that good in your lifetime.

Who or what is your biggest influence?

Probably my friend and long-term collaborator, Barney, without whom I’d have given up and done a law conversion long ago.

If you hadn’t been a writer, what would you have done?

When I was younger I had aspirations of owning a sweet shop.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

No, I don’t think so.

Hamilton has just turned 30 and the bulk of her theatrical career to date has been defined by a creative relationship with the writer Barney Norris. The work they’ve produced together as Up in Arms Theatre has been critically successful, and she’s definitely passionate about it.

The pair met as teenagers in Salisbury, when they were both in Stage65, Salisbury Playhouse’s Youth Theatre programme. Both went on to study at Oxford University, producing scores of student plays during their time there, often, Hamilton says, at the expense of her social life.

They had some small success while still studying – they took Norris’ first work, At First Sight, to Camden’s Etcetera Theatre and to Latitude in 2011 – but their first major hit came with Visitors, Norris’ first full-length stage play, in 2014.

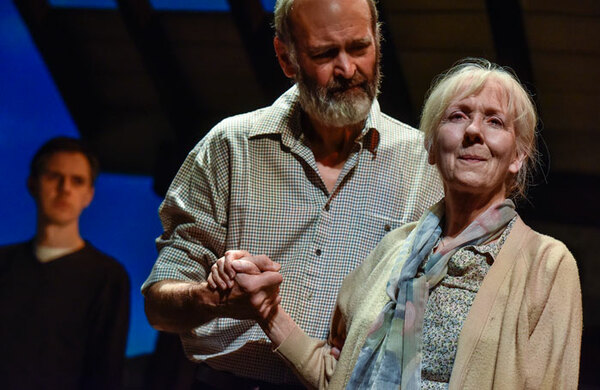

After an initial run at the Arcola Theatre and on tour, it transferred to the Bush Theatre, and received rave reviews, thanks in part to a sterling central performance from Linda Bassett.

“Visitors was huge,” says Hamilton. “We were very much scraping around before that. I was doing front of house at the National Theatre, and a lot of scratch nights and short plays, earning nothing and spending lots of money. It was quite a shock to the system to suddenly be working with such experienced people, and to be expected to be wise and articulate every day.”

With a certified success behind them, Norris and Hamilton suddenly found things easier. They produced a follow-up in 2015 with Eventide, then branched into reviving other writers’ work, staging Robert Holman’s German Skerries and David Storey’s The March on Russia at Richmond’s Orange Tree Theatre.

They revisited the Bush in 2017 with While We’re Here, and returned to their teenage alma mater, Salisbury Playhouse, with Echo’s End the same year.

Their work together focuses on small stories, often historical and often in a rural setting. Hamilton freely admits their stuff isn’t exactly “trendy”.

“Quietism,” says Hamilton. “That’s the word that’s often used about our plays. We are interested in shining a light on different communities, forgotten communities, within specific geographical contexts.”

Hamilton understands that, with this focus on understatement, she might not be the sort of director to make a big splash with her visionary stagings.

“As primarily a new-writing director, I see my job as to serve a play, so necessarily it is the writer’s work on stage, rather than the director’s,” she says. “It’s about the play, not what I’m doing with it. But that means I am probably consigning myself to a slow burner of a career.”

Correspondingly, she’s philosophical about the fact that Norris’ most recent play, Nightfall, was staged at the Bridge Theatre last year but didn’t involve her at all, the first of the writer’s work not to do so.

“Careers go at different paces, and it was challenging for me because of all of those projects we built together,” she says. “But people running big buildings are legitimately wary about trusting those spaces to directors who have only worked in small spaces before. I would like to have been involved in that conversation, but it wasn’t to be.”

She’s confident her time on big stages will come, though. “I feel very fortunate to be making a career at a time when people are so conscious of the historic gender imbalance in theatre,” she says.

“Because there is such an effort to address it right now. I feel I have been actively supported to develop my career. If I were to go for a big job, I would have as good a chance of getting it as a male contemporary.”

For now, she can only focus on the job, or rather jobs, at hand. In Lipstick, she says, is “a bit outside my comfort zone”, she says. “It’s a darkly comic, topsy-turvy fairytale for the modern day. And it’s an absolute stage management nightmare. We have 10 Shirley Bassey songs, fighting, dancing, sex, 31 chicken McNuggets meals from McDonalds, and a huge meat feast picnic.”

She adds: “Getting our heads around the emotional through-line of a story, while also finding the wit and humour of it, and then organising practical stage management – it’s been a real challenge.”

Hughes’ Paradise, meanwhile, is “very different”, she says. “It’s about people looking back on their lives, with a bit of mischievous wit thrown in,” Hamilton says. “The challenge with that isn’t: How do we cope with getting all these chicken nuggets on stage? It’s bringing to life the ramblings of these two women.”

Although Hamilton admits taking charge of two productions simultaneously has been tough, she thinks it’s also been educational. “It’s good to put yourself through something like this every now and again,” she says. “But I probably wouldn’t do it again, though.”

CV Alice Hamilton

Born: Swindon, 1988

Training: BA in classics from Magdalen College, Oxford

Landmark productions:

• Visitors, Arcola and tour (2014)

• Eventide, Arcola Theatre (2015)

• German Skerries, Orange Tree (2016)

• The March on Russia, Orange Tree (2017)

In Lipstick review at Pleasance Theatre, London – ‘sympathetic and warmly performed’