The Height of the Storm

“Disorientating and melancholic”

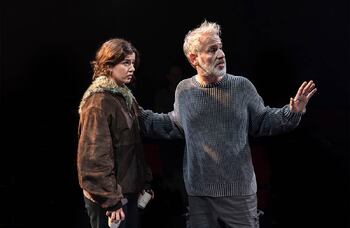

Eileen Atkins and Jonathan Pryce in The Height of the Storm at Wyndham's Theatre, London. Photo: Tristram Kenton

THIS IS NOT A PAYWALL

Serious about theatre?

Join over 100,000 theatremakers who rely on The Stage for trusted news, reviews, and insight.

🔓 Sign in below or create a free account to read 5 free articles.

Want to support independent theatre journalism? Subscribe from just £7.99 and unlock:

🗞️ Unlimited access to award-winning theatre journalism

⭐ 1000+ reviews from across the UK

📧 Breaking news and daily newsletters

💡Insight and opinion from writers including Lyn Gardner & Amanda Parker

🎟️Discounts and early access to The Stage’s events

More Reviews

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99