The Almighty Sometimes

Anna is contemplating leaving home. She craves independence. She wants to go to university. She is 18 years old and that’s what 18-year-olds do. But Anna has also been on medication since the age of 11. Seven years ago, her mother, alarmed by her young daughter’s increasingly volatile and self-destructive behaviour, sought a diagnosis for her child. Anna’s life since then has been one of pills and vigilance.

Kendall Feaver’s impressive debut play – winner of a Bruntwood judges award in 2015 – explores the ramifications of that decision for both Anna and her mother. It’s a carefully weighted piece of writing, exploring both mother and daughter’s perspectives without ever hammering home the fact that this is what it’s doing.

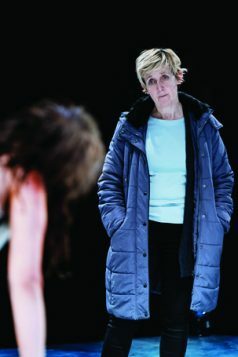

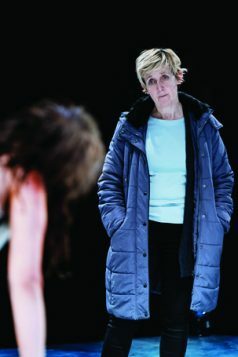

Anna’s mother Renee – played with typical dignity by Julie Hesmondhalgh – is forever wrestling with the fact that she has set her daughter down a particular path in life, that in seeking treatment for her, in trying to help her – to save her – she might have stifled her.

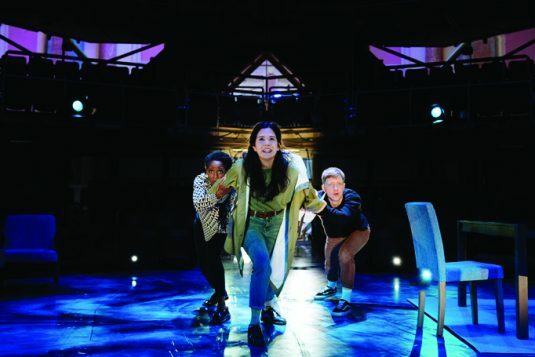

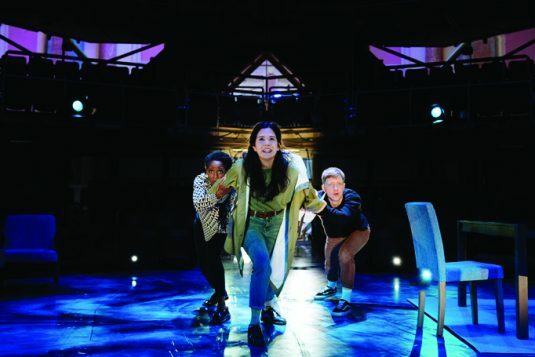

Anna is played with fight and fire by Norah Lopez Holden. She is resentful of the fact that such a huge decision about her development was made without her say-so and increasingly curious about the person she might be without the medication. She frets that she will never be able to truly express herself creatively if she remains on her meds. It’s a large, stage-dominating part, and Holden nails Anna’s mix of arrogance and vulnerability, mania and pain.

The potential intensity of the set-up is diluted by the presence of Oliver, Anna’s boyfriend. He’s a kind, generous character, played with fine comic timing by Mike Noble. There’s a suggestion that his relationship with Anna is intertwined with his own deprived upbringing. He cares because care has not been shown to him. There’s similarly strong work from Sharon Duncan Brewster as Anna’s psychiatrist, who at times seems tempted to overstep the boundaries between patient and doctor.

Feaver’s play balances humour with moments of emotional acuity – there are some haematite lines in here, dark, witty and glinting. But Katy Rudd’s production becomes less sure-footed and more cliched in the scenes when Anna’s experiment in withdrawing from her meds goes awry and she ends up hospitalised. As Anna retreats into her illness she creates a void in the play. But, even during these lulls, it never relinquishes its grip.

The action plays out on Rosanna Vize’s heptagonal stage. Lighting designer Lucy Carter has created a rig that, in the production’s most overtly theatrical – and least subtle – moment, descends from above, trapping Anna in her own mind.

While the writing speaks of research and sometimes seems over careful, it’s the nuance and complexity of the mother-daughter relationship that really stands out. Together Holden and Hesmondhalgh capture the complicated mixture of affection, tenderness, need, dependency, frustration and occasional cruelty that can exist between a parent and their child.

Wit review at the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester – ‘heart-battering’

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99