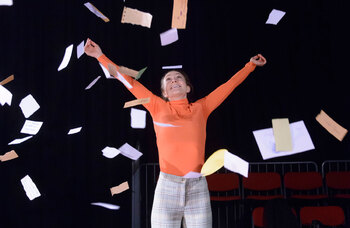

In the Weeds review

New play bathed in folklore gets bogged down in clichés

In the Weeds is a play full of folklore. Set on a Hebridean island, it dabbles its toes in the myths and legends of two cultures, Scottish and Japanese. Out of these mishmashed tales of the deep emerges an almost-love story with murderous overtones. But while the premise is as enticing as a cool dip in a still loch, the result is muddied and hard to navigate.

Written by Joseph Wilde and directed by Rebecca Atkinson-Lord for An Tobar and Mull Theatre, where Atkinson-Lord is artistic director, this is the second collaboration between the pair following Cuddles, which is currently being adapted into a film produced by Nicole Kidman’s Blossom Films. The story positions itself as an unlikely friendship-slash-romance between local girl Coblaith (Carla Langley) and incomer Kazumi (Jamie Zubairi).

Kazumi is a marine biologist who is scared of water and has found his way to the Scottish shores in search of an unknown sea creature, which may or may not be real. Instead, what he finds floating in the shallows is Cob, an ostracised islander who seems to spend all her available time avoiding being on dry land.

Langley’s Cob is full of spikey contradictions. She is as old as the hills (or the island itself) and yet simultaneously naïve. Zubairi’s Kazumi, meanwhile, is geekily unsure of himself and tightly wound.

The pair trade cultural knowledge. Cob tells Kazumi the colloquial names of flowers he can only identify using the Latin, regales him with stories of kelpies and selkies, and takes him to one of the thin places. Kazumi, in turn, introduces her to Shinto philosophies and practices, discusses the souls of mussels and brandishes his dad’s sashimi knife like an ancient relic.

Sometimes, this works nicely, but at other times it veers dangerously close to indulging in cultural stereotypes and predictable reference points. Neither culture comes off particularly well, both feel – at various points – either reductively or romantically portrayed. Cob’s allusions to the history of the island and the former incomers who have seized and named it is more interesting, but underdeveloped.

The show comes undone when we get to another version of an age-old story: violence between men and women. It feels like Wilde doesn’t quite know how to navigate the territory he wanders into here. It’s not glorified, but it’s also unnuanced, with the feel of lo-fi horror.

It’s a shame because the starting idea – and the eerie sunken set by Kenneth MacLeod – are attractive and promising. Perhaps it needs to be less concerned with the mythological and more with what genuinely feels ‘real’.

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99