Hamlet review

Shakespeare gets lost at sea in Rupert Goold’s Hamlet, starring Luke Thallon

There is a lot to distract you from the Shakespeare in Rupert Goold’s Hamlet at sea for the Royal Shakespeare Company – not least the fact that the production is seemingly set on the Titanic. Or at least, a boat that, like the Titanic, starts to go down in the middle of the night on April 14, 1912. Denmark is a sinking ship under its new leadership – and aboard this vessel are Luke Thallon as a psychologically tormented Hamlet, Elliot Levey as a jobsworth Polonius offering light relief, and Nancy Carroll as a waspish Gertrude. Shakespeare’s text, meanwhile, gets drowned out in the highly stylised production, in which the verse is tinkered with to such an extent that it loses its flow, and characters often struggle to be heard above the din of the busy ship.

The wordless shouts and twitching body of Thallon’s Hamlet hint at Tourette syndrome, while his outburst at Nia Towle’s Ophelia, followed by his later joviality, seems to suggest that he may have bipolar disorder. But Thallon is let down by an interpretation that requires him to deliver lines as if he’s struggling to remember them, with long pauses and mono-tonal outpourings that forgo all sense of rhythm. He’s also more clownish than brooding, throwing frequent exaggerated grimaces to the audience.

Continues...

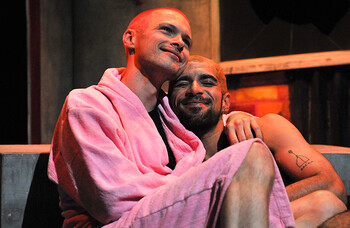

These mannerisms become muted in the second half, which lends the production an inconsistent feel. But fortunately, it otherwise stabilises here, as Carroll’s Gertrude and Jared Harris’ Claudius – whose loyalty to the meter seems almost to belong in a different staging – become stronger presences.

Es Devlin’s set is a mist-shrouded deck – enlivened by Adam Cork’s rumbling, creaking, dripping soundscape – that tilts on an axis and overlooks an increasingly choppy sea. Crew members toil with ropes, while a digital backdrop of rolling waves from video designer Akhila Krishnan creates the nausea-inducing sensation that this vessel is always in motion. If it brings motion sickness right into the auditorium, it’s still a visual and technological feast – the lifelike rippling waters could almost be a precursor for the RSC’s upcoming venture into video games.

There’s an unnerving darkness to this production, which imagines the entire story playing out over the course of one claustrophobic night. The stage is flanked by a pair of glaring red digital clocks, counting down the hours to disaster. When it strikes, and bodies start sliding off the upturned deck, Thallon appears to defy gravity, rising from the arms of Kel Matsena’s Horatio to deliver his closing speech standing, arms spread wide. Like much else here, it’s a spectacle that needs to be seen to be believed, in a production that too often feels overwhelmed by visuals and concept.

More Reviews

More Reviews

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99