Death of England: Closing Time review

Concluding part of the state-of-the-nation trilogy is vivid, intense and thrillingly performed by Erin Doherty and Sharon Duncan-Brewster

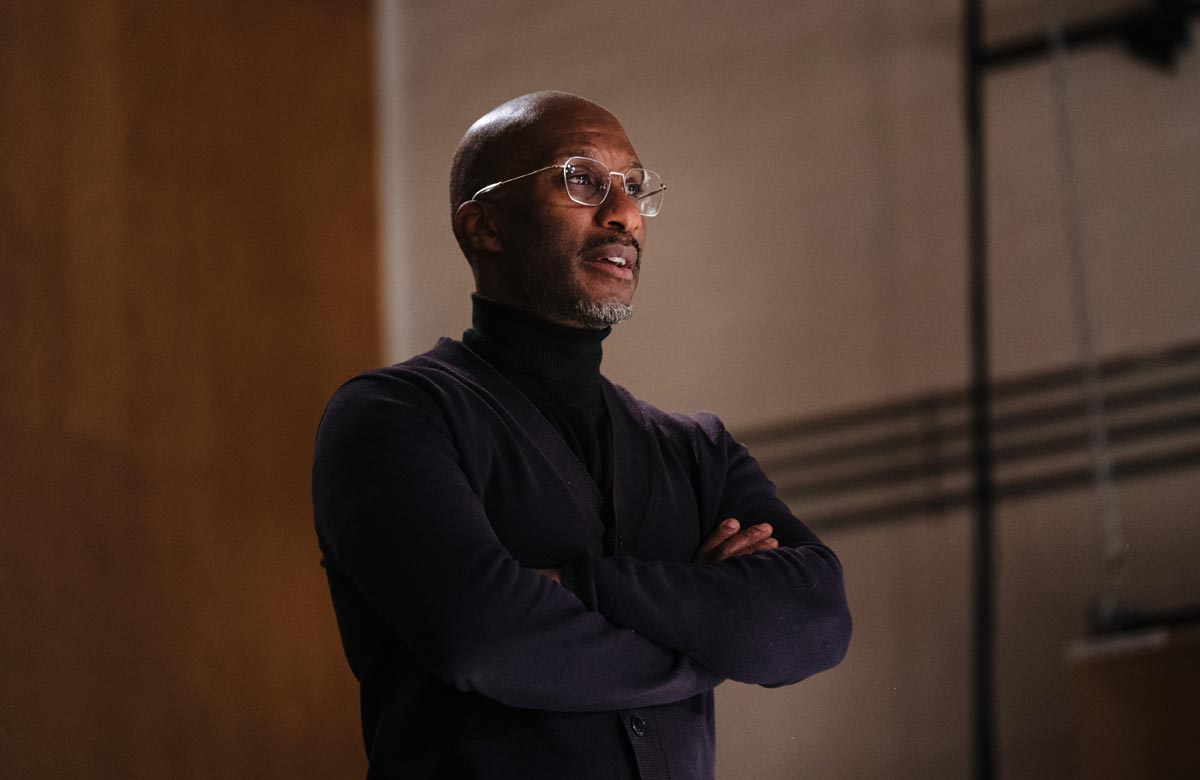

And so Clint Dyer and Roy Williams’ intimate-yet-epic state-of-the-nation trilogy reaches its end, with this two-woman face-off in which a war of words is waged, and an uneasy peace brokered, over issues of race, class, family, love and betrayal. Like the two preceding plays presented, in Dyer’s productions, in this West End season, this one is at times over-deliberate and unsubtle in its drawing of direct connecting lines between the personal and the political. But, where the other pieces are monologues, this is instead a kind of hybrid that switches between fervid, direct-address confessionals and confrontational dialogue. Such is the scorching talent of Sharon Duncan-Brewster and Erin Doherty that the solo set pieces are riveting – but the writing reaches its most potent intensity when they interact. The acting is flawless; the motor of Dyer’s staging, it purrs, snarls, revs and roars, powering even the less fluent passages of the text into overdrive.

We previously met Michael, son of a racist, white flower-stall owner, struggling to come to terms with his father’s death and legacy; then Delroy, his best friend since schooldays, who is Black. Now we find Carly (Doherty), sister to Michael and girlfriend to Delroy, and Denise (Duncan-Brewster), Delroy’s mum, in the process of closing down their joint business: a florist adjoining a Caribbean takeaway. Covid is partly responsible for the venture’s failure; but there’s also been a shocking incident that has destroyed their reputation and ruptured their close relationship. Is Carly more her father’s daughter than she cares to admit? Can understanding be reached, and love survive, when hurt is so profound?

Continues...

Doherty’s Carly, radiating sex and swagger, brilliantly combines the tough and tender, as well as morphing miraculously into her blustering dad and a teenage memory of her brother at his most gawky and gormless. Duncan-Brewster, meanwhile, is a volcano of grief, pain and fury, elegantly smouldering between red-hot, lava-spitting eruptions. They sling words back and forth at each other, and at us, weighing up the damage that might be done or the points scored and proven, rolling the choicest lines around their mouths with casual relish. The dramatic texture is vivid as well as combative, and often richest in its smaller details. Carly recalls her father stroking her face with “rough sausage fingers”; Denise describes the sweaty, heart-flipping horror of staring at her phone as the online evidence of Carly’s awful treachery goes viral. The piece is strong on the blood sport and mob mentality of social media, faceless commenters queuing up to castigate and punish moral transgressors. And in a flashback scene in which the family gathers to watch Charles’ coronation on telly, there’s a delicious takedown of the archaic, pantomime privilege of the Royal family; Carly and Delroy’s baby daughter is named Meghan, a mischievous touch.

But this is above all a play about England itself, which has even been updated to include mention of the recent riots; a portrait of a country of push and pull, angry, confused and afraid, but where there is also striving for connection and hope for greater harmony. Line by line it may not always fully convince; yet as a whole, the trilogy feels like work of genuine historical significance. And it could hardly be more thrillingly performed.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99