Death of a Salesman

The power of Arthur Miller’s 1949 Pulitzer-winning play is the way in which it operates on so many different levels. It’s simultaneously a commentary on capitalism and the American dream, an evocative memory play, and a poignant portrait of one man falling apart.

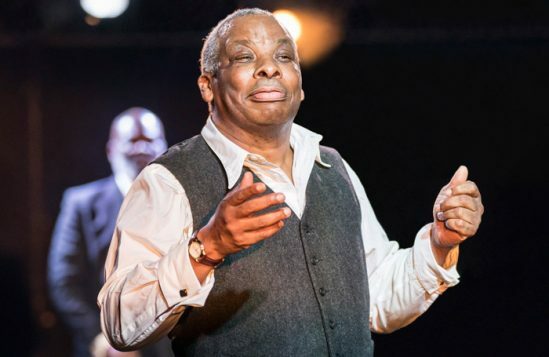

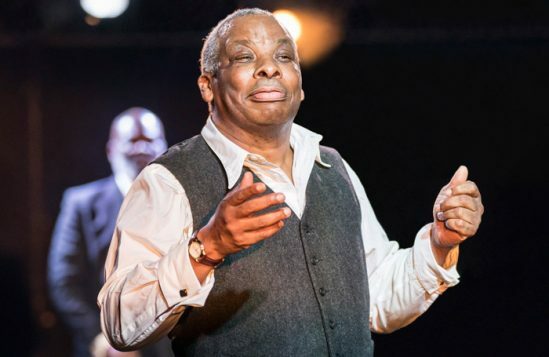

The character of Willy Loman is a mountain of a role and Don Warrington, returning to the Royal Exchange after a triumphant King Lear, hurls himself into the part.

At the age of 63, career salesman Loman has been reduced to working off commission and driving miles for little reward. Warrington conveys Loman’s pride, and his deep desire to be liked and known everywhere he goes, but it’s all a lie – he’s barely clinging on. Faced with obsolescence, he retreats into his past – and into his head.

Warrington is physically imposing as Loman. He has the slick demeanour of a salesman down to a tee, but he can also be petulant and child-like, blowing hot and cold, his gestures sad and small.

Sarah Frankcom’s intelligent in-the-round staging draws out the fact that Miller’s play is one of circles, in which memory, dreams and dashed hopes are intermixed. Leslie Travers’ poetic set consists of a large copper-coloured disk that resembles an eye. Above this hangs a canopy of greenery, while a simple kitchen table represents the Loman home, the mortgage payments on which are nearing completion. The design, with its slightly fantastical forest-like quality, heightens the sense of this being a dream play, one in which internal and external worlds are blurred.

The supporting characters sit around the edges when not on stage, watching Willy, haunting him. The most notable ghost is Willy’s brother Ben, played by the sonorous Trevor A Toussaint. Ben went to Africa and made his fortune young, and the shadow of his success still looms over his brother, even after death.

Maureen Beattie’s fiercely protective Linda Loman makes a real impact during the sometimes slow-moving first half. Though her life has been far from easy, she can’t contain her anger with her sons when she feels they do not appreciate their father as they should. The production tightens its grip in the second half as the tensions between Willy and Ashley Zhangazha (another Royal Exchange returnee) and Buom Tihngang, as sons Biff and Happy, intensify. However, some of the big emotional moments feel muted.

Frankcom’s production is detailed and cerebral. It makes the play feel contemporary in its depiction of fragility and of men buckling under societal pressure to provide, while waking up to the fact that the world is changing too fast for them to keep up with. The casting also provides a new lens through which to view the play, as an exploration of race and social mobility in America.

Despite some wavering accents and an occasional lack of clarity in the shifts between past and present, the performances are compelling and Frankcom’s production, though more intellectually than emotionally engaging, makes for a layered and fascinating reframing of a classic.

Don Warrington: ‘If I were starting out today, I’d certainly go to America’

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99