Anniversary staging of George Orwell’s classic is visually striking, but emotionally unengaging

When George Orwell his seminal novel, 1984, he envisaged a dystopian world where human emotion and nuance were all but eradicated in favour of the formulaic and controlled. This new stage adaptation, directed by Lindsay Posner and adapted by Ryan Craig to coincide with the book’s 75th anniversary, succeeds in creating the stilted, emotionless world of Big Brother – but not necessarily for the right reasons.

Mark Quartley’s Winston Smith is a repressed, nervous worker who first catches the Party’s attention for using one too many “old-fashioned” adjectives in his Newspeak rewritings of articles. Despite his unprepossessing attitude, he becomes romantically involved with Eleanor Wyld’s Julia, who has the air of someone who loves to chat to strangers on trains while sitting in the quiet coach.

Their love affair, conducted in woodland glades and a so-called safe house, happens at breakneck speed, although there appears to be little true chemistry between the pair. The architect of their downfall, O’Brien, is played by Keith Allen, who avoids being totally menacing and instead channels a sadistic schoolteacher. more pathetic than terrifying. But perhaps that is the point: the small-scale fascist who loves to use their limited amount of power is, in a sense, just as scary as the crazed political party leader.

Continues...

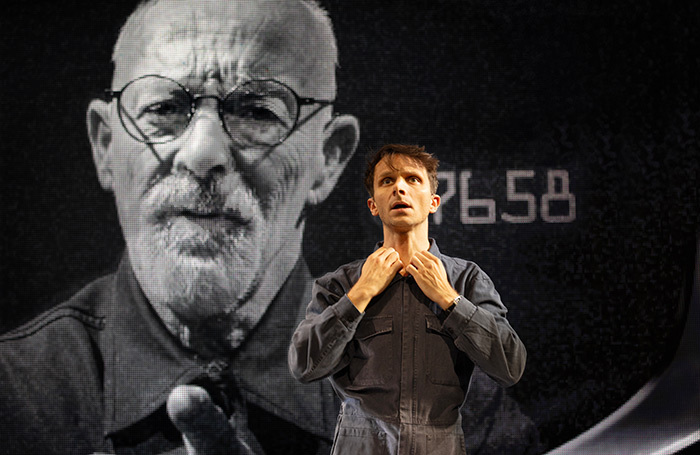

The production’s main strength Justin Nardella’s, set, costume and video design. Pre-recorded footage features an additional nine cast members, and there’s a sincerely beautiful moment where an image of a young girl is projected on to a translucent screen as Winston’s dream/nightmare floats surreally around his supine body. The infamous Big Brother screen is here rendered as a cross between a giant lidded eye and a retro television screen.

Integrating so much video is an interesting choice that both adds to and detracts from the overall effect. At its best, it brings a slick, exciting aspect to the show. At other times, it overbalances and draws the spotlight away from what the actors are actually doing on stage.

Maybe that’s deliberate – to demonstrate what happens when people are overpowered by screens – but Posner’s production saps the human element from Orwell’s story. It’s hard to invest fully in scenes of torture or a tale of childhood woe when emotion is only conveyed by flat voices and highly stylised gestures. The text references timeless poetry, epic art and freedom of thought. But here, everything seems static and lacking in true feeling.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99