The changing face of criticism and artistic directorships

The changing role of criticism in the internet age is being much discussed, not least in this column. And two events this week – one in Canada, one here in the UK – will discuss it live in person.

On Saturday, the UK’s Critics’ Circle are, as I pointed out yesterday, holding an event at the Victoria and Albert Museum entitled ‘The Art of Criticism’. At the free public event, representatives of all five sections of the circle – theatre, film, music, art and dance – will be on hand to discuss the past, present and future of what we do.

But before that the Canadian Journalism Foundation will on Thursday offer a more provocatively titled session, ‘The Walking Dead: Do Traditional Art Critics Have a Future?’ in Toronto. The panel includes Robert Cushman, one-time theatre critic of The Observer in the UK who now writes for Canada’s National Post, and Ben Brantley of the New York Times.

In an interview with the Toronto Star, Brantley has already set out his stall on some of the issues confronting reviewing today, or what passes for it. In the New York system, where critics are invited to critics’ previews a few days ahead of the opening, then file a review that is published on the day after the opening (but usually online the night of the opening), he has the luxury of time and says:

I like a bit of time to digest. I don’t think you should go with your very first instinct. There should be a chance to process what you’ve seen.

Of course, “overnight critics” in London – those who rush to file their reviews within an hour or so of curtain down – don’t have that luxury. But the new wave of bloggers and tweeters don’t necessarily even wait that long.

As the Toronto Star’s Richard Ouzounian remarks to Brantley, “Some of them go to the first preview and post their ‘reviews’ at intermission.” And as Brantley sagely replies,

I frankly don’t understand them. I don’t think theatre is sports. You don’t say who won or who crossed the finish line first. There’s a lot of noise out there but it hasn’t really changed how I do my job.

Nor does Brantley tweet:

I don’t want to have to express my opinion in 140 characters. That’s like writing haiku. You need a certain amount of legroom to review a play properly.

And reviewing properly means, too, having editors to monitor what he writes, whereas online reviewers are mostly ‘self-policing’ (and self-editing). As Brantley notes in response to this,

Ideally there should be accountability, but the internet is still frontier land. In the years to come we’ll see whether it gets better or worse. I think it’s open to discussion. It all depends on what function you want critics to fill.

Variety isn’t the spice of life

Continuing the theme of the changing face of criticism, you sense that some outlets are just about giving up the fight. Last week I noted how Variety, the once pre-eminent US trade paper, had failed to re-review the Broadway opening of Matilda, reprinting its review of the Stratford-upon-Avon opening over two years previously instead.

And now it has done it again, for Sunday’s opening of the Broadway transfer of Alan Cumming’s one-man Macbeth, first produced by the National Theatre of Scotland last June, when Variety’s Mark Fisher reviewed it at the Tramway in Glasgow. Variety has now reprinted that review, too, instead of re-reviewing it on Broadway; at least, unlike Matilda, the cast hasn’t changed, but the production surely has, not least from being put in front of a different audience (which of course it gets every night) but also the time it has taken to get to Broadway.

Variety, however, appends this note to its republication:

The following is Mark Fisher’s original review (June 18, 2012) of the show’s initial staging as part of the Edinburgh Intl. Festival last year, prior to a Lincoln Center Festival stint later that summer. Credits have been updated to reflect changes for the Broadway version.

But not, evidently, noting that the initial staging was not part of the Edinburgh International Festival at all, which a trade paper might be expected to know takes place in August, not June.

Handing over to the writers and reconfiguring the toilets

Artistic directors have to make sometimes bold, sometimes mundane choices; and the two extremes were well illustrated last week.

On the one hand, last Friday morning we had Vicky Featherstone’s announcement of her inaugural summer season at the helm of the Royal Court, in which she has handed the keys to the writers that are its backbone to programme a dazzling-sounding six week festival of new writing, from a repertory play season in the main house to readings by playwrights themselves of their own plays in various locations around the building.

This “summer fling”, as she endearingly dubbed it, will also include the return of the Theatre Local scheme initiated by Dominic Cooke, with runs of two productions – one new, one imported – at the Rose Lipman Building in Haggerston, N1 and the London Welsh Centre respectively. The new show is the sort of acclaimed American new writing that the Royal Court might have been expected to house at its home theatre – the UK premiere of Annie Baker’s New York hit Circle Mirror Transformation – especially with its stellar cast led by Imelda Staunton and Toby Jones. The import is from Featherstone’s former home National Theatre of Scotland, with its Edinburgh fringe hit The Strange Undoing of Prudencia Hart.

On the other hand, Josie Rourke – whose own new production of Conor McPherson’s The Weir opens at the Donmar Warehouse on Thursday – told The Observer last Sunday about her future plans for the Donmar once the building comes under its own ownership in 2016.

It sounds shallow, but I’m completely obsessed with making sure that it has a great bar and a lot more loos, and I want to take this opportunity to apologise to the public for the loos at the Donmar. In fact, maybe I should get rid of all the bars and install 87 loos instead.

But it’s precisely the sort of thinking that’s required when running a building, and not something that every artistic director wants to think about. As Rourke also points out, when talking about the absence of female artistic directors more generally,

Well, there are directors who don’t want to do the bit of the job that involves fundraising, HR, management, programming, budgets, reporting to boards, reporting to the Arts Council and talking to journalists about the cultural landscape. They’re very clear about that, and I think that’s OK. There isn’t a requirement to do it.

Opinion

More about this person

Advice

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

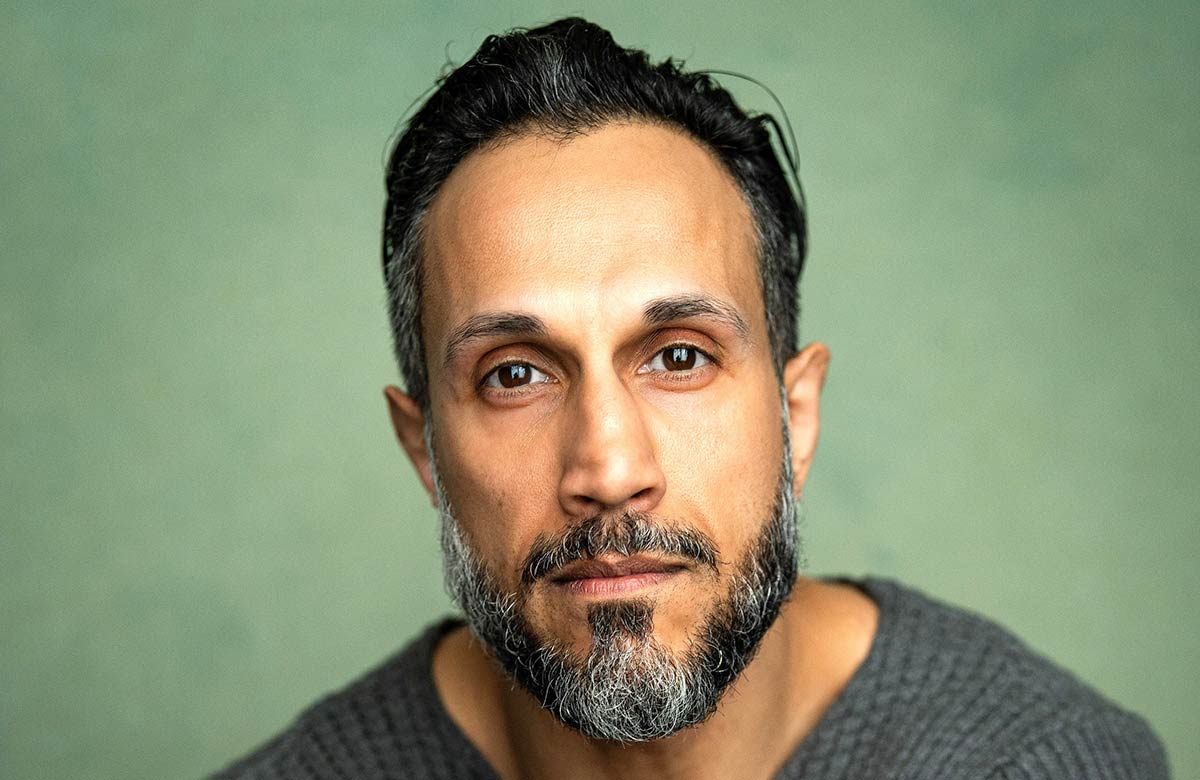

Mark Shenton

Mark Shenton