David Benedict: Les Mis is not the only classic show to beat the vicissitudes of time

Regrets, as Frank Sinatra was given to singing, I’ve had a few, but then again is missing the musical Time among them? For those too young or too busy to attend one of the 777 performances at the Dominion Theatre that started in April 1986, this was the musical extravaganza in which Earth was put on trial before the High Court of the Universe. But thanks to the valiant efforts of spiritual rock star Cliff Richard (I’m not making this up) our planet was saved courtesy of the universe’s Ultimate Word of Truth, aka a hologram of Laurence Olivier. (Yes, you read that correctly.)

So I never saw it, and have no regrets. What I seriously do regret missing, at the same address, was Bernadette, the only West End musical about a French woman who had visions of the Virgin Mary ever to have been part-funded by coffee mornings with the show’s writers in Shrewsbury. Roasted (pardon the pun) by the critics, it lasted three weeks.

What I also regret is not having been at the closing on Saturday night of Les Misérables, not least because of the champagne-soaked atmosphere and the rapturously received curtain speech by the Jean Valjean of Dean Chisnall which, happily, has been posted on

The show itself is far from ending. A glossily cast staged concert version opens next door at the Gielgud Theatre next month before the touring version reopens at the renamed Sondheim Theatre at the end of the year.

And Les Misérables is not the only legendary piece of theatre writing that has beaten the vicissitudes of time. News arrived this week that An Inspector Calls is returning for another UK tour.

David Benedict: It’s not just shows, theatres thrive on imaginative reworkings too

It’s the umpteenth return for the awards magnet that is Stephen Daldry’s inspired, expressionist rethink of JB Priestley’s gripping thriller about social responsibility. It boasts a wildly imaginative set by Ian MacNeil lit with consummate flair by Rick Fisher, the triumvirate who pulled off a similar trick creating the British musical theatre triumph that was Billy Elliot.

Contrary to most people’s memories, An Inspector Calls began not at the National but as a one-off production at York Theatre Royal in 1989. Daldry and his team then reworked their vision of it for his 1992 National Theatre debut, and the production has been seen as strikingly appropriate to our time pretty much ever since, with at least seven national tours (and international ones) plus around eight years’ worth of runs at the Aldwych, the Garrick, the Playhouse, the Novello and Wyndham’s theatres. (Has any other production played as many West End houses?)

Side note: Want a long West End run without singing? Produce a thriller – the success of An Inspector Calls is rivalled by little other than 30 years of the spine-tingling The Woman in Black (reader, I screamed) and 65 years of The Mousetrap (reader, I didn’t).

On the other hand, time can do strange things to drama. In his recent rave review of the Almeida’s production of Thomas Vinterberg and Tobias Lindholm’s 2012 film The Hunt, Tim Bano pertinently raises a question over the timing of presenting a drama about believing/not believing alleged victims of abuse, a matter that feels very different in 2019. For Tim, the production more than proves the worth of its timing. I have more misgivings about it, though none of them are about Rupert Goold’s riveting production that harnesses acting, design and lighting teams working – magnetically – as one.

At the opposite end of the equation, the business of timing similarly haunts Europe, Michael Longhurst’s eagerly awaited Donmar directorial debut. Although tonally poles apart from his recent Amadeus and Caroline, Or Change, Longhurst again proves his ability to marry design elements to writing in a way that utterly invigorates and ignites text.

At its 1994 premiere, David Grieg’s Europe felt like a play about what was happening ‘there’. Set at a railway station in the autumn of a small, decaying, unnamed provincial border town, it charts the feelings of townsfolk faced with refugees. A quarter of a century later, his astonishingly prescient play not only feels as if it is about ‘here’, it also seems as if it were written yesterday.

Time has underlined Greig’s presentation of society’s increasingly vicious lack of understanding. It comes laced with welcome flashes of hope and humour, often thanks to the superb Ron Cook (has he ever been less than terrific?), but the misplaced blame and mounting intolerance coursing through the play makes it feel like an urgent frontline report from the Brexit of the scarily close future.

Read David Benedict’s columns every Wednesday at thestage.co.uk/author/david-benedict

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

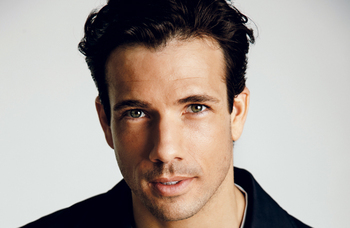

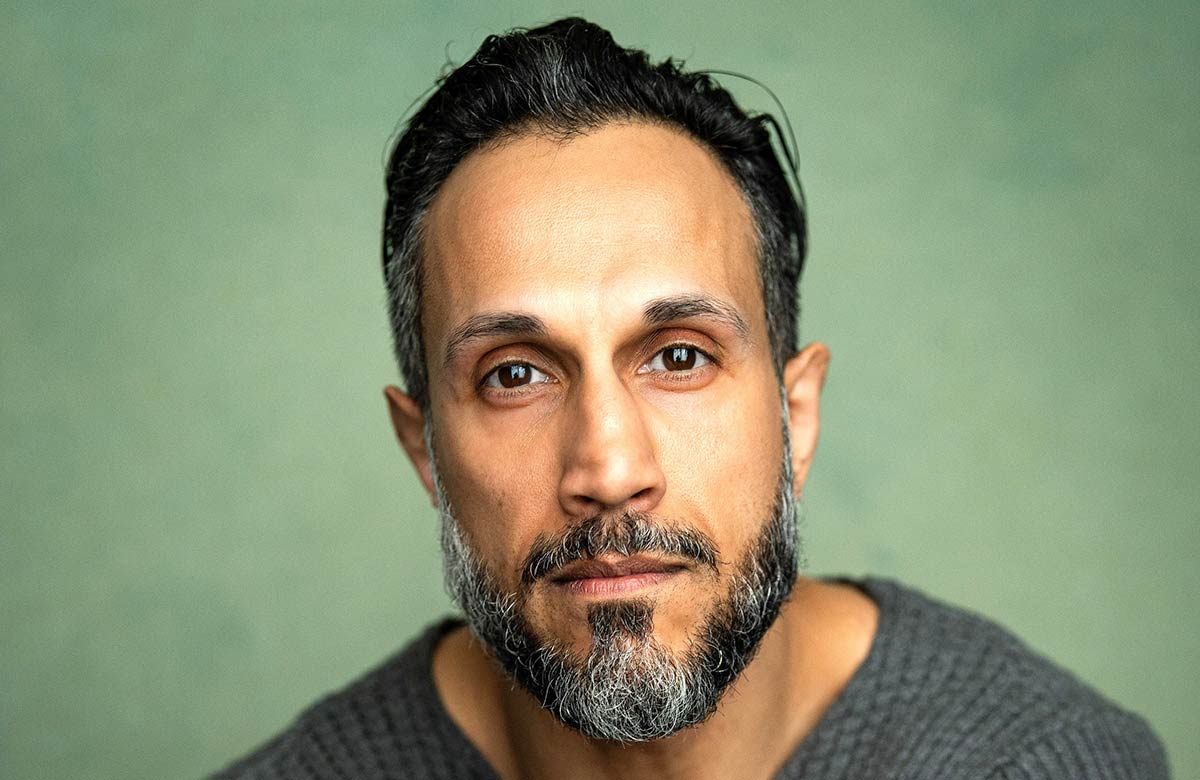

David Benedict

David Benedict