Ivan Kyncl: Looking through the lens of a theatre photography pioneer

A new exhibition at the V&A documents the work of the acclaimed photographer. Nick Smurthwaite finds out how a chance meeting with Harold Pinter and a friendship with RSC’s Terry Hands changed the face of UK theatre photography

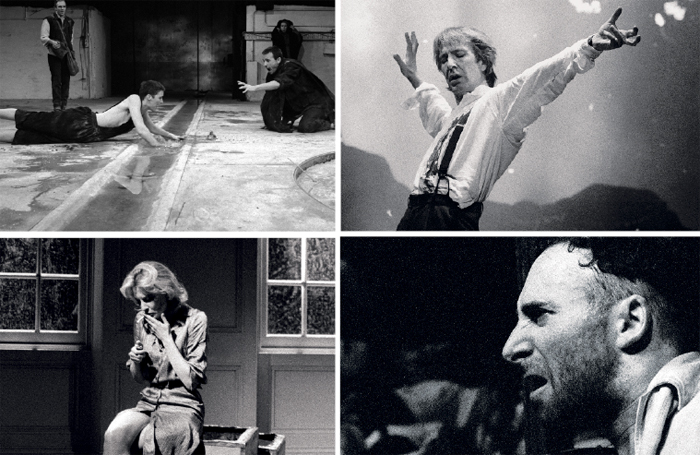

Former photojournalist and political refugee Ivan Kyncl is credited with transforming the face of theatre photography in the UK. Last year, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum bought his collection of more than 1 million images, which it describes as “one of the richest chronicles of the British stage in the late 20th century” and has put a selection of the best on display.

Having been virtually hounded out of his home country of Czechoslovakia because of his active opposition to the oppressive communist regime, Kyncl fled to London in 1980, a stateless refugee.

Kyncl not only documented the persecution of Czech dissidents by the secret police, but managed to smuggle his pictures out of the country, so that they could be published by the European media.

Granted asylum by the British government – the Czech authorities had by this time revoked his citizenship – Kyncl arrived in London speaking no English and with only his camera as a means of making a living. But by the mid-1980s he had established himself as a sought-after production photographer of exceptional talent and originality.

A chance meeting with Harold Pinter led to Kyncl being commissioned to take some publicity pictures for the 1984 production of his play, One for the Road, at London’s Lyric Hammersmith. Kyncl’s pictures were used to illustrate the published play text, and Pinter invited him back to do the production photography on his next show, Other Places, in the West End.

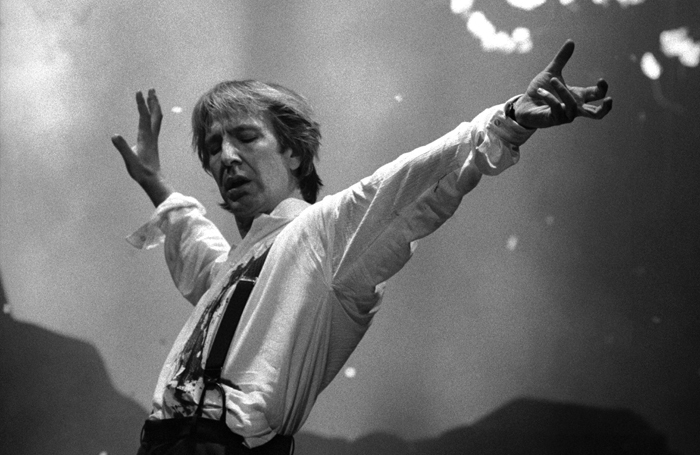

Seeking further theatre work, Kyncl approached the Royal Shakespeare Company – then run by Terry Hands – who takes up the story: “When I saw his pictures, I asked Ivan to photograph the Peter Barnes play Red Noses. The results were as wild and anarchic as the play itself. Looking back, Ivan’s photographic record of the play makes whole scenes look better than they actually were.”

Hands and Kyncl became close friends, and the latter went on to become the RSC’s house photographer, covering some 50 shows in Stratford and London, as well as working for the Almeida, Royal Court and National Theatre in the capital.

In Hands’ estimation, Kyncl was “the Henri Cartier-Bresson of theatre photographers. He was an artist with the ability to catch in a millisecond the essence of a scene or performance, and sometimes the image of an entire play in a single shot.”

The actor Antony Sher jokingly nicknamed him “Ivan the Terrible” because “his passion for work went way beyond the call of duty”. While photographing a preview of the play Primo, based on Primo Levi’s Auschwitz memoir, at the National in 2004, Sher recalls Kyncl “skulking around the side of the Cottesloe, hoping for one more shot, one more chance, and now and then darting in to grab it.”

Despite his persistence and perfectionism, actors were happy to tolerate his presence. “Actors grew to love him,” says Hands. “He would get on stage with the actors, but somehow he became invisible.”

Producer Caro Newling, who worked with Kyncl at the RSC and the Donmar Warehouse, recalls this balletic balancing act at photo calls: “He would work perilously close to the actors, shadowing and absorbing their performances with a sixth sense. He almost became part of the production. He shimmered with energy, focus and empathy. It was this that gave him unique licence to integrate creatively to this degree.”

Newling continues: “At the end of a shoot he would be utterly spent and yet, within hours, came the phone call from his Battersea studio – ‘Ready’. Then he would unfurl copious film stock that captured the very essence of what had happened earlier.”

Award-winning designer Vicki Mortimer recalls “the dynamism and lyricism” of his photography. She says: “What was very appealing to me as a designer was that Ivan didn’t just take pictures of actors – there were no static headshots. He always managed to find the essence of a show. He seemed to have an intuitive understanding of what the aim of a show was. What he did was a radical departure from the conventions of theatre photography up until then, so it was inevitable that he would influence those who came after him.”

For director Katie Mitchell, Kyncl’s modus operandi was being “a physical actor, where he would slide on to the stage and follow the action and actors to get as close as he could to the emotions in play”. Mitchell considers him “the greatest theatre and opera photographer of his generation”.

Kyncl died in 2004. His widow, Alena Melichar, described by Hands as his “inspiration, supporter and still centre”, believes his youthful experiences of photojournalism in stressful circumstances informed his theatre photography.

She says: “Ivan approached the task as if covering an assignment in a fast-moving news story. Contrary to the unspoken role that photographers undertake – placing themselves mid-auditorium with a tripod – Ivan bounced backwards and forwards, leaping over stalls, dashing into the wings, zipping up to the dress circle, and even going on stage.”

Ivan Kyncl: In the Minute will be at the V&A’s Theatre and Performance Galleries until July 7. Visit vam.ac.uk for details

If you’d like to read more stories from the history of theatre, all previous content from The Stage is available at the British Newspaper Archive in a convenient, easy-to-access format. Please visit: thestage.co.uk/archive

Latest Obituaries

More about this organisation

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99