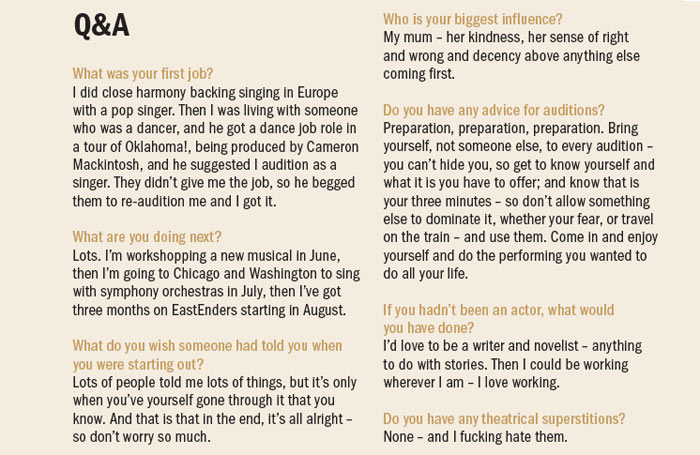

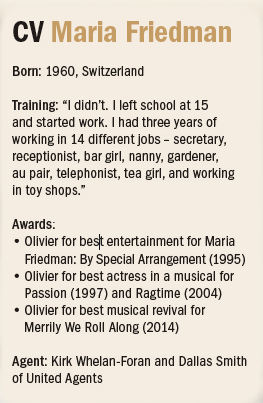

The Big Interview: Maria Friedman

A lot has happened to Maria Friedman in the decade since she last originated a role in a new musical and took it to both the West End and Broadway. That was Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Woman in White, and at the very moment when she should have been on top of the world, her world came crashing down around her.

Just three days after starting Broadway previews in October 2005, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Two days later, she went under the knife to remove the lump – and after missing just seven performances, was back on stage. The show opened on schedule two weeks later. “You just get on with it,” she told me when I last interviewed her in 2008.

Just three days after starting Broadway previews in October 2005, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Two days later, she went under the knife to remove the lump – and after missing just seven performances, was back on stage. The show opened on schedule two weeks later. “You just get on with it,” she told me when I last interviewed her in 2008.

And she went on to say then: “It’s never as bad for the person concerned as it is for the people around them, actually. I had the most amazing team of medical people, I was surrounded by family – my sister Sonia was producing the show, my boyfriend flew in immediately to join me and stayed with me the whole time, and my children were both with me.

“I was very much blanketed with a lot of care, so it was very warm and loving. And my prognosis was incredibly good. The treatment is ghastly, but it is not nearly as ghastly at that moment when you are waiting to find out how bad your cancer is. They looked at me straight in the eye and said I was going to be okay – I was as lucky as you can be.”

And what would be a transformative moment in anyone’s life has led to changes in her life since then. That boyfriend – actor Adrian der Gregorian – is happily now her husband. Professionally, Friedman is now a highly sought-after concert and cabaret performer, with symphony orchestra engagements booked in Chicago and Washington DC in July. She’s also performed theatre roles such as Mrs Anna in The King and I and Mrs Lovett in Sweeney Todd, but only in limited runs in arena and concert productions at the Royal Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall respectively.

Her television acting career – which saw her achieve some fame back in the early 1990s when she starred in TV’s Casualty – has come full circle. She now plays the recurring role of Elaine Peacock, the mother of established character Linda Carter, in TV’s EastEnders. But most significantly, perhaps, because it is a relatively new skill, has been her development as a theatre director – first of the Olivier-winning production of Sondheim’s Merrily We Roll Along and now of Cole Porter’s High Society, which has just opened to rave reviews at the Old Vic.

“I’d never, ever thought of being a director,” she tells me now. But when she was asked to direct a private second-year student production of Merrily We Roll Along at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, she discovered something: “I did it with two casts – we had a different one for each act – and no costumes and for no audience. But it felt like a very natural thing to do, probably from years and years of looking at scripts and working out my part within them.”

It’s a show she had first appeared in at Leicester Haymarket back in 1992 when she played Mary Flynn, part of the central trio whose long and eventually destroyed friendship it charts. “But you don’t actually know a show well when you’re in it – you only look at it from your character’s perspective. I was really surprised to find that other characters had bigger parts than mine. I’d seen Merrily from Mary’s point of view only, but then you read the script and realise it’s actually told from Frank’s point of view.”

Nor, she points out, do you ever get a view of the complete production as a performer. “You never get to see the set or the lighting, for example. Actors are sometimes really confused with good or bad reviews, because they don’t know what they’re in. They can judge it a bit from the smell of the audience, but they don’t know how beautifully they’ve been lit – or how badly.”

There is, she adds, “an enormous amount of trust that has to go on between an actor and a director”, as the latter provides the eyes and ears for an actor to watch and listen to their work.

Working with students at Central taught her some of this. That might have been that, but for the fact that two uninvited guests came to see it. “Sonia [Friedman, her sister] and David [Babani, artistic director of the Menier Chocolate Factory] popped in without being asked. Our musical director Michael Haslam had tipped David off that he should see it, so he and Sonia snuck in uninvited. None of the cast was allowed to have friends or family there, only teachers, so there would be no pressure on them – but then suddenly they had Sonia and David watching them, two of the most powerful people in musicals.

“The next day, Sonia rang up and said: ‘Which designers do you like?’ I replied, ‘I don’t know, I don’t go out enough.’ She said that I should do it in the West End. But then she decided it was better that she wasn’t directly involved in my first full directing job, to give me a fair chance to do it on my own without her reputation getting in the way. So I did it at the Chocolate Factory, we got five-star reviews, and then she swooped in and took it to the West End and allowed me to get an Olivier for it. That’s my darling little sister.”

In The Guardian, Michael Billington called it an “astonishing directorial debut”, but she bided her time before returning to the directorial reins with High Society at the Old Vic now.

Like Julia McKenzie, also an established Sondheim performer of shows that stretched from Side by Side by Sondheim and Follies to Sweeney Todd, who turned to directing with shows such as Putting It Together (the sequel to Side by Side) and Stiles and Drewe’s Honk!, I ask if it is a natural progression to direct?

“It is for women, because where are the parts after a certain age? If you’re a creative person, and you love theatre and you love being among companies, there are parts like Aunt Eller [in Oklahoma!] available to you, but what else? There’s nothing wrong with Aunt Eller, but there’s a limit. But I love the theatre, I just love the collaborative thing. I don’t do it that often, but I miss it when I’m not doing it; and when I miss it hugely, I have to find another vehicle to go back to it with.”

The timing – and opportunity – have proved right for her to now do so with High Society. How did it come about?

John Richardson, a producer at the Old Vic, had taken her to dinner after he’d seen Merrily We Roll Along, and asked her what she’d like to do next. “He told me they’d like to do a musical in the round,” she says, referring to the theatre’s occasional new configuration, “and asked me to come up with something.

“I was very flattered, but you don’t take stuff like that at face value. So I didn’t pursue it and he didn’t call me back. But it turns out he was sincere, and then I got another call: I was on holiday with my husband and family in the south of France and was beside the swimming pool when he called and asked, ‘What do you think about High Society?’ I thought he was asking me to audition and I said, ‘Please send me the script, I’d love to come and interview for it.’ But he said no, he wanted me to come and direct it.”

It was again relatively unfamiliar territory. “I’d seen the movie, but I’d never seen it onstage. And my initial thought was: Why do I actually want to do something about posh people? That’s not where I live – I live in conflict and fallibility and the human condition.

“Then up popped this script and I could see that it actually had all that. It was about people prejudging each other, not giving each other a chance, not understanding how essential it is to be honest with yourself and honest with each other. Everyone was hiding something and everyone had something to learn. And at the centre of it is this wonderful creature who is born into privilege, has all these expectations of herself and others, and is constantly trying to change herself and be the best she can, and I got intoxicated with her.”

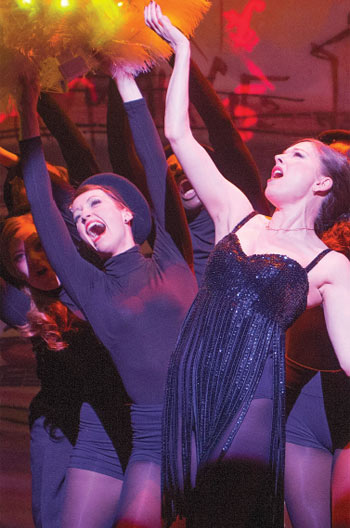

That character is Tracy Lord, famously played in the 1956 film of High Society by Grace Kelly – and a tough act to follow. “I knew we’d need someone who is a brilliant actress, intoxicating and beguiling.” The plot revolves around a serendipitous day when Lord’s former husband re-enters her life just as she’s about to marry another man, while a visiting journalist also catches her attention: “All must be plausible and possible for her, but each supply something she hasn’t got herself. All these privileged, clever men can have any pretty woman they want – but what they can’t have is this extraordinarily intelligent, fierce, fast-thinking, humorous, manipulative and deeply able human being.”

Perhaps Friedman is itemising her own qualities, although she’s too naturally modest to suggest as much; but it was an equally serendipitous event that first introduced her to the person who would fit that bill: Kate Fleetwood – whose credits include Lady Macbeth to Patrick Stewart and who also happens to be married to director Rupert Goold, who directed Made in Dagenham in which Friedman’s husband starred.

“We met for the first time at the opening night [of Made in Dagenham], and there was something so exquisite and beguiling about her, with vulnerability and strength pouring out of her. I thought, ‘You have no idea of this, but I think you’re my Tracy Lord’. I had no idea if she could sing or not, but I operate on instinct.”

That instinct proved entirely accurate. (Fleetwood was also in the original London cast – and now film – of the musical London Road). But if she’d solved one central riddle of getting High Society to work on stage, there was possibly an even bigger challenge to face in producer Richardson’s original requirement to have it done in the round. “First I chose Merrily We Roll Along, a never-successful musical, then High Society, also never previously successful on stage, and put it in the round – what does that say about me? Does the word masochist come into it? I can’t pretend it has been easy – technically, it is unspeakably difficult. I’ve got to make sure that the story is available at all times to the whole audience. But I’ve loved the challenge. It’s like a puzzle – but I adore puzzles and games.”

And it has been duly rewarded by reviews like Ian Shuttleworth’s in the Financial Times, who noted: “Maria Friedman’s move from musical theatre performance into direction is only enhanced by her touch here. Like that other musical actor-turned-director Daniel Evans, she takes care to ensure a constant yet unforced vivacity onstage.”

And it has been duly rewarded by reviews like Ian Shuttleworth’s in the Financial Times, who noted: “Maria Friedman’s move from musical theatre performance into direction is only enhanced by her touch here. Like that other musical actor-turned-director Daniel Evans, she takes care to ensure a constant yet unforced vivacity onstage.”

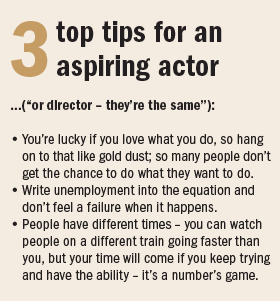

Shuttleworth could be describing Friedman’s offstage appearance too. Yet she claims not to be ambitious: “I don’t sit there with an urge to do anything in particular – I just like to see what arrives on my desk and is interesting. I have no yearning, burning desire to do particular roles, either.”

What about Momma Rose in Gypsy? “If it had arrived, of course I would have done it, but Imelda [Staunton] got it, and if someone has already done something brilliantly, I can leave it. I don’t feel the world is waiting for my Momma Rose; I don’t think anyone gives a shit whether I do it or not.”

She admits that she’d love to play Sally in Follies, and says: “I’d always play Mrs Lovett [in Sweeney Todd] anywhere, but I get to do concert versions. I have to be very grown up about the fact that if Emma Thompson or Maria Friedman are going to be up for Mrs Lovett, she is going to get the job,” she says, referring to the recent English National Opera production. “That’s the way the world goes. If I spent my life worrying that I’m not famous enough, it would kill me.”

As it is, she’s far happier instead to be balancing a career of many different disciplines: “I earn enough doing 20 to 30 concerts a year to give me a life and give me the chance to do television, directing, singing and spending time with my family – it’s a better balance at my age.

Opinion

More about this person

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99