Matthew Warchus: ‘I don’t have Spacey’s star power – all I have to offer are productions’

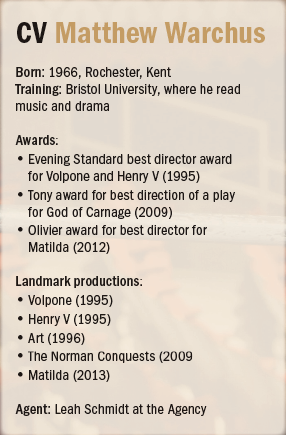

Like most British theatre directors, Matthew Warchus began his directing career in the subsidised sector, first as an assistant at the Bristol Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company, then as an associate at West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds, before regularly directing at places such as the Royal Shakespeare Company, National and Donmar Warehouse.

But he has also segued effortlessly towards the commercial arena, from his West End debut as director of a production of Much Ado About Nothing for producer Thelma Holt that starred Mark Rylance and Janet McTeer at the Queen’s Theatre 22 years ago, to the international success of Yasmina Reza’s Art that he directed the English-language premiere of at Wyndham’s in 1996 (with a cast that originally featured Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay and Ken Stott). “Art took up a lot of time,” he says. “It ran for seven years in this country and I also did it around the world – it gave me a lot of opportunities and cleared my overdraft.”

But he has also segued effortlessly towards the commercial arena, from his West End debut as director of a production of Much Ado About Nothing for producer Thelma Holt that starred Mark Rylance and Janet McTeer at the Queen’s Theatre 22 years ago, to the international success of Yasmina Reza’s Art that he directed the English-language premiere of at Wyndham’s in 1996 (with a cast that originally featured Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay and Ken Stott). “Art took up a lot of time,” he says. “It ran for seven years in this country and I also did it around the world – it gave me a lot of opportunities and cleared my overdraft.”

Warchus is sitting in the backstage dressing room that has been converted into an office inside the Old Vic, a theatre he has recently officially taken over the stewardship of from Kevin Spacey.

He is amiable but naturally reserved, yet quietly confident and definitely in charge. When he announced his first season for the Old Vic back in April, which kicks off this month, he said: “After 25 years of freelance directing, I unexpectedly find myself running my favourite theatre in the world.” Sitting in the building today, he says: “I have said no to the opportunity of running a theatre over and over again over the last 20 years, and if another theatre had offered it, I’d still have been quite likely to say no. But there’s something about the Old Vic that just hooked me.”

When I press him further about how he came to do this, he replies: “I’m not sure what the tipping point really was. I’d always resisted it because it felt claustrophobic and I didn’t want to be trapped in one place. There were lots of other contrasting opportunities and things I was interested in doing. I was also always wary about the amount of other obligations that you have when you run a building that distract you from just creating a piece of work in the best possible way you can. However, in recent years I got quite interested in the producing side of things – I was starting to raise bits of money for some of the productions I was directing, so I’d meet investors and I started to set up a company by which I could put some profits from shows into a commissioning fund to commission new work myself.”

Groundhog Day, a new musical based on the 1993 film of the same name that features in his opening season at the Old Vic, is a project he had the idea for himself, and developed on spec, without any commercial producers on board (although that’s now changed, and it has already been announced for a Broadway opening in 2017). It reunites him with Tim Minchin, the composer of his award-winning production of Matilda that is now simultaneously a West End and Broadway hit and has just opened in Sydney.

“Tim took a bit of convincing – he wanted his next musical to be something new, not an adaptation of anything, but I leant on him heavily to consider it, and he quite quickly saw what I knew it could be.”

Warchus is refreshingly candid about the fact that Broadway plans have already been announced for it: “It feels very hubristic and anything can happen, but it came about directly as a result of our most recent workshop, when it felt like it was in very strong shape and like a Broadway musical.”

The Old Vic will, in effect, be like a regional tryout – London instead of Philadelphia or Boston. It is part of his specific mission for the Old Vic that shows might be nurtured there for a life beyond it – he’s programmed seven shows across the first year of his regime, instead of the four the theatre used to do.

“What you can do for the first time is transfer shows more easily; when they already run here for 12 or 14 weeks, they became a risk to then put into the West End. But now, after running for only six weeks here, if they’ve gone well and the casts want to, they can be transferred before they’ve exhausted their audience.”

He’s got West End and Broadway producers Sonia Friedman and Scott Rudin on board to do so. “That’s the reason I turned to them – there’s an opportunity here and I’d like their expertise standing by to exploit it.”

They’ve also contributed a lump sum to the theatre as an advance towards its operating costs in exchange for those future commercial rights. It’s part of changing the entire producing model and profile of the theatre. “The reasons for making the change were both artistic and commercial. Artistically, I wanted people to see that there were a wealth of different kinds of opportunities for great nights in the theatre that were going to be happening at the Old Vic.

“With four plays a year, having to programme for things that would run for 12-14 weeks in a 1,000-seater theatre you had to play quite safe – there had to be something quite familiar about the shows. But if we have shorter runs and only need to fill the theatre for five or six weeks, it becomes less demanding to fill it and you can be more adventurous in the programming. In a single year we can have a hugely diverse repertoire, form a family orientated show for all ages to a piece of musical theatre, a dance piece, a revival of a classic and new work, plus more envelope pushing work – I’d put O’Neill’s The Hairy Ape, that Richard Jones is directing, in that category.”

He credits Jones, whom he calls “my favourite director in the country”, as one of his greatest theatrical influences from productions that Jones directed at the Old Vic under Jonathan Miller’s regime in the 1980s of Ostrovsky’s Too Clever by Half, Corneille’s The Illusion and Feydeau’s A Flea in Her Ear.

It is precisely that kind of theatrical excitement and innovation he wants to bring back to the Old Vic. “Kevin [Spacey] saved the Old Vic from demise – it almost stopped being a theatre and he did a very good job at rescuing the building and shining a big light on it, reminding people what a grand old theatre it is and what great nights in the theatre have happened here. The job now is to consolidate that and to continue to establish the Old Vic as an indispensable producing theatre in London, and to really protect its future. Part of that is establishing it as a strong artistic producing theatre – like a turbo-charged regional theatre that does a whole range of work on a scale that you don’t usually see in London. Lots of other producing theatres in London are much smaller – but with 1,000 seats, we’re working on a real populist scale.”

He’s had his own first-hand experience of what that means here, when he directed Ayckbourn’s The Norman Conquests (that subsequently transferred to Broadway’s Circle in the Square) and Mamet’s Speed-the-Plow that starred Spacey himself and Jeff Goldblum at the theatre. Commercial opportunities for the latter were scuppered when a separate Broadway production starring Jeremy Piven was produced. Piven (in)famously withdrew from that show citing mercury poisoning from eating sushi, and today Warchus quips: “Some people thought I’d poisoned him so I could get our production there.”

For The Norman Conquests, Warchus was instrumental in getting the venue reconfigured into an in-the-round theatre, when it is called the CQS Space after its commercial sponsors. He explains: “I like to say that the Old Vic is really my two favourite theatres now. It’s a really brilliant proscenium arch theatre with a fantastically huge stage, in which the relationship between the stage and the auditorium is a beautifully balanced design that gives the performer a lot of authority and power. And the in-the-round module is a wonderfully successful format as well. Most in-the-round theatres are about 300 seats, but this one manages to be a wrap-around 1,000 seats, which makes it a wonderful epic space yet it is also very engaging. I like both of those formats, and it does both of them really, really well.”

The opening production of his regime is a new play by Tamsin Oglesby called Future Conditional that is using the basis of the in-the-round configuration. “But we’ve taken out the side portions, so in effect it is a traverse, which has never been done before.” The play, which revolves around current British schooling and features a cast of 23 young performers as well as Rob Brydon, is, he says, “a rock’n’roll production, and it benefits from having the looseness of this setting”.

“It’s a play,” he says, “I’ve funnily enough been carrying around in my pocket for a couple of years. It was sent to me by Tamsin – it had been commissioned by the National but they were indicating that they were not going to do it, and I liked it immediately and felt it should be done somewhere. So I set about trying to find ways of doing it at different theatres, including the West End. And it dawned on me straight away when I got this job that it was a good one to do here.

“It’s a play,” he says, “I’ve funnily enough been carrying around in my pocket for a couple of years. It was sent to me by Tamsin – it had been commissioned by the National but they were indicating that they were not going to do it, and I liked it immediately and felt it should be done somewhere. So I set about trying to find ways of doing it at different theatres, including the West End. And it dawned on me straight away when I got this job that it was a good one to do here.

“There’s something right about starting with a brand-new play, and also one that speaks to young people as well as adults and has a lot of young people in it. The word ‘old’ in Old Vic is a little bit of a burden – I use it to remind myself to always think of the opposite, and the two opposites of old are ‘new’ and ‘young’. They’re important watchwords to me.”

Of course, the Old Vic has its own competition just down the street in the form of the Young Vic that offers just those aspects. “Straight away I started a dialogue with [Young Vic artistic director] David Lan – we really should be like brother and sister as theatres, and ideally there’ll be an equivalent vibrancy about this theatre,” he says, referring to the Young Vic’s current status as one of the most electrifying theatres in London. “The difference, I hope, will really be about the different sizes of our theatres.”

Warchus has given himself a tough act to follow if he wants to repeat the success of the Young Vic, but he also has a great calling card: his own track record as a director. “All I’ve got to offer is productions. I can’t walk out on the stage and fill the theatre the way Kevin did with star power. My contribution will be productions, so it makes sense to do a bunch of them.”

He is directing four shows out of the opening slate of seven, which he says is “too many – that’s not how it should be”. He adds: “I should be directing two shows a year and making room for other directors I love. But for my first year, I was scrambling to get a season together. No freelance director goes around with a year’s season already figured out in their heads just in case they need to programme one.

“I approached a lot of directors trying to find out what people might want to do, but availability was a big issue with the people at the top of my list. I was already committed to a production of Ibsen’s Master Builder on Broadway with Ralph Fiennes, so I said to him and to Scott Rudin who was producing it that I’d like to start it at the Old Vic and make it a centrepiece of the season, and they agreed.

“I was also already attached to Groundhog Day, so those were two things I was unavoidably directing. Then I was told that it was crucial that I directed the first show in the season, and it would be weird if I didn’t, so that’s why I’m launching with Future Conditional. And I’m also directing The Caretaker with Timothy Spall – I discovered that he was interested in doing it, and it’s a play very close to my heart because I’ve never directed it and my father was in it – he was a successful actor before he became a vicar and had played Mick, which I’d seen photographs of him doing. Tim was very keen on me doing it, and I had sentimental reasons to do so, so I decided to do it rather than risk losing it to another theatre.”

The season is completed by Jones directing The Hairy Ape, a dance piece called Jekyll and Hyde that is being devised, directed and choreographed by rising star Drew McOnie, and a Christmas show, Dr Seuss’ The Lorax, directed by another young director Max Webster. That reflects another keen interest of Warchus’: to support and nurture new talent, just as he was given a head start by Jude Kelly at West Yorkshire Playhouse inviting him to be an associate there and direct mainstage shows like Peter Pan and Fiddler on the Roof when he was still in his 20s.

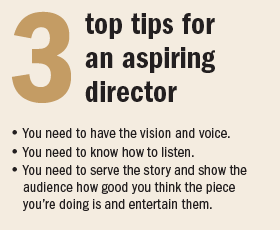

“Being a parent in real life [he has three children with his actress wife Lauren Ward], and I suppose as I was getting older, I felt that parental thing of wanting to help other people on with their projects. It’s a very different kind of creativity, but it also feels very creative to put people and projects together that are not necessarily for me to direct. I want to help up-and-coming directors – I very much remember that enormous faith that was placed in me by Jude, and I think that if you put a big responsibility on the right person’s shoulders you get better results than if you put a small responsibility on them.”

“Being a parent in real life [he has three children with his actress wife Lauren Ward], and I suppose as I was getting older, I felt that parental thing of wanting to help other people on with their projects. It’s a very different kind of creativity, but it also feels very creative to put people and projects together that are not necessarily for me to direct. I want to help up-and-coming directors – I very much remember that enormous faith that was placed in me by Jude, and I think that if you put a big responsibility on the right person’s shoulders you get better results than if you put a small responsibility on them.”

Now he’s got the huge responsibility of running his own building for the first time, he’s also trying out a brave new economic model too. “There’s a big financial challenge in paying for it all. We haven’t just divided out our existing four-show budget into seven shows, but we’ve upped it to seven full budgets. So the costs are higher, but in theory it is possible that when audiences get used to what’s going on at the Old Vic, they’ll realise that they only have a more limited time to see a show so average attendance performance should go up, I hope.”

Warchus also has a longer-term ambition across the five years he has signed up to run the Old Vic for, and that’s to raise the money for the redevelopment plan that’s already been drawn up and modelled, “for the theatre to become a strong physical entity for the next 50 years, and to hand on a strong artistic signature when I leave, too.”

Opinion

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99