Matthew Bourne: ‘You can always do better and find new ways to be creative’

Michael Flatley may have dubbed himself Lord of the Dance, but really the title belongs, on the British stage at least, to Matthew Bourne.

This weekend, Bourne is to receive The Stage award for outstanding contribution to British theatre. He has certainly earned it – and some. New Adventures, the company he founded and runs, is a resident company at Sadler’s Wells, performing an extended annual Christmas season, while also giving more performances than any other British dance company on tour in the UK and around the world.

This weekend, Bourne is to receive The Stage award for outstanding contribution to British theatre. He has certainly earned it – and some. New Adventures, the company he founded and runs, is a resident company at Sadler’s Wells, performing an extended annual Christmas season, while also giving more performances than any other British dance company on tour in the UK and around the world.

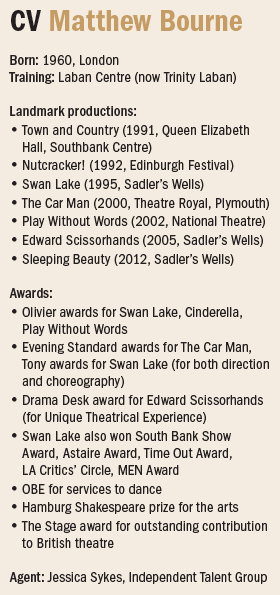

He is also widely known for his choreographic work in musical theatre. Next week, the stage version of Mary Poppins – which he co-directed and co-choreographed in the West End and on Broadway – is being revived at Leicester’s Curve, prior to an extensive national tour.

When I meet him at the Islington home that he shares with his partner Arthur Pita, who is also a choreographer, and their bouncy new six-month old puppy Ferdinand, he quips that when he was told he was getting the UK Theatre award: “I thought I’d already got it, as the company won the outstanding achievement in dance award at the 2011 UK Theatre Awards. But this is a slightly different, bigger, wonderful thing, and it’s fabulous, coming from an organisation like this because it is about touring theatre, which is what we do and have done for many years.”

The recognition of his contribution is deserved: he has stretched and popularised modern dance as few others have, with distinctive versions of classical ballets, from Nutcracker! (as his version is dubbed) and Swan Lake to Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty, and original dance works based on other literary or cinematic sources including Dorian Gray (based on Oscar Wilde’s story), The Car Man (based on the film The Postman Always Rings Twice, set to Bizet’s score for Carmen), Edward Scissorhands (based on the Tim Burton film), Lord of the Flies (based on the book by William Golding) and Play Without Words (based on the film The Servant).

These, and other shorter works such as Spitfire, Town and Country and The Infernal Galop, have been created across a 28-year period since he formed his first company in 1987.

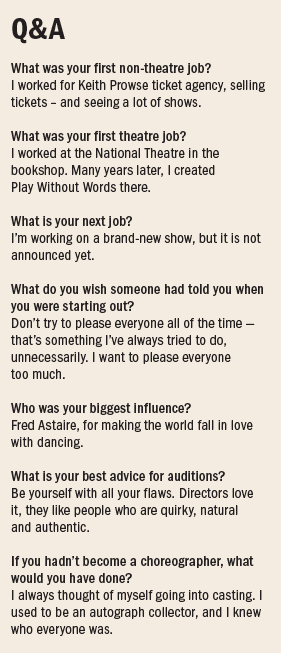

Now 55, Bourne didn’t train to become a dancer until he was 22. “I crammed it all in a bit later,” he acknowledges; “I could have had an even longer career at this point if I’d started sooner.” But he feels it was actually an advantage to have started later now: “It was a great thing for me – especially in dance, things can be so singular and you’re on one pathway from a very early age that all your references are dance references. But I’d had this very eclectic upbringing – I was born and brought up in London, and I saw a lot of theatre as my parents loved it and so took me quite a lot, and I saw lots of different things and travelled a bit. All of that goes into my work now. I don’t think that would have happened if I’d started out in a ballet school.”

Instead, he was an instinctive dancer from an early age: “Everything I learnt was from watching – I saw a lot of movies, and I’d come home from the cinema and put on a show and recreate what I’d seen. From the age of about four onwards I was always putting on a show, and I wanted people to come and watch it – I wanted an audience. So that desire seems to have always been there. Then I had to find a medium in which to express what I could do.”

It turned out to be contemporary dance. But he had no formal dance training until he went to the Laban in 1982 to study dance theatre and choreography. He was a little bit older than his peers, who were only 18 or 19: “It wasn’t a massive age difference, but I felt it. I was there because I really wanted to be there, though, rather than just going there because it was the next thing to do. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with it – I thought I was a bit late to begin a professional dance career, and I thought that maybe I’d end up writing about dance.”

One of his teachers at Laban was Alastair Macaulay, now chief dance critic of The New York Times, who helped him to acquire a critical eye when they went to lots of shows together. They also shared a passion for the work of Fred Astaire, “and it made me look at that work in a different way”.

After graduating, Bourne spent a further year with the college’s performance company called Transitions: “It was good to know how a company might work, and to start making relationships around the country.”

Out of that came Bourne’s first iteration of a touring company: “A group of friends who were in that company decided that we should form our own company. Several wanted to choreograph and we all wanted to perform, and we picked a couple more who were graduating that year and formed a collective. I wasn’t the sole director – there were three of us, the others being Emma Gladstone [now artistic director of Dance Umbrella] and David Massingham [now artistic director of the Birmingham-based DanceXchange], so we all still have prominent roles in the dance world.”

But the company was entirely unsalaried, and Bourne supported himself, both before his training, throughout it and after it again, by working front-of-house at the National Theatre, mostly in the foyer bookshops.

“I was there for nine years in all – two years pre-college, right through it, and another three years after it – and became a fixture. I was one of the longest-serving people there, and they were wonderful years. The great thing working there was the turnover of shows and I got to see so much and so many great performances – I have many great memories of seeing things more than once, and that’s how you make them go into your brain and you remember them.”

He also observed different approaches to acting: “I learnt a lot about acting watching actors perform. When I first came into the building, Guys and Dolls was being performed – everyone was singing in the corridors – and Julie Covington was a good example of someone I used to watch. She’d never do the same thing twice, and I only knew that because I saw her a lot. Others would get their show and that would be that. I prefer the more fluid approach.”

Meanwhile, he started creating his own short works, including Town and Country, which won the Barclays New Stages Award and gave the show a week of performances at the Royal Court. “That was very significant for us, because it brought us a whole new audience and introduced me to a different world beyond the dance one. It also got me the gig to create Nutcracker! at the Edinburgh International Festival in 1992, commissioned by Opera North. Nutcracker!, in turn, led to Swan Lake. I’d never have thought of choreographing a full-length ballet to an existing score before that, though I went to them and enjoyed them. Nutcracker! gave me the bug for it, and I thought I could do it with so many other pieces, but I wouldn’t have got the opportunity to do Swan Lake without that.”

Swan Lake was created at the old Sadler’s Wells, where – at its first performance – something else important happened. “At the interval, Cameron Mackintosh pinned me against a wall, as he does, and said to me, ‘This must be in the West End!’, and then he helped to make that happen, moving it to the Piccadilly.”

It would become the longest continuous run of a ballet production in West End history, and that presented its own problems: “It was also very hard work trying to make it work. We were a group of people who were never used to doing that many shows a week – dancers just don’t do it usually. We know how to make it work now, but we didn’t then, and we needed more people in the cast so that they could rotate roles, and we needed a physio there all the time to keep people fit and happy. But we got an amazing reaction every night, so that made it worthwhile.”

It would also subsequently transfer to Broadway after a run at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles first. “Gordon Davidson, who runs the Ahmanson, took a very bold chance on us, and wrote to his subscribers offering them their money back if they didn’t like it.”

Then came Broadway, and more lessons were being learnt: “If it happened now, it would be a different story, but I was told not to call it a ballet, so the whole way of marketing it was very complex. Because Cameron was the most famous person attached to it, he did a lot of interviews, and said it’s more like a musical. But actually it was a ballet.” Nevertheless, Bourne himself won two Tonys – for best direction of a musical and best choreography – so perhaps the mislabelling worked.

The clear commercial appeal of Swan Lake also created problems of its own – those of success: “There was a big shift in perceptions around our company and what we do and how other companies should operate. At the time that Swan Lake became a commercial success, there was a perception that we therefore didn’t need funding,” as they’d been getting from the arts council. “But it was very expensive to do that show.”

In-between the West End and Broadway runs of Swan Lake, Bourne also created a second commercial ballet in Cinderella that ran in the West End, again with Mackintosh co-producing, and he admits now: “It needed a lot of work. When we did it again, I made a lot of changes.”

In-between the West End and Broadway runs of Swan Lake, Bourne also created a second commercial ballet in Cinderella that ran in the West End, again with Mackintosh co-producing, and he admits now: “It needed a lot of work. When we did it again, I made a lot of changes.”

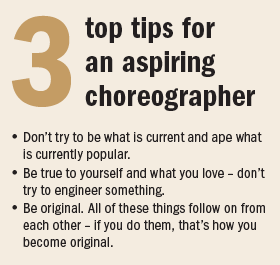

But then he’s not shy of revisiting past work and improving it: “I’ve always felt like we have a rep and are building one. A lot of choreographers like to create something then they don’t want to do it again. But for me you can always do better and find new ways to be creative with a piece – there’s no doubt that they’ve always got better when they come back. Every one has had a very big overhaul when they come back for the first or second time.”

This Christmas he’s duly bringing back Sleeping Beauty to Sadler’s Wells, before an international tour next year, following the summer return of The Car Man. That show’s triumphant sell-out run was sadly overshadowed by the death of one of its principal dancers, 38-year-old Jonathan Ollivier. He was killed in a motorcycling accident on his way to the theatre on the last day of the run and the final performance was cancelled. “It was very upsetting and a big loss,” says Bourne.

On a happier note, he points out that Zizi Strallen, who danced in The Car Man, is now about to star in the title role of Mary Poppins on the road: “What a year for her – she’s incredibly versatile and the two roles couldn’t be more different.”

And it leads to a striking observation: “An interesting thing has happened with dance training in general: training in musical theatre colleges has improved enormously dance-wise over the last 10 years, while contemporary dance training has shifted to become a little more inward-looking, where everyone is a creator so they don’t want discipline or rules. The sort of performers I want to work with are musical theatre and ballet performers, because they’re all about playing out and generosity. So someone like Zizi can come into the company and fits in extremely well – she’s a great dancer and a great actress – and then she can go off and do Mary Poppins.”

Bourne has enjoyed his musical theatre work, too, and says he’s particularly proud of My Fair Lady, which he choreographed for director Trevor Nunn at the National, which subsequently transferred to Drury Lane: “I loved doing the Ascot Gavotte.”

Musical theatre, of course, is about collaboration: “I enjoy collaboration, and we had a lot of collaboration on Mary Poppins – there was a co-director and a co-choreographer alongside me, and there were also two sets of songwriters and two sets of producers. It was the most co-show ever!”

He was particularly pleased to work with Richard Eyre, whose production of Guys and Dolls at the National had made such an impact on him: “I’ve been so lucky with the directors I’ve worked with – I’ve learnt so much from them and taken it back into my own company.”

Now, he’s aware of passing the torch himself to others, like Drew McOnie, a one-time dancer in New Adventures who is now making great choreographic strides of his own with shows such as In the Heights, which reopened at the King’s Cross Theatre this week after premiering at Southwark Playhouse last year.

Now, he’s aware of passing the torch himself to others, like Drew McOnie, a one-time dancer in New Adventures who is now making great choreographic strides of his own with shows such as In the Heights, which reopened at the King’s Cross Theatre this week after premiering at Southwark Playhouse last year.

“I’ve been a big champion of his from the beginning. He won’t do the norm. When he did The Producers at Arts Ed, he didn’t use anything from the original but had his own ideas about everything. That’s the way choreography should be – you have to have your own language with each piece.

“He’s brilliant, I think, probably the best – I’ll have to watch him, won’t I?”, he jokes, looking to his own laurels instead of just resting on them.

Opinion

More about this person

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99