Kenny Wax: ‘I’ve done every job from tour guide to follow-spot operator’

A couple of weeks ago, Kenny Wax had his biggest week in the West End to date, opening three shows in the same week there. On August 3, he brought real-life father and son James and Jack Fox to play father and son in the stage version of Dear Lupin at the Apollo; three days later, on August 6, he opened The Three Little Pigs, a new children’s musical by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe, at the Palace Theatre, to play daytime performances for a month; and the day after that, his Olivier-nominated production of Hetty Feather, adapted from the book by Jacqueline Wilson, officially returned for a summer West End run at the Duke of York’s.

A couple of weeks ago, Kenny Wax had his biggest week in the West End to date, opening three shows in the same week there. On August 3, he brought real-life father and son James and Jack Fox to play father and son in the stage version of Dear Lupin at the Apollo; three days later, on August 6, he opened The Three Little Pigs, a new children’s musical by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe, at the Palace Theatre, to play daytime performances for a month; and the day after that, his Olivier-nominated production of Hetty Feather, adapted from the book by Jacqueline Wilson, officially returned for a summer West End run at the Duke of York’s.

They joined the already-running summer return of The Gruffalo, playing a phenomenal schedule of 18 daytime performances a week at the Lyric (with two separate casts to accommodate the demand), and his Olivier award-winning hit comedy The Play That Goes Wrong, which is about to go into its second year at the Duchess. He also has two kids’ shows on the road – The Tiger Who Came to Tea and Room on the Broom. If that weren’t enough, his Olivier award-winning production of Top Hat (which he also co-wrote under the ‘secret’ pseudonym Howard Jacques) has just finished its second UK tour before heading to Japan, with its full English company going out.

“This Christmas, I’ll have 10 productions on around the country – which could go to 11 if one more works out,” says the affable Wax, sitting at his desk in his Shaftesbury Avenue office. The confirmed ones are seven kids’ shows doing the rounds, including a Christmas run of Hetty Feather at the Lowry in Salford Quays, a brand new kids’ show based on the popular American book Mr Popper’s Penguins, the ongoing The Play That Goes Wrong and a West End season for Peter Pan Goes Wrong from the same team.

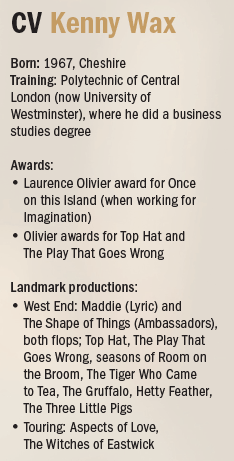

This year marks the 20th anniversary since he set up shop as an independent producer, and Wax – who is now 48 – has built up a formidable portfolio. He began his theatrical career in 1989 as an usher at Drury Lane, just as Cameron Mackintosh began as a stage hand at the same theatre, and where Mackintosh was then producing the original production of Miss Saigon.

And it was Mackintosh who offered him his first choice piece of advice as Wax sought to emulate him in other ways, too. While he was ushering, he dropped Mackintosh a letter to try to work for him. “But he told me that I needed to get more experience in the business. He said that if he gave me a job, I’d be a tiny paper clip in a huge pencil case, and I wouldn’t learn anything.”

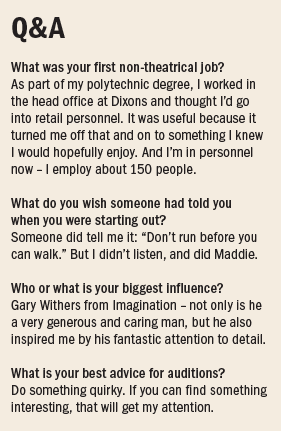

So he set about, in that accidental way that most theatre careers are made but in fact seems deliberate with hindsight, to acquire plenty of experience. He’d already done front of house; now it was time to go backstage and dip his toes into advertising and management. After working at Drury Lane for a few months, he got a job as a foot messenger at theatre advertising agency Dewynters, and after trudging the West End streets for a few months (and getting to know his way around its theatre offices), moved indoors to work in the media department, booking classified ads for clients.

He left a secure job at Dewynters, though, to realise his ambition to work on the nuts and bolts of a show, and became a runner on Mackintosh’s production of Stiles and Drewe’s Just So at the Tricycle, directed by Mike Ockrent, in 1990. All of those names had already played or would play a big role in his life.

“The reason I went into the business in the first place was that I just adored Mike Ockrent’s fantastic production of Me and My Girl with Robert Lindsay and Emma Thompson,” he says of the 1985 West End show that reclaimed a lost 1937 Noel Gay musical and restored it for a new generation. It would eventually provide the inspiration for him to do the same with Top Hat, a film that was first released two years before the original Me and My Girl.

“The reason I went into the business in the first place was that I just adored Mike Ockrent’s fantastic production of Me and My Girl with Robert Lindsay and Emma Thompson,” he says of the 1985 West End show that reclaimed a lost 1937 Noel Gay musical and restored it for a new generation. It would eventually provide the inspiration for him to do the same with Top Hat, a film that was first released two years before the original Me and My Girl.

Stiles and Drewe, too, would play a recurring role in his theatrical life for the next quarter of a century, culminating in the current West End run of their Three Little Pigs; he’s currently trying to entice them to write another show for him.

When he decided to leave Dewynters, he was told that if he left he couldn’t go back – “but it was too good an opportunity to refuse”, he says. “Young people now come through wanting to be producers, but they don’t want to do the background work first – they just want to produce.”

He would also get a job at the New London Theatre, where Cats was still running. “I was given every job in the building, from running backstage tours to operating follow spots on the show.”

Next, he went to work at London’s longest-established fringe theatre the King’s Head, then still presided over by the maverick and eccentric Dan Crawford. “I was employed as production administrator, and a general manager and assistant general manager were due to join me in a month. But when they found out that they would be paid cash in hand, and not through the books, they decided not to come. Dan said to me, ‘You look like you know what you’re doing – carry on.’ I stayed for 18 months, and during that time produced my own first show there, a concert revue called Kicking the Clouds Away.”

During that time he also co-produced The Challenge, a collaborative musical co-written by nearly 30 members of the Mercury Workshop that included Stiles and Drewe, Stephen Keeling and Shaun McKenna – names that would also turn up again in his life in the years to come.

It was staged at the Shaw Theatre, and Gary Withers, the founder of Imagination – the global events management and design company – saw it and told him: “If anyone is daft enough to do this show, I’d like them to come work for me.” So, Wax continues: “I went to be part of a new entertainment division there.” His big project there was leading an all-new West End production of the Ahrens and Flaherty Broadway hit Once on This Island into the West End, where it played in an immersive-style production at what was then the Royalty (now the Peacock). It opened in 1994 and won the next year’s Olivier award for best new musical.

But Wax was restless to have his own, original hit, and Mercury played another part in him trying to find one. “I went to the Stephen Sondheim Masterclass at Oxford, which is what Mercury came out of, and saw the presentation of a show, then called Maxie [based on a 1985 film of the same name that starred Glenn Close], that I fell in love with, by Stephen Keeling and Shaun McKenna.”

He wanted to produce it for the West End, and had to leave Imagination to do so. “I went to see Gary and he was very disappointed that I was going to leave, but it was the right thing to do and he was incredibly generous and kind.” He credits Withers as the biggest influence on his career.

Renamed Maddie, the show tried out in Salisbury and, buoyed by a very encouraging review from the Daily Telegraph’s Charles Spencer, it moved quickly to the West End’s Lyric Theatre in 1997 – and promptly flopped.

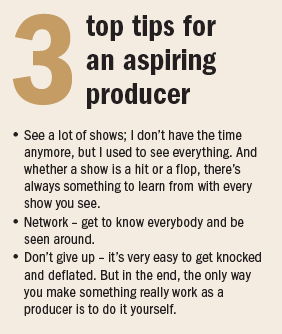

“Looking back,” Wax says now, “it was a ridiculously optimistic thing to do. I don’t love the show any less, but were I to do it now, I’d do it very differently. Part of producing is about choosing a good property and a great director and team, but choosing the journey the show goes on is also very important. It’s probably the reason why The Play That Goes Wrong has been such a success: it had this journey before I came along, at the Old Red Lion and then two stints at the Trafalgar Studios where I saw it, and then I toured it – extending it from six weeks that we booked originally to 26 weeks in the end, before it came to town.”

Shows, he believes, need that sort of journey to bed in. “When Oklahoma! and Carousel started out of town 70 or 80 years ago, they would have had a creative team who lived with the show throughout its time there. But the reality of my level of producing is that once a show is opened on tour, after about three or four days when the understudies are up to speed, the show freezes and everyone goes on to their next jobs, even if you want to make changes.

“I reckon that if a show like I Can’t Sing! had done a six or eight-week tour first, things could have been different – it had a great cast and it had the potential to be a popular hit. If it had been put in the right venues – Nottingham, Canterbury and Sheffield, say – it would have done good business, and the producer and creative team could have learnt a lot about their show. But once you’ve bared your soul to the Palladium or Drury Lane and it doesn’t quite land, you’re stuck with nowhere to go.”

Top Hat, by comparison, took a much slower route to get to the West End. It was a project that Wax himself did all the legwork on, from persuading the rights holders that this was a viable project at all and co-writing the book to assembling the cast and creative team and booking the tour dates. “This was the first time the Olivier was given to someone who didn’t exist,” he exclaims of his nom de plume Howard Jacques winning for best musical.

The idea was born one Sunday afternoon when he had some friends to tea who were big Strictly Come Dancing fans – and knew Anton du Beke a bit. “They told me was looking for a theatre project, so I thought immediately of the Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers movies and got all nine of them and watched them. Top Hat was easily the best and most appropriate and most interesting and most theatrical.”

But there was a big hurdle – the rights. “I dealt with the fantastic Caroline Underwood, who was then at Warner/Chappell, who looked after Irving Berlin’s catalogue of 1,400 songs, and we spent a few afternoons going through them to find the right songs to put into the show. And she put me in touch with Ted Chapin, who looks after the Berlin estate. I put the proposal to do the show to him, and he has a monthly meeting with the Berlin daughters who considered it but they came back saying it was not something they wanted to pursue. I thought that possibly it hadn’t been pitched properly, and if I could get my foot in the door I could get a chance to persuade them to think again.”

So he booked himself a trip to New York and asked Chapin for a meeting, ostensibly to talk about other ideas. “When he granted my wish, I told him I was there under false pretences and was only there to talk about Top Hat. As it happened, the next meeting with the Berlin daughters was scheduled for a couple of days later, so he told me to stay and meet them. But then the snow came in, and they didn’t; so Ted got them on speakerphone instead.

“I waited to be summonsed to join the call from the next room, and the first thing they said when I came on was, ‘So tell me, why have you chosen these songs?’ I was on the spot on every song in order, but I had done my homework. It was impossible to think that nobody in the last 70 years would have asked to do it on stage, and a lot of people had. But I persuaded them that if they didn’t do it now, it would be lost in 20 years’ time as no one would be alive from the age of Fred and Ginger films anymore. They had grandchildren and I’ve got children myself, and I wanted it to live on for them. They became great allies of the production, suggesting other songs too.”

There was one final piece of the rights puzzle to fit in, and that was over the film – Ted Hartley had bought the RKO film catalogue about 25 years ago, and so owned the screenplay. Chapin brokered an introduction with him, too, and he would come on-board as a co-producer of the show. And then Wax put his touring hat on to Top Hat and took it on the road.

“It was an opportunity to learn about our show, to decide what to do next, get everyone to see it who might be interested in it, and get a bit of a buzz going for the West End.” But he also lost his original star, du Beke: “We were about to sign the contract for the Plymouth Theatre Royal when Anton’s agent phoned and said he’d had a life rethink and Strictly was too important to give up, which he’d have had to have done. But someone then said they knew Tom Chambers was a good tap dancer, and he’d just won Strictly – so we sent him a script and he was immediately excited, as Fred was his great idol.”

The show now had a star, and it did get business on the road, before then coming to the Aldwych and running for nearly two years there. In its three-and-a-half-year life so far, it has taken about £50 million at the box office – but there’s still a huge risk to theatre production. Even with those figures, it has still not recouped its overall capitalisation.

By comparison, The Play That Goes Wrong, the sleeper hit Wax imported to the West End from the fringe, began (before he was involved) with a set budget of just £300. “They got the wood and timber and paints themselves and made the set for the Trafalgar Studios with their own carpentry skills. By the time we took it over, it already had half a dozen four-star reviews and some nice quotes.”

Wax attributes a big part of its success to its title. “It’s an accident but it’s a triumph, because it does exactly what it says on the tin – it doesn’t need an explanation.”

There’s now talk of Broadway next year, and meanwhile Wax has also produced its sequel Peter Pan Goes Wrong on tour, with the West End in sight this Christmas. Next, he will workshop a new play from the company in September that isn’t a ‘goes wrong’ piece but a straight comedy.

Meanwhile, he also is assembling a brand new kids’ show, Mr Popper’s Penguins, which has been designed to fit on top of Hetty Feather so the two can play side by side in the same theatres on tour and in the West End. He’d seen Raymond Briggs’ Father Christmas at Lyric Hammersmith last Christmas, directed by Emma Earle, after her agent approached him with a view to them working together. She pitched three ideas, one of which was Mr Popper’s Penguins. Wax has been intimately involved in its creation, including signing up Richy Hughes and Luke Bateman to write songs for it.

Meanwhile, he also is assembling a brand new kids’ show, Mr Popper’s Penguins, which has been designed to fit on top of Hetty Feather so the two can play side by side in the same theatres on tour and in the West End. He’d seen Raymond Briggs’ Father Christmas at Lyric Hammersmith last Christmas, directed by Emma Earle, after her agent approached him with a view to them working together. She pitched three ideas, one of which was Mr Popper’s Penguins. Wax has been intimately involved in its creation, including signing up Richy Hughes and Luke Bateman to write songs for it.

“That’s the fun – I get a lot of pleasure from being involved in songs listings and placement. I’ve seen enough musicals to vaguely understand the structure of them now.”

And he more than vaguely understands the structure of the West End now. Martyn Hayes, a long-time business associate, had commissioned a script adaptation of Dear Lupin from Michael Simkins, but didn’t know what do with it.

“I read it and adored it – so I got some touring dates, a director (Philip Franks) and then started looking at father-and-son acting combinations. We sent it to James Fox and his son Laurence originally, but Laurence didn’t think it was for him, and so James asked us to see his younger son, Jack. He hadn’t done a lot of stage work to be honest, but he was very charming and determined, he kept banging on the door. In the end, they’re a really good combination. I lost my own father a few years ago, and to see it performed by a real father and son is very moving. I’ve cried buckets watching the play.”

And that’s a producer who isn’t crying all the way to the bank, but crying for good artistic reasons instead.

Opinion

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99