Iqbal Khan: ‘I want Shakespeare to speak urgently in a 21st-century context’

Director Iqbal Khan has had a longstanding relationship with Macbeth – since he was an eight-year-old growing up in Birmingham, in fact. “We did a little production of it, me and my brothers,” he reveals. “We performed Shakespeare’s plays into tape recorders.” He smiles. “There’s a version of my Lady Macbeth in the Khan archives.” Now, 38 years later, he’s finally directing the play, for Emma Rice’s debut season at Shakespeare’s Globe. Ray Fearon and Tara Fitzgerald are the power-hungry husband and wife at its dark heart. “What grips me is the contradiction inherent in Macbeth himself,” says Khan. “He does such awful things – becomes a serial killer, a war criminal – but he’s also the most poetic character in Shakespeare.”

He continues: “Contradiction is, for me, peculiar to what Shakespeare does – he never just dramatises evil. He dramatises the awful things that good people do.” Where the Macbeths are concerned, Khan argues, “so much of what they do is rooted in their love and need for each other”.

Khan thinks big. His answers to my questions feel like offshoots from a constantly evolving framework of ideas. When we meet at the Globe – on a hot, sunny day, the theatre buzzing with visitors – he marvels at “how exciting the [rehearsal] room is. We’re being surprised by the play. It’s like I’ve never seen some of those scenes before.”

Khan has directed Shakespeare before, including Much Ado About Nothing and Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company. This is his debut at the Globe. He’s excited by its open-air space, by “the absolutely democratic way it deals with its work, its casts and its audiences”. And he relishes the “provocation” Rice has introduced to the Globe with her artistic directorship. “What are the range of theatre vocabularies we can use here?”

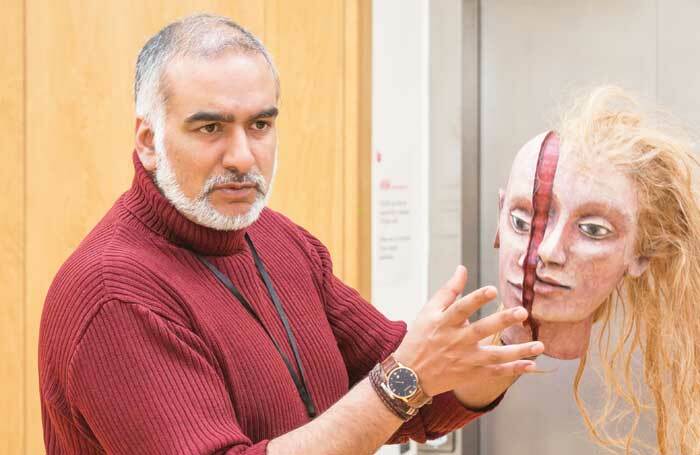

This has inspired his approach to the supernatural in Macbeth, how to convey the uncanny to a 21st-century audience. “I was keen to avoid trying to make our witches aesthetic things – creative dance things,” he says, wryly. His solution? Puppets. “There’s a moment as they’re operated where you feel like these lifeless things are alive. It’s profoundly unsettling.”

In this, Khan has embraced the Globe’s outdoor reality. “Obviously, puppets do really well in a black box, where you can control the light. But, in some ways, when you declare the strings, and yet the thing still lives independently, it’s even more uncanny. That’s very exciting, formally.”

Khan’s Macbeth will also mix amplified sound (through speakers Rice first used in her A Midsummer Night’s Dream) with “not all of the actors on mics”. And, he adds, intriguingly, “the design doesn’t try to hide that we’re in the Globe. Its history is present, as well as something more modern”. Again, it’s about responding to the audience.

For Khan, “we have to remember that, even in the most traditional spaces, the fourth wall is always missing”. A production should always take into account the world of the people watching. “If what you’re trying to do on stage is essentially make up for the loss of that wall, I think you’re fighting what theatre is,” he says. “As a director, you’re trying to serve the playwright and your audience.”

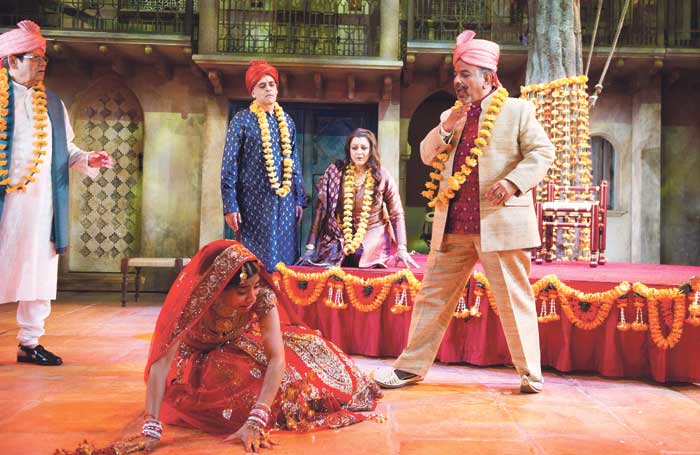

And Khan’s desire to make Shakespeare speak “urgently in a 21st-century context” has informed everything from the modern India setting of his Much Ado, to casting a black actor as Iago in Othello and, now, a black actor as Macbeth. For him, it’s about getting past complacent expectations of Shakespeare. “Boys played women. Was that verisimilitude? Did people speak this way in the street? Of course not.”

Khan believes diverse casting chimes with Shakespeare’s exploration of the truths of human experience. “There’s a richer music that can be made with a polyphony of voices,” he says. When considering Othello, he asked himself whether the traditional “black-white paradigm” truly addressed the world of his audiences or was even “the only thing that play is doing”. He felt it was “much more complicated”.

“Perhaps ironically, in making my Iago black, I made the play less about the black-and-white race issue,” Khan reflects, “and perhaps more about betrayal and other things. I liberated, I hope, the more complex powers within that play.”

Continues…

Q&A: Iqbal Khan

What was your first non-theatre job? Working in the medical records department, filing, at Fiveways Health Centre, Birmingham.

What was your first professional theatre job? Beautiful Thing at the Coliseum Theatre, Oldham.

What is your next job? Potentially a very exciting collaboration with the Globe, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the BCC Symphony Orchestra, followed by a new play in the West End, then another RSC project in early 2017.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out? It’s okay to listen to yourself.

Who or what was your biggest influence? My second eldest brother.

What’s your best advice for auditions? Think of it as your first rehearsal.

If you hadn’t been a director, what would you have been? Theoretical physicist.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals? No.

With something like Shakespeare, “your objective is to make people see it as a new play, to feel it as a new play”, Khan says. “To be radical only in the sense that you’re challenging every assumption you bring into the room, as a creative artist.”

This approach has held true for Macbeth. “I remember saying at the time [of directing Othello] that I thought it would actually be more radical if I cast a black Macbeth, and it wasn’t about his race. And that’s what I’m doing here,” Khan says.

The time when Khan feels it’s important to be specific about casting is a new play’s first outing – as with Ishy Din’s Snookered, which he directed in 2012. “That was about the experiences of four young Muslim boys, so it was very important to make that as tangible and clear as possible,” he explains. “Because you’re introducing the world of the playwright.”

Improving theatre’s diversity – from the stories it tells, to its creatives, to its audiences – is something Khan thinks deeply about. “It’s a hard one,” he says. “You can’t just snap your fingers. There’s not a lot of money, in theatre particularly, and that – along with drama schools – is where people gain the experience to hone their craft. Necessarily, those who can sustain themselves financially will last the distance.”

While Khan went to Cambridge, the working-class boy from a comprehensive school left feeling overwhelmed “by the volume of the voices there. And volume is often preferred to nuance”. Making theatre in pubs and ad-hoc spaces was a liberating contrast. It offered him the freedom of “a voice with which to entertain, to transgress, to fail, to delight”.

Aside from a proper use of subsidy to support “risky work”, he thinks that help with fees and greater training initiatives from theatres themselves, engaging the next generation, is critical to improving the diversity of the theatrical ecology.

“The more profound strategy is to look at how dramatic literature is introduced to young people in schools,” he argues. “Because that has to do with how the arts are appreciated by potential creative people, feeding their start, and about creating an appetite in potential audiences.”

To this end, Khan believes directors have a responsibility “to go to schools, to run workshops, introduce dramatic literature”. He thinks not enough advocacy is done after a press night. “I learn enormously about what makes the younger generation tick, and I can also try to communicate my love for this thing that I do, to the next generation.”

Today, Khan sees more opportunities for emerging directors, “but also many more people wanting to break into the industry”. And as theatre has become ever more expensive, more of a business – including the fringe – “every young director is hunting for that award that will give them permission to skip a few steps”.

While British theatre faces many issues, “it’s about being honest,” Khan believes. “Not promising too much, too early, but talking with real courage about the way things are.” He’s been particularly impressed by Rice’s statements on gender equality at the Globe, as well as Rufus Norris’ desire to make the National Theatre truly nationally representative.

Khan views change as a gradual process. “It’s not the fault of the Globe, or the National, say, that these buildings have acquired a certain sacred quality to them,” he says. “To make them ‘popular palaces’ – to use Joan Littlewood’s phrase – isn’t straightforward. It takes time. And it takes people like Emma and Rufus talking about theatre the way they are.”

CV: Iqbal Khan

Born: Birmingham, 1970

Training: A one-year postgraduate acting course at the Academy; then an MA in theatre directing at Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts; then the National Theatre Studio director scheme; followed by a bursary to work at Leicester Haymarket Theatre. I also received a bursary to work in Japan for a year.

Landmark productions: Landscape and A Slight Ache, National Theatre (2008), Broken Glass, Vaudeville (2011), Much Ado About Nothing, RSC (2012), Othello, RSC (2015)

Agent: None

Opinion

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99