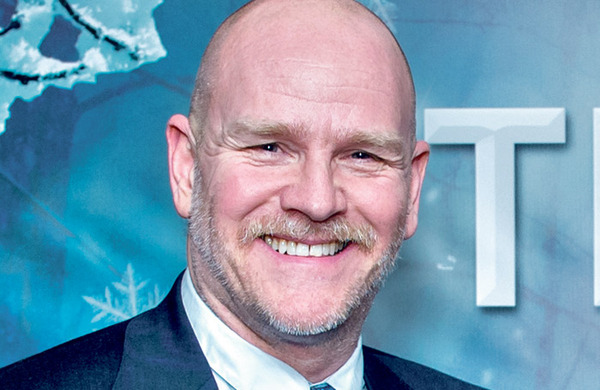

Frantic Assembly's Scott Graham: ‘We were the right company, in the right place, at the right time’

Influential British theatre company Frantic Assembly is celebrating its 25th year. Co-founder and artistic director Scott Graham tells Lyn Gardner about making work without co-founder Steven Hoggett, building a relationship with an audience, the importance of education and directing with Kathy Burke on new show I Think We Are Alone

About twice a week, when he’s in rehearsals, Scott Graham thinks about quitting. “It’s not easy making good work,” the co-founder and artistic director of Frantic Assembly says. “It’s hard. I often struggle and think: ‘Why am I putting myself through this?’ I find the process of making a show painful and full of doubt.” That’s despite the fact that Frantic Assembly, which is celebrating its 25th year, not only has a string of hits behind it but is also one of the most influential British companies of the last quarter of a century.

Companies such as Complicité, Forced Entertainment and Cheek by Jowl may have higher international profiles, but Frantic has been at the coalface of British theatre – showing a punky DIY spirit can pay dividends, and having the generosity to put education and the passing on of skills at the top of its agenda.

Frantic has made some of the most memorable shows of the past two decades, from Abi Morgan’s Tiny Dynamite in 2001 through the violently watchable Othello seven years later, which gutted Shakespeare’s play and relocated it to a run-down pub in a post-Industrial Northern English town, to Andrew Bovell’s warm and tender family drama, Things I Know to Be True in 2016. But it has also done something more: it has inspired thousands of kids, especially those doing GCSE drama and A-level theatre studies, to have a go.

Student drama is full of Frantic wannabes, and the company has almost single-handedly transformed the language of British theatre by showing that stories benefit when they are told physically and not just with words. If theatre is a much broader church than it was in 1994 when the company set off on its first tour – rather improbably with a production of John Osborne’s wordy Look Back in Anger – then Frantic has played a significant part in opening it up to a different vocabulary and different ways of working.

But despite all his experience, Graham still doesn’t find that making shows gets any easier. “It’s not about suffering for the sake of suffering, it’s about trying to explore and go places you’ve never been before, and that means digging deep,” he says. “I know that often means it is going to hurt.”

Going to the dark side

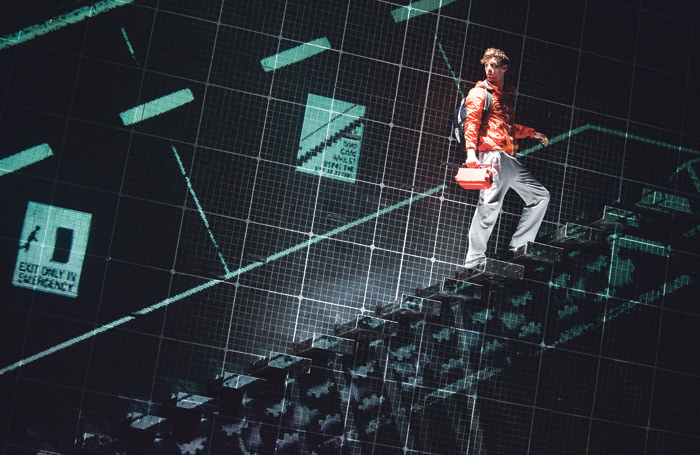

We meet at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre where he is rehearsing Frantic’s latest show, I Think We Are Alone, with co-director Kathy Burke. It’s a piece on loneliness and love by TV writer Sally Abbott.

“If, when I am making something, I start thinking: ‘This is good’, I’m now wise enough to know it should set alarm bells ringing. If I think it’s okay then I know I’m not challenging myself,” says Graham. “I’m really wary of Frantic Assembly becoming one of those companies that with every show just tick off all your expectations of what a Frantic show is going to be. So, I think that if it means making some weirder choices and going to some dark places, it’s worth it.” The next Frantic show after I Think We Are Alone is likely to be entirely without words.

This willingness to shake things up, try something different with every show and do it with varied collaborators – initially with I Think We Are Alone, Graham tried working with a poet to create the dramatic spine, a process that failed to bear fruit – may come from the fact that when Graham and Steven Hoggett founded the company they had absolutely no idea what they were doing. There would have been no Frantic Assembly if, while at Swansea University, the pair had not attended a workshop run by Welsh theatre legends Volcano Theatre, which inspired them to set up their own company.

Graham and Hoggett learned on the job, creating a series of shows that offered an antidote to most of the theatre they had seen and which they found dull. “I really had very little experience of theatre,” Graham says, “and my understanding of it was that it was something dusty, musty and dead. But then Volcano made me realise it could be something athletic and visceral and I started reading some plays, including Look Back in Anger, and I was surprised to discover there was real fire in it.

“It made me think that if there was fire in these texts then there must be something else going on that made most theatre seem dull, and that must be in the presentation. If theatre felt dead and yet these plays are on fire, then who was killing theatre and how could we reignite these plays?”

Frantic followed Look Back in Anger with the Generation Trilogy, three pieces of devised work – Flesh in 1995, Klub the following year and Zero in 1998 – inspired by their own lives, which really started to build the company a following. Much of that following was young and comprised people who didn’t think theatre was for them. Their devotion to Frantic Assembly was like that shown by music fans to a group. In those early days, Frantic was rock’n’roll.

“We got lucky. We were the right company, in the right place, at the right time,” the co-founder says. But there was more to Frantic’s success than luck. It felt fresh and different to see Graham, Hoggett and their young casts hurling themselves across the stage, in contrast to an awful lot of British theatre.

Continues…

Scott Graham on…

…The first day of rehearsals

Never trust that good feeling on day one of rehearsals. I don’t mean to be negative, but you always feel everything’s great on day one, but none of it will make it into the show.

…Physical theatre

When people talk about physical theatre, they tend to think it is all about choreography. But it’s all about stillness and precision.

…Audiences

Actors need to understand how clever audiences are. Audiences are really active. If there is tension between two people on stage and they want to kiss and they don’t kiss, the audience will leave that night talking about the kiss they never saw. The most important thing is often the thing that is withheld.

…Actors understanding their bodies

We are still not far from a time in theatre when producers thought if you were the movement director that meant getting the actors to kick their legs a bit. It is such a misunderstanding of what movement and physicality is. We are working with actors so they understand their bodies and how to use them. Audiences love it because they understand that in our daily lives we all take our understanding of our relationships from our physical relationships to each other.

…Drama schools

Drama schools are opening up. Performers today are much keener to embrace a concept of total theatre than the actors of 15 or 20 years ago. Steven and I were always adamant that whatever an actor’s size or shape they can tell a story physically.

…Frantic Assembly’s education work

I realised I couldn’t do every workshop Frantic runs. But I could train the people who can. It is important all our education work is directly linked to me, the things I make, the risks I take, the mistakes I make and the discoveries that come out of the rehearsal room.

It was certainly physically demanding. Once, after those early shows, I asked Graham and Hoggett how much longer they could go on performing and they admitted ruefully that sooner or later the “knees would give out”. Shortly after the turn of the century, they were directing rather than performing, although they still, occasionally, returned to the stage. One gem was Tiny Dynamite, in which the pair played boyhood friends with such tenderness that it still lingers in the memory.

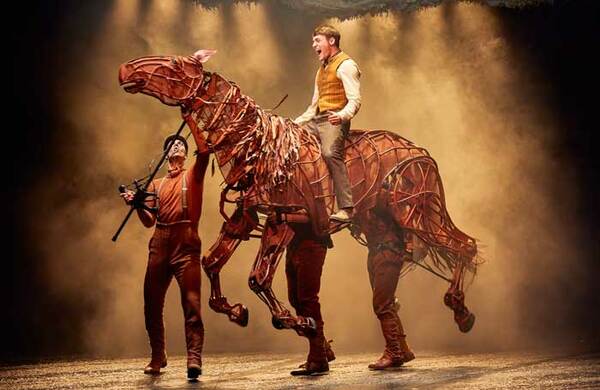

Both had freelance careers alongside Frantic – Graham is movement director on the upcoming Monsoon Wedding – but after increasing success beyond Frantic with shows such as Black Watch for the National Theatre of Scotland, on which he was the movement director in 2006, Hoggett gradually detached himself from the company.

The pair worked together on The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time at London’s National Theatre in 2012 and subsequently in the West End and on Broadway but in the next few years, Hoggett was increasingly to be found on Broadway’s red carpet leaving Graham as sole artistic director. Graham’s first solo show for Frantic was The Believers in 2014. When I interviewed Graham in 2015 he told me that because he had family commitments he had been unable to capitalise on freelance opportunities in the same way as Hoggett. As his family grows up, he may well be more open to offers if they come his way.

Something else that sets Frantic apart from its peers and ensured its success from the start was a willingness to open up its ever-evolving process to schools, colleges and other practitioners. It was as if in the act of teaching their process Graham and Hoggett started to refine and define it.

Building its own audience

Unlike many companies that conducted workshops around their productions, often exploring the content and themes of the shows, Frantic invited people to share in the process, which was a boon to those teaching college and school courses. It tapped into a hunger to know how professional companies went about making theatre, and it had the welcome side effect of helping the company build an audience.

“We found that sharing our process created an audience. I think that is fundamentally the other way around from the way most companies see their relationship with their audience. Most people expect an audience to buy a ticket and see a show and then maybe take it further by doing a workshop. We did it back to front and it created an audience for us.”

Sharing the Frantic process, and what the creatives discover in the rehearsal room, has always been at the heart of the company’s work, with Graham saying that “if by sharing what we do, we have demystified theatre and made other people feel that they can do it too, then we have done our job”.

For every show the company creates an extensive resource pack. Graham, who was always much closer to the education work of the company than Hoggett, set up the Ignition Project in 2008, which operates across the country and has trained and offered ways into theatre for thousands of young men aged between 16 and 20, often with no experience or indeed initial interest in theatre. Anna Jordan’s The Unreturning two years ago – a bruising look at the effects of war on the people who fight them – was cast entirely from graduates of the project and was a real validation of the company’s unsung commitment to education and training.

Continues…

Q&A Scott Graham

What was your first non-theatre job?

Saturday job in a sports shop. The coolest Saturday job in town. And then working summers in an electrical-component warehouse.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Artistic director of Frantic Assembly. Before that, I was an unpaid but very grateful performer in Volcano Theatre’s Manifesto.

What is your next job?

Movement director for Monsoon Wedding.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

It’s okay. Lots of people don’t know what they are doing. You don’t have to pretend you do.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

Theatre director and choreographer Liam Steel has been a huge inspiration. I love his tenacity and invention. He has taught me to look at any situation and ask if it can work better.

What’s your best advice for auditions?

Don’t hide behind things. We will see through them. Search for truth. Less is more.

If you hadn’t been the artistic director of Frantic Assembly, what would you have been?

I have a stunning lack of imagination about this. Probably a teacher with a disappointing football career in the lower semi-pro leagues well behind him.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

Before the first show I always tell the performers to listen to each other and hear the words for the first time. Look each other in the eye and know that they have each other’s backs. And enjoy it.

Graham thinks Ignition is the most important work the company does, particularly at a time when arts provision is being squeezed in schools. Frantic has piloted a female version, which it intends to launch this year, though the company is entirely dependent on finding funding and sponsorship to support it.

“For me, Ignition is important because it goes right back to the start of the company. We would never have set up Frantic if Volcano hadn’t recognised how excited Steven and I were by discovering what they were doing and thinking we might have something to offer. The lengths they went to encourage us made me realise that very little happens in theatre without that kind of encouragement. You need people who will take you seriously and help to open the doors.”

But while Graham and Frantic are deeply invested in supporting the next generation coming through, he is not sure that it would be possible to set up a company such as Frantic now. “At least not if you came from my background. Steven and I had nothing like the levels of debt people have now. It is really hard for those at the start of their careers now. It feels wrong to say that someone from my background would struggle to set up a Frantic Assembly today, but if it was me coming from the background I came from it would be really hard to justify taking the risks we took back then.”

Not that it’s necessarily getting any easier for a company to make work and get the rehearsal periods the work needs, even one of Frantic’s reputation and experience. I Think We Are Alone is being made on just three weeks’ rehearsal, which Graham admits is a real squeeze and contributes to the pressures he feels.

“You have to work so fast and I worry we will run out of time,” he says. “It is one of the new realities of co-producing, which is becoming the only way to get projects off the ground. There isn’t much money around, co-producers are squeezed and then that squeezes us. Then there is the pressure to make the dates work with all the co-producers. But at least we have the dates. Lots of companies are being squeezed out of the touring circuit. It is worrying.”

Supporting new writing

Frantic’s backing of new writing is often underestimated as well, both as a commissioner of plays but also in expanding the idea of what new writing is and how much it is a collaborative process. The roster of writers who have worked with Frantic is strong: Abi Morgan, Mark Ravenhill, Michael Wynne, Chris O’Connell, Anna Jordan, Bryony Lavery and Simon Stephens have all been part of creating Frantic shows, and it has had an impact on how those writers approach subsequent projects. Lavery, who has worked extensively with the company on projects including Stockholm in 2007 and Beautiful Burnout three years later, put it beautifully when she said that working with Frantic has made her aspire to write silence.

“We have never been able to have a relationship with writers in the way Paines Plough or the Royal Court do. We have never been in a position to commission ideas, we only ever commission for particular projects,” says Graham. “I think that sometimes people think that when Frantic commissions a writer I am there hovering over their shoulder all the time, but that’s not the case.

“Working with Frantic isn’t going to be right for every writer but for those who really want to be collaborators, it opens up a world of possibilities including the power of writing silence. Writing silence is something that playwrights are much more open to than they once were, and it comes with an understanding that in a Frantic Assembly show every single person in the room brings something to every moment. Every day we are negotiating how we work together, and that’s difficult but it also makes it alive.”

Graham says that real collaboration comes from people admitting they don’t necessarily have the answers and working together on finding them in the rehearsal room. “I see lots of young theatremakers who are scared of being seen not to know the answer. But there is nothing more exhilarating than putting your cards on the table and saying: ‘I don’t know,’ because it is the perfect invitation for your collaborators to step forward. If it’s a genuine collaboration it is in those moments that your collaborators don’t go: ‘If you don’t know I’m getting the hell out of here,’ instead they move into the space. So, I think saying: ‘I don’t know,’ is one of the best things you can do.”

As Graham heads back to rehearsal, I ask him what his younger self would say about where he is today. “I would have been in total awe of where Frantic Assembly and I are now. My younger self would pull me on the sleeve and say: ‘Stop doubting and stop worrying. You’ve done all right.’”

CV Scott Graham

Born: Glasgow, 1971

Training: English literature BA (hons) at Swansea University; workshops with Volcano Theatre

Landmark productions:

• Generation Trilogy, various tours (1995-98)

• Sell Out, Battersea Arts Centre (1998); Ambassadors Theatre, London (1999)

• Hymns, Lyric Hammersmith (1999)

• Tiny Dynamite, Lyric Hammersmith (2001)

• Dirty Wonderland, Grand Ocean Hotel, Brighton (2005)

• Pool (No Water), Lyric Hammersmith; Theatre Royal Plymouth (2006)

• Othello, Theatre Royal, Plymouth (2008); Lyric Hammersmith (2015)

• Things I Know to Be True, Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide; UK tour (2016)

• Fatherland, Manchester International Festival (2017)

Awards:

• TMA Award, best director for Othello

Agent: None

Tara Arts’ Jatinder Verma: ‘I don’t think the question of multiculturalism has been solved’

Opinion

Recommended for you

More about this venue

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99