My favourite play: Richard Eyre

Which productions most inspired, moved and delighted our leading theatremakers? Director Richard Eyre chooses a Shakespeare staging that confounded his expectations

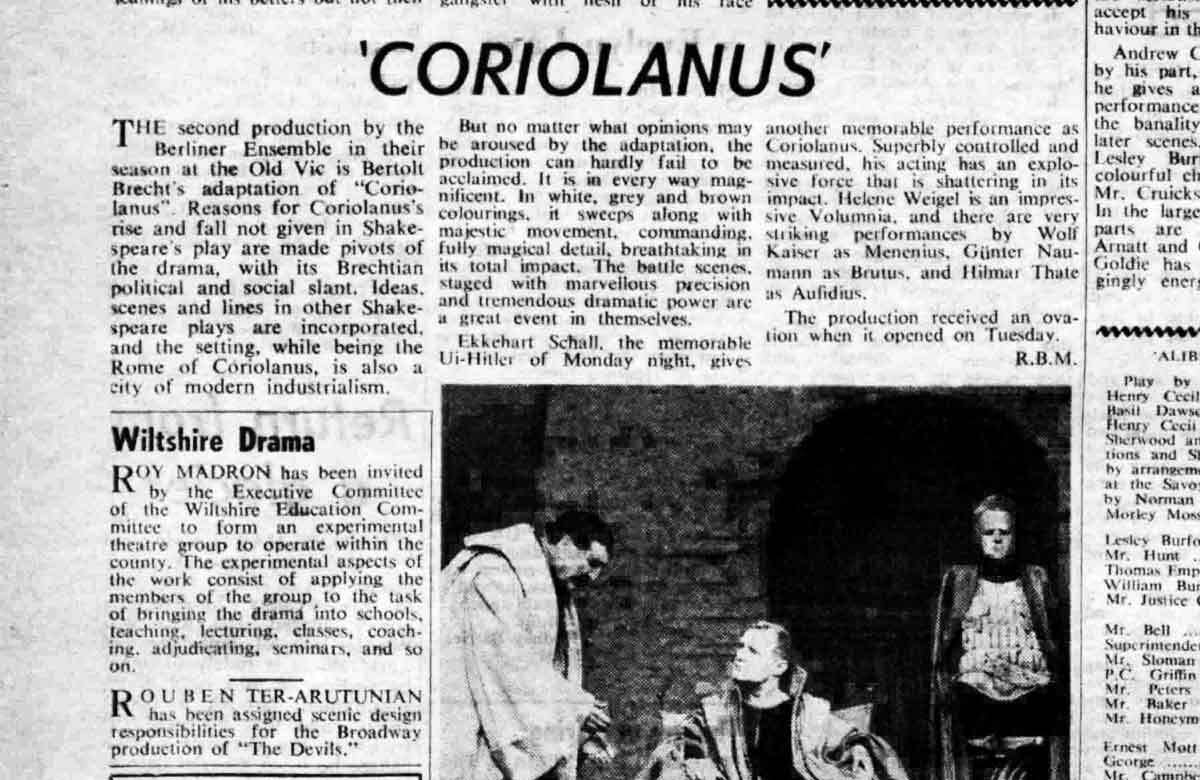

Coriolanus, the Berliner Ensemble at the Old Vic, London (1965)

I had been taken up by John Neville who ran Nottingham Playhouse. He came to see the first production I did at Leicester’s Phoenix theatre and then asked me to be an assistant. He was like a godfather and he took me to see the Berliner Ensemble.

This was before Brecht became widely produced here and I sense that back then, his plays were done not very often and not very well, probably in a slightly precious and pious dilution of what was imagined to be Berliner Ensemble style. But in August 1965, I saw the company do Brecht’s version of Coriolanus, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui and The Days of the Commune at London’s Old Vic.

I happened to have read Coriolanus, which was quite unusual for me at the time because I’d studied English at Cambridge. But everything about the productions confounded my expectations. I’d thought they’d be lucid and robust, but I wasn’t prepared for their visceral power, most of all Coriolanus. The design by Caspar Neher was simple but extraordinarily evocative, with not an atom of decoration about it. Not a scenic element was wasted – everything, including the performances, was expressive, minimal, distilled and exemplary.

Continues...

I don’t speak German, but I was extraordinarily moved by it, most of all by the wit and the bravura of Ekkehard Schall’s performance as Coriolanus. He was absolutely prodigiously brilliant, like a combination of Anthony Hopkins and Jonathan Pryce: very mercurial and charismatic.

But it was also the sheer astonishing beauty of Helene Weigel as Volumnia. The single most expressive gesture I’ve ever seen on a stage came at the end of the scene when Volumnia says goodbye to her son who is off to battle and she’s certain it’s the last time she will see him. As Schall turned to go, Weigel raised her right arm in a military gesture, initially like a Nazi salute, then, as he left the stage, it loosened with a faint, and infinitely touching, bending of the fingertips; the iron woman became a mother, grieving for the loss of her child.

John had been a great star at the Old Vic, so he took me around afterwards to meet Schall and Weigel. I was utterly star-struck, to the point that meeting Laurence Olivier a while later was a little bit of an anticlimax.

Analysis – David Benedict

Of Bertolt Brecht, critic-turned-dramaturg Kenneth Tynan wrote: “This stubby Marxist with his monkish tonsure and smelly cigar was a poet who believed that the exercise of reason could be made theatrically beautiful.”

To prove his point, in 1963, around the founding of the National Theatre at London’s Old Vic, Tynan took Olivier to Berlin where they stood at Brecht’s grave with his widow, Helene Weigel, and saw the company that Brecht had founded, the Berliner Ensemble, in two productions. In the canteen afterwards, Olivier remarked: “This isn’t just a theatre – it’s a way of life.”

This is how the Ensemble came to London, with those productions plus its newest, Coriolanus, which had been in preparation for literally years. Decades later, Antony Tatlow, drama professor at Trinity College Dublin, wrote: “It made the hopelessly conventional English Shakespearean productions appear vacuous, abstract and theatrical, merely rhetorical, dramatic fashion shows for superficial flourishings of language and lazy stylisations.”

Opinion

Recommended for you

Opinion

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99