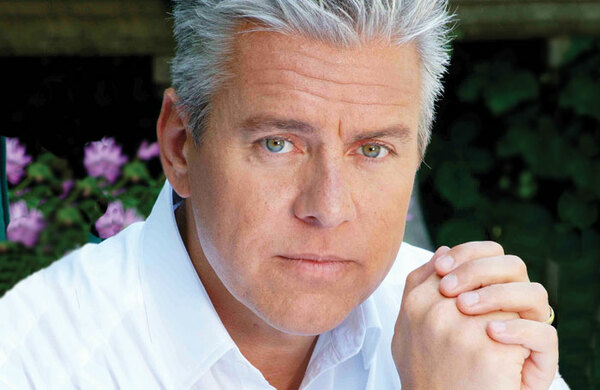

David Ian: ‘I had no prospects. I had nothing to lose, so I went for it’

THIS IS NOT A PAYWALL

Serious about theatre?

Join over 100,000 theatremakers who rely on The Stage for trusted news, reviews, and insight.

🔓 Sign in below or create a free account to read 5 free articles.

Want to support independent theatre journalism? Subscribe from just £7.99 and unlock:

🗞️ Unlimited access to award-winning theatre journalism

⭐ 1000+ reviews from across the UK

📧 Breaking news and daily newsletters

💡Insight and opinion from writers including Lyn Gardner & Amanda Parker

🎟️Discounts and early access to The Stage’s events

Opinion

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99