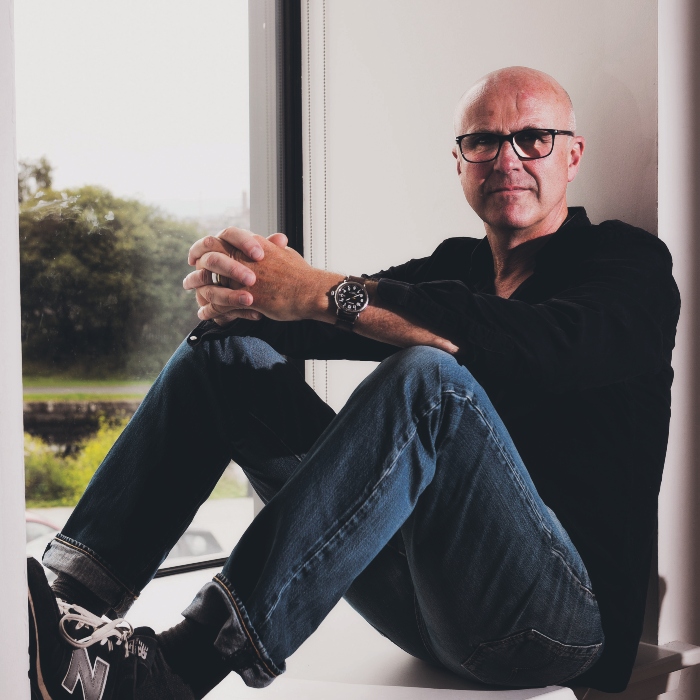

Tim Crouch

Tim Bano

Tim BanoTim Bano is an award-winning arts journalist who has also written for the Guardian and Time Out, and worked as a producer on BBC Radio 4. ...full bio

For nearly two decades, playwright Tim Crouch has brought experimental work to the nation’s biggest stages. As his latest convention-busting piece opens at the Edinburgh International Festival, he tells Tim Bano about locating theatre in the minds of the audience, learning to work with mainstream venues and branching out into TV

A mother travels to South America to find her daughter. That’s the plot of Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation, a new play premiering at the Edinburgh International Festival this summer. Simple enough.

Except the play is by Tim Crouch, destroyer of form, breaker of boundaries, the country’s pre-eminent experimental playwright. Which means there’s also audience involvement, and the end of the world, and a deep interrogation of the point of theatre in the first place.

Since his first play My Arm in 2002, Crouch has been pulling apart all the things that audiences take for granted in theatre. His work has been acclaimed and studied and dissected for almost two decades, and all the while has asked what it means to be an audience member, and what it means to experience a play.

Is ‘theatre’ the actors and the props on stage? Or is it the picture we each create in our minds when we watch? In previous pieces, Crouch has stretched the imaginative act of being in a theatre as far as he can. For most plays, the audience sits in the dark, pretending the people on stage are other people, imagining a bit of wood is a piece of furniture or a room or another world.

But in My Arm, about a boy who puts his arm in the air and keeps it there for 30 years – Crouch’s first collaboration with Andy Smith and Karl James, who have been co-directors of his work for almost 20 years – audience members became active participants of the show offering up things they had on them – a set of keys, a mobile phone – to play the characters.

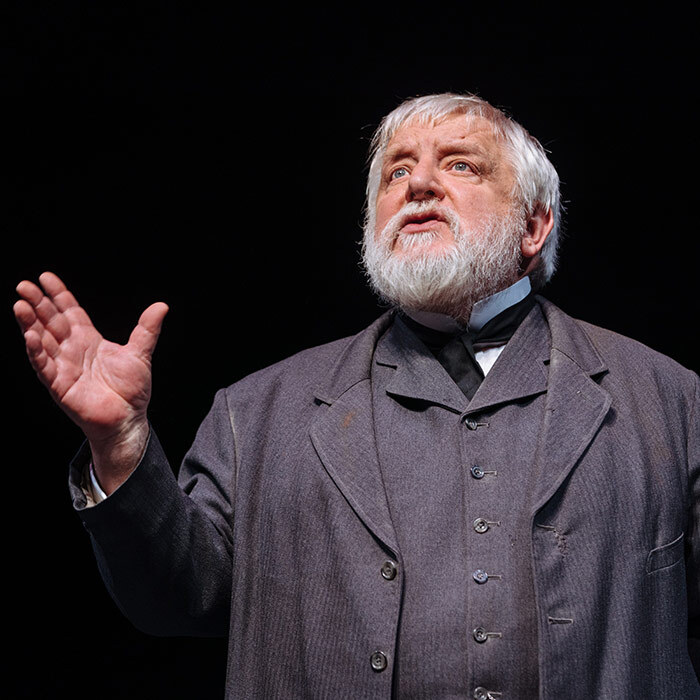

In An Oak Tree, which premiered at the Edinburgh Festival three years later, Crouch played a hypnotist while another actor played a father grieving the death of his child. The second actor was not allowed to have seen or read the play before. They read lines script in hand, they responded to prompts from Crouch. They could be male or female. Crouch describes the character as: “6ft 2in, your lips are cracked, your fingernails are dirty,” but the audience might be watching Frances McDormand or David Morrissey or Alanis Morissette (just three from the extensive and extraordinary list of people who have performed the play).

The Author, in 2009, was about a playwright called Tim Crouch who had written an extremely violent play. The audience faced each other in two banks of seats, and questioned the responsibility of being a spectator, of the gap between watching and taking action. There were lots of walkouts, both scripted and unscripted.

There’s a constant slippage between what the audience is seeing, and what it is told it’s seeing. For Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation, that interrogation continues. It’s another collaboration with Smith and James, who have co-directed five previous pieces by Crouch, and again it is formally inventive, putting the audience and its experience of theatre at the forefront.

The lights don’t go down. The audience sits in two concentric circles, each given an illustrated book from which they read the play. “This is another angle of approach to a perennial obsession of mine: where does theatre live?” Crouch says. “And a profound scepticism that it resides in the material stuff, and a profound hope that it resides inside the minds of an audience.

“The audience is invited to read. It will be crunchy at times, it will be difficult at times, and the invitation might not be taken up. We’re not forcing anyone to do anything. I don’t want an audience to feel they have to read well or nicely.” He jokes: “My nightmare audience in a way is a group of drama school students.”

But while the actors are revealing who they are, the audience has detailed visual representations to show them that it’s a lie. “There are three main characters in the play and they are drawn to look nothing like the actors who will perform them. My character looks a little bit like actor Zach Galifianakis. Illustrator Rachana Jadhav and I said: ‘Who doesn’t look like me? Zach Galifianakis.’ That’s the point of the whole thing: I don’t know what we trust the most. Do we trust the pictures? Do we trust the action?”

The play tells the story of a group of people who think the world is about to end. They have travelled to South America because they “believe in a set of ideas propounded by a man”. Crouch continues: “They have committed their lives to those ideas. Those followers can be perceived politically, religiously, spiritually but also theatrically.”

There is, of course, a political dimension to the idea of a man bringing together a group of people through ardently held beliefs, “whether that’s Trump in America or the things that are happening in this country or religion around the world”. Crouch draws on that because he sees a parallel in theatre: believing what we’re told by people on stage who know they’re lying to us. Where does a demagogue or cult leader end and a playwright begin?

As he points out, though, one of the most fundamental parts of the play is its story. There is in this new work, amid all the formal playfulness, a story about a mother and her daughter. That is also true of My Arm, An Oak Tree, Adler and Gibb, and Crouch’s other works – they are all excellent pieces of storytelling.

It feels almost as though Crouch does everything he can to break the spell of the spectators believing in the story, and yet it doesn’t break. Why do we still believe in the father grieving his child, or the boy with his arm in the air?

Playwrights are dictators – they submit the audience to the fiction of their manifesto

“Because I think – I hope – there is an honesty, the honesty of the storyteller who goes: ‘Hi everyone. My name is Joe. I’m gonna tell you a story.’ Playwrights are dictators. For the duration of their play they submit the audience to the fiction of their manifesto. You go to a piece of work and for that length of time you have to submit – and you often do it willingly. Sometimes if the play is shit you do it kicking and screaming. But if you are honest with the fiction then we can approach it from a considered perspective.”

Continues…

Q&A Tim Crouch

What was your first non-theatre job?

Bristol Fish Market, delivering fish around the South West.

What was your first professional theatre job?

We formed a theatre collective – Public Parts – at the end of my second year at university. That was my job for eight glorious years, on and off.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Nobody really knows.

Who or what was your biggest influence?

My dad.

What’s your best advice for auditions?

Bring your engagement with the world into the room, not your desperation for a job.

If you hadn’t been a writer and theatremaker, what would you have been?

I’m a child of two state school English teachers. That.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

No. But I avoid getting myself into dramatic situations where warm-ups are entirely necessary.

From outsider to the mainstream

Crouch began his career creating devised work with a company called Public Parts, touring small venues in the South West. He tweeted recently: “We were bloody-mindedly anti-London and stupidly self-absorbed. We thought we had the answer and everyone in London was an opportunistic, bourgeois sell-out. It was the best eight years.”

But as that work faded, and he struggled to find work as an actor, in his late 20s Crouch attended Central School of Speech and Drama. Through his 30s, he grew increasingly frustrated with the way theatre was working: its reliance on realism, its hierarchical structures, its obsession with money and its disregard for the involvement of the audience.

“Before I started to write, I used to bitch and moan about those things and thought I could either carry on bitching and moaning or I could make work that would demonstrate an alternative model.” So he wrote My Arm, his first play, an attempt to fall back in love with theatre.

In the years since, despite “glimmers of hope” like National Theatre Scotland, for whom Crouch is full of praise, many of the structures that he found frustrating have only become worse: “Theatres don’t run shows unless they have names attached to them. And that’s a really desperately difficult direction in which theatre is going because that is about money. So to be making work that is countercultural to that is kind of a hiding to nothing.”

And yet, Crouch is now seen as one of the most important writers and theatremakers in the UK. The Author was staged in the Royal Court upstairs space in 2009, the extraordinary Adler and Gibb in the larger downstairs space in 2014. An Oak Tree was put on in the NT’s Temporary Theatre in 2015. Those spaces would mark the high point of most writers’ careers. On top of that, he has become renowned for his plays for young people, and for directing – including The Taming of the Shrew at the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2011.

So what happens when the countercultural rebel becomes a part of the mainstream? “I don’t feel at all mainstream,” he says. “Certain major institutions still don’t reply to my emails.”

Crouch’s method is to sidestep the structures that usually dictate what work gets made or doesn’t “by just making work that is simple, light, dematerialised and can be done cheaply, and could be easily done by myself – a play that if no one wanted it, I would probably have made it anyway”.

But that’s not always possible. Even as an outsider, he still wants his plays to be staged. Short of buying a warehouse and funding it all himself – a tempting idea, but one for which he “lacks the resources” – that means having to be a part of the system that his work tries to escape.

If he can’t remove himself from the system, or destroy it completely, Crouch recognises that he has to learn to deal with it. “I’m excited about playing in the system. And if there is a dismantling of that system to be done, it must be done incrementally. You have to be canny and work within it to some degree and try to find your power in it.”

At the beginning of the year, Crouch and collaborators Smith and James wrote a document about how they work. It’s essentially an FAQ to send to organisations they’re working with. He was finding that organisations often have an “off-the-shelf mentality” to putting on a play, asking the artist and the writing to force themselves into the organisation’s fixed structure, “which is problematic because you should look at what the play is, what the writer’s trying to do and then alter your systems accordingly, rather than to place the artist or the company into a fixed structure”.

“We think theatre that’s created abusively is not good theatre,” the document says. “We think it’s important to pay attention to the quality of conversations with everyone who has a connection to the play – actors, producers, designers, casting, front of house, marketeers, publicists, cleaners, co-producers, ushers, audience, etc. For us, the production is not only made in the rehearsal room but throughout the organisation.”

It talks about timeframes – “We’re not keen on doing things last minute. We like to plan realistically and deliver the plans we make.” – and ends by saying: “We welcome the chance to listen and learn and most importantly to work together with you in a relaxed, creative and relatively stress-free way, mainly because it really helps the work and makes life a bit more enjoyable.”

Crouch says: “The document has come from years of having those conversations on an ad hoc basis. We didn’t force anyone to read it. I imagine that people didn’t bother to read it, which I’m totally okay with. But it’s important as a statement of how we like to work in a kind of non-hierarchical way as much as possible.”

It’s come about because, in the last 17 years, “I think we’ve been quite deferential to the organisations. Because they’re proper fucking theatres. And that is their life. That’s what they do all the time. And so to find the delicacy in tone that wouldn’t piss an organisation off, to say: ‘This is how we like to work’, took a long time.”

Branching out into television

Crouch’s approach to making theatre means his last piece of work is something of a surprise: a naturalistic dark television comedy called Don’t Forget the Driver, written with Toby Jones. It follows a put-upon coach driver, played by Jones, in Bognor Regis who finds an asylum seeker on his coach after a cross-Channel trip. When Crouch came up with the idea, he knew that it wouldn’t work for theatre, that the potential for crossover between the two mediums was extremely limited. “I’m not Phoebe Waller-Bridge.”

Nor has his TV foray fed back into his theatre work: “I wouldn’t put my theatre and this recent TV experience in the same solar system, let alone the same world. There was a technical, financial, logistical juggernaut of considerations. What is it TS Eliot said? ‘Between the idea and the reality falls the shadow.’ The shadow is an interesting one in television, but the shadow is heavy and it involves 60 people on set and script development and getting it in under 29 minutes and all that sort of stuff. So it was a new thing for me and I can’t easily extrapolate from that experience back into the theatre.”

It’s a completely different approach from writing for theatre, knowing that everything had to take place in a certain time frame at a certain pace, but Crouch and Jones did try to slow it down as much as possible: “There is a moment where a boat is winched up a piece of shingle and it was the happiest moment of my life because we managed to have it last for 25 seconds.” A second series hasn’t been confirmed – Crouch is still waiting to hear – but he would love it to happen.

For now, he’s focusing on Terrestrial Salvation, whose script went to the printers a few weeks ago. “Which is horrible because this week I realised that a line I had cut has found its way back into the performance text. And I can’t change it. That’s what we will rehearse with and perform with. So we are now working out how to make this the best thing it can be rather than thinking: ‘Should this line or that scene be cut?’ I can’t do any of that. It’s good.”

Besides, he finds there’s always something missing in every piece he creates. “If I were to write the perfect play then the world would end.”

CV Tim Crouch

Born: 1964, Bognor Regis

Training: Drama, University of Bristol (1985)

Landmark productions:

Theatre:

• My Arm, Traverse Theatre (2003)

• An Oak Tree, Traverse (2005)

• England, Edinburgh Festival Fringe (2007)

• The Author, Royal Court, London (2009)

• I, Malvolio, Brighton Festival, (2010)

• What Happens to the Hope at the End of the Evening, Almeida (2013)

• Adler and Gibb, Royal Court, London (2014)

• The Complete Deaths, Spymonkey (2016)

• Beginners, Unicorn Theatre, London (2018)

• Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation, Edinburgh International Festival, National Theatre Scotland and Royal Court (2019)

TV:

• Don’t Forget the Driver, BBC2 (2019)

Awards:

• Prix Italia award for best adaptation in radio drama for My Arm (2004)

• Herald Angel (2005) and Obie Awards special citation (2007) for An Oak Tree

• Fringe First, Total Theatre and Herald Archangel awards for England (2007)

• Brian Way Award for children’s playwriting for Shopping for Shoes (2007)

• John Whiting and Total Theatre awards for The Author (2010)

• Writers’ Guild of Great Britain award for best play for young audiences for Beginners (2019)

Agent: Giles Smart, United Agents

Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation runs at the Studio, Edinburgh, from August 7 to 25. Details: eif.co.uk/whats-on/2019/totalimmediate

More about this organisation

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99