Fergus Morgan

Fergus MorganFergus Morgan is The Stage’s Scotland Correspondent. He has also written for The Scotsman, The Independent, TimeOut, WhatsOnStage, E ...full bio

He wanted to be a dentist and saw acting as something to do on the side, but after flunking his exams Luke Thallon decided to apply to drama school. A decade later, after working with many of theatre’s leading names, he’s diving into his Shakespeare debut at the very deepest of ends – by playing Hamlet at the RSC. He talks to Fergus Morgan

Paul Scofield, David Warner, Alan Howard, Ben Kingsley, Michael Pennington, Mark Rylance, Kenneth Branagh, Toby Stephens, Alex Jennings, David Tennant, Jonathan Slinger, Paapa Essiedu. The list of actors who have played Hamlet with the Royal Shakespeare Company is an illustrious one. This month, Luke Thallon will become the newest member of that club. Remarkably, it is not only the 28-year-old actor’s first time working with the RSC. It is also his first professional Shakespeare.

“I know, the hubris,” Thallon laughs over video from his digs in Stratford-upon-Avon. “I have talked about doing other Shakespeares. It looked like one was going to happen before Covid. I did think, because I’ve known I would be doing this for about two years, that I should do another one before we started, just so I understand what it takes.”

I put it to Thallon that, sensible though that might have been, it does spoil the fairytale of his first professional Shakespeare being perhaps the biggest role in all of theatre.

“Yeah, it is more fun like this, I guess,” Thallon agrees. “And there is something about the character of Hamlet being a quiet, intellectual sort of outsider in his world, so maybe it suits the play. I might be the only person in the company who has not done a Shakespeare before, which is stupid and crazy and silly, but it sort of works.”

Did the fact that he had not done any professional Shakespeare make Thallon pause when he was offered Hamlet? What was his first thought when he accepted the role?

“My first thought was: ‘Oh, God, oh no, if you get this wrong, there’s no hiding from it.’ ” Thallon says. “It is a big stamp on your forehead if it isn’t very good. Obviously, the word ‘Hamlet’ is very exciting, but then comes the reality of: ‘Oh, shit, now I have to do it.’ ”

‘I run five miles a day and I don’t drink, but we’ve run Hamlet twice now and there’s a point in Act V when I’ve got nothing left’

After that, continues Thallon, came a flood of questions about the famous tragedy.

“What is it about, and what does it mean?” he asks. “What is this big sprawling, complicated play that is so many different things at once? It’s a political thriller. It’s a family tragedy. It’s a meditation on existentialism. It’s a play within a play. One feels, if it was written today, a dramaturg would pull Shakespeare aside and say: ‘Look, Bill, you need to pick a lane here.’ ”

Continues...

Born in 1996, Thallon grew up in Woking. His parents were both professional volleyball players, and it was obsessively watching a Cirque du Soleil DVD lent to them by a friend that first sparked Thallon’s love for performance.

“It was this four-DVD set that I watched religiously when I was really young,” Thallon remembers. “I was struck by the whole theatrical experience. At school, though, I did a lot of sciences to go and become a dentist. Drama was always something on the side.

“Then, I was off at a National Youth Theatre course one summer, and my mum told me that I’d failed my science AS levels,” Thallon continues. “I thought: ‘Well, bugger, I don’t think dentistry is going to be the thing for me.’ So, I applied for drama schools instead.”

Thallon graduated from Guildhall in 2017. It was while he was training in London in the mid-2010s that his theatrical education really took place. We chat enthusiastically about several shows, including Carrie Cracknell’s staging of The Deep Blue Sea at the National Theatre and Robert Icke’s version of Uncle Vanya at London’s Almeida Theatre, both in 2016.

“The performances I keep close to my heart are Paul Rhys in Uncle Vanya and Helen McCrory in The Deep Blue Sea,” Thallon says. “I keep them in an imaginary pendant around my neck. Oh, and Stephen Dillane in Faith Healer at the Donmar Warehouse [also in 2016].

“Isn’t it amazing that shows like that can happen?” he adds. “Shows like that come along and bite chunks out of all of us and then disappear, but we are still talking about them today. I love this about theatre. It infuriates me and confuses me, but I love it.

“And the best thing of all is that neither Uncle Vanya nor The Deep Blue Sea got showered with awards or transferred to the West End,” Thallon continues. “The critical reception was, like, three and four stars, yet we are still talking about them now. That’s all you need to know about that side of things, really.”

Decluttering texts

Anyone who has seen Thallon on stage will understand why it makes sense to cast him as Hamlet, despite his lack of Shakespearean experience. He stood out from his first professional role, a small part in Mike Bartlett’s Albion at the Almeida in 2017, through his gangly gracefulness and angsty, halting delivery. He then continued to earn praise for his performances in a remarkable string of critical hits: Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance at the Young Vic in 2018, Noël Coward’s Present Laughter at London’s Old Vic in 2019, Tom Stoppard’s Leopoldstadt in the West End in 2020, Peter Morgan’s Patriots at the Almeida in 2022 – then in the West End in 2023 and on Broadway in 2024 – and Conor McPherson and Elvis Costello’s Cold War at the Almeida in 2023-24. In 2022, The Stage named him among a list of 25 theatremakers of the future.

Continues...

Thallon has a compelling presence on stage. His characters – from an awkward teenager in Albion to billionaire Roman Abramovich in Patriots – always seem raw and real. He delivers lines as if the words are occurring to him right there and then. The prospect of him finding fresh meaning in Hamlet’s seven soliloquies is a thrilling one.

“My focus on stage is always to be as honest as I can be,” Thallon says. “I try to declutter. I declutter, declutter, declutter until it’s just me, experimenting with how honest I can be in a particular moment. Perhaps that means lines come out as conversational. It’s not a trick, though. I don’t want it to appear casual. I just have no interest in doing anything that doesn’t feel totally honest.”

This approach has served Thallon well in modern plays. But how has he wrestled with the rhythms and rhymes in Shakespeare? It is, he says, a balance between respecting the poetry of the language and not being governed entirely by it.

‘I really do not want to be at a Shakespeare where I can hear the rhythm and see the line endings. I just can’t listen to it’

“Shakespeare is poetry,” Thallon says. “People say it is not poetry, but that is bullshit, just like when people say they are treating Hamlet like it is a new play, that is also bullshit. I get what they mean, but it is just not true. It is poetry. There are rhyming couplets. There’s a rhythm. It is not everyday speech. When people perform it entirely casually, I sit and think: ‘Why are you talking like this? This is not how people chat.’

“At the same time, though, I really do not want to be at a Shakespeare where I can hear the rhythm and see the line endings,” Thallon adds. “I just can’t listen to it. I actually can’t even understand what is being said. All I hear is dum-de-dum-de-dum-de-dum-de-dum. I think you can tell within seconds when someone has worked at a text from a place of rules and rhythm. The really hard thing to do is find that middle ground.”

There are some audiences – particularly in Stratford-upon-Avon – that might consider Thallon’s approach to Shakespeare heretical. For him, however, it is all about honesty.

“I don’t think it is heresy, to be honest,” Thallon says. “I am actually only echoing the sentiment that I was brought up to believe, which is that nothing fucking matters as long as it is honest. Why bother with rules if they are pulling you away from honesty? Why bother with rules if they are stopping you from finding meaning? If you have decided exactly how to say the lines beforehand, how can it possible be alive and present?”

Help from old hands

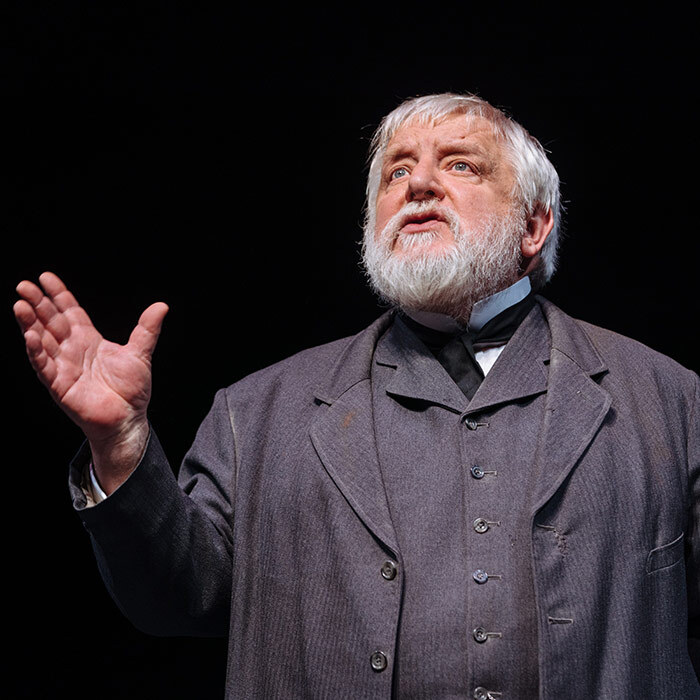

Thallon might be diving in at the deep end with Shakespeare, but he is at least surrounded by some old hands: Jared Harris as Claudius, Nancy Carroll as Gertrude, Elliot Levey as Polonius and Anton Lesser as the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Combined, this impressive ensemble has racked up dozens of Shakespearean credits.

“Walking to that first read-through, having never done a Shakespeare, and aware of Nancy and Elliot and Jared and Anton’s history, I really did think: ‘What the fuck am I doing?’ ” Thallon says. “It’s like going to play first violin in an orchestra having never picked up the instrument, in front of people who have been playing their entire lives.

“But they are the kindest, most generous, most open artists I could imagine being with,” he adds. “It is very intimidating and really scary but, my God, they really have become family. I feel like I can trust them all completely. They bring such profound lightness and seriousness in equal measure to every moment in the rehearsal room. I feel spoiled.”

Continues...

Thallon also has a familiar face directing him in Rupert Goold, the outgoing artistic director of the Almeida, who will take over from Matthew Warchus at London’s Old Vic next year. Goold directed Thallon in Albion, Patriots and Cold War.

“I first met Rupert for Albion,” Thallon says. “I was still at drama school and I had this really crazy week of auditions during our final show. I think I had eight or nine in a week and I was exhausted. Our meeting was very, very quick. It must have been under 10 minutes. I did the reading, got the part and did the play.

“We didn’t do another show for a few years, but we have done a lot of work together off stage,” he adds. “Readings of new plays, workshops for things that have never seen the light of day, things like that. Here is a crazy titbit, which I think I can say now, but I actually did all the workshops as Gareth Southgate in James Graham’s Dear England, which Rupert directed, even though I know nothing, like nothing, about football.

“We have a good relationship,” Thallon continues. “I definitely trust him and I hope he trusts me. I think he is really smart. Really smart. I think Rupert’s great gift is that he can watch something and simultaneously be looking at both the big picture – the blocking and the sound and the choreography – and at the tiny, microscopic subtextual details.”

‘Hamlet is such a contradictory animal. For every clue you find in the text about him, you find a different clue somewhere else’

How will Goold apply his skill set to Hamlet? What will his production look like? Previous productions have transplanted the play into different eras and locales. Last time around at the RSC, with Essiedu in the title role, Simon Godwin imagined Elsinore as the multicoloured capital of a fictional African dictatorship. Does Goold do something similar? The press release does not give much away, and nor does Thallon.

“I can’t tell you, sorry,” Thallon laughs. “I don’t want to say anything, other than that Rupert’s approach to Shakespeare, and he has said this publicly so I don’t think he will tell me off, is very particular and precise. He has a specific way in. The setting of the production is very specific and bold. It opens us up to some punny review titles.”

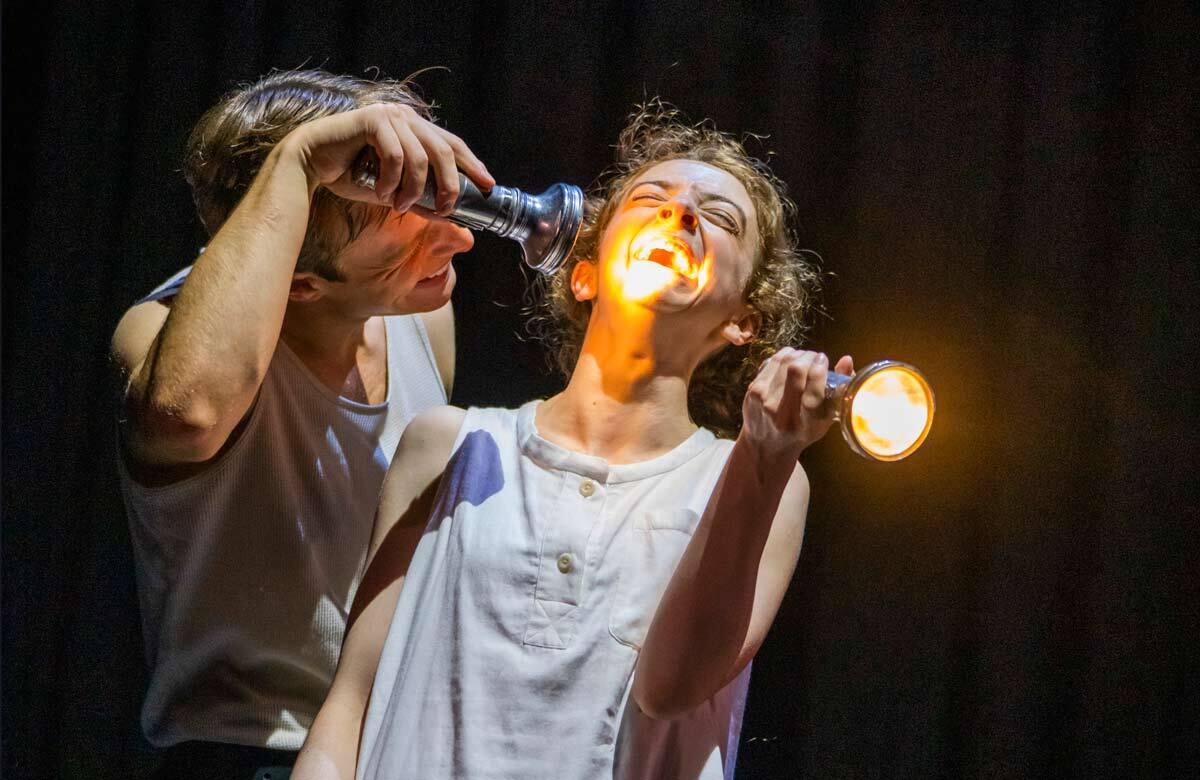

Thallon does drop a few hints. Goold’s staging is “extremely physical”, he says. The company includes dancers and the requirements on him are “literally acrobatic”.

“I’m quite fit,” Thallon says. “I run five miles a day and I don’t drink, but we’ve run the show twice now and there’s a point in Act V when I’ve got nothing left. It is the fight scene. We’ve fought a bit then we’ve been pulled apart. I’m downstage looking up at the rest of the company and I can feel that I’ve got nothing left in me. I need to get fitter.”

Continues...

Q&A Luke Thallon

What was your first non-theatre job?

I washed pots in a pub when I was 15.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Albion at the Almeida.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

There is no destination. You have to find fulfilment in the pursuit of fulfilment.

What’s your best advice for auditions?

I am terrible at them. I am the last person anyone should take advice from.

Thallon’s Prince of Denmark is athletic, then. What else can he say about his Hamlet?

“It’s interesting,” Thallon says. “Hamlet is such a wild, contradictory animal. For every clue you find in the text about him, you find a different clue somewhere else that completely contradicts that. You run out of options to think that you are playing a character. Pretty early on, you resign yourself to thinking: ‘Well, it’s just me.’

“You have to find yourself in it,” he continues. “Trying to find a character would be to reduce the play. Hamlet is not a character. He is a human being, full of contradictions.”

It sounds, I say, as if Thallon’s preparation to play the Dane has been all-consuming. He is even sporting a black turtleneck while we chat. Has he got a skull to hand, too?

“Oh no, how insufferable,” Thallon says. “You can’t put that in. This is honestly just the first thing I happened to grab from my wardrobe when I went out to get some coffee.

“But yes, it has been massively all-consuming,” he continues. “And scary because you see parts of yourself that are ugly. You see the world from different angles. I don’t think I’m particularly pleasant to be around at the moment. I’m pretty spiky and anxious.”

Thallon has already spoken about his admiration for the performances of McCrory, Rhys and Dillane in The Deep Blue Sea, Uncle Vanya and Faith Healer back in 2016. He also tells me about sharing the stage with two of the most celebrated performances of recent years: Andrew Scott’s flamboyant Garry Essendine in Present Laughter and Tom Hollander’s sinister Boris Berezovsky in Patriots.

“Present Laughter really was fun,” Thallon says. “Being on stage with Andrew was like stepping into the ring with a championship player every night. The main thing I remember about it, though, is that the after-show parties were constant. I don’t think I was ever in bed before 5am. That show was going to live on, but it didn’t because of Covid or Andrew’s schedule or something. I would still go back and do it again.

“Tom is an amazing actor, too,” Thallon continues. “I’d seen him in Travesties and adored it. That’s why I wanted to do Patriots, to work with him. I think Tom has possibly the greatest and most effortless command of an audience I have ever seen. He can silence a theatre with just a charming flick of the wrist. My God, he is good.”

The most influential Hamlet?

What about Hamlets? Who has Thallon seen take on the role he is about to inhabit?

“I saw Rory Kinnear’s when it came to Woking on tour when I was young,” he says. “I remember that I got a free ticket and sat at the back of the circle. I saw Michelle Terry do it at the Globe. I saw Andrew’s, which Rob Icke directed. And I’ve seen Lars Eidinger do it in Germany. I think the most influential for me was Lars’ at the Schaubühne in Berlin.”

And has he approached any ex-Hamlets for advice? Has he, perhaps, received the famous little red book, the mythical copy of the play that has been passed down generations of Hamlets, from Michael Redgrave to Peter O’Toole, to Derek Jacobi, to Kenneth Branagh, to Tom Hiddleston? Has Hiddleston handed it on to Thallon?

“I haven’t got the book, no, but I have spoken to a few people,” Thallon says. “I’ve actually spoken to Mark Rylance about it a lot. We went out for a very long, boozy dinner in New York and talked about it. He answered all my questions, but he kept saying: ‘Look, none of this will be useful, because ultimately, Hamlet is just you. You will form your own connection to it. The play stares into you just as much you stare into it.’”

Hamlet is running at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until March 29

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99