James Graham

The award-winning playwright, whose string of hits include Dear England, Ink and new productions Punch and Boys from the Blackstuff, talks to Andrzej Lukowski about how history informs his work and why he now likes to write stories about the kind of people he grew up with

“I think the general election will be either October 31 or November 14,” says James Graham, the day before Rishi Sunak calls the election for July 4. Yes, he’s the nation’s foremost political playwright. But he’s a geek, not a guru, and I think being so totally off the mark – his calculations were based on when the US election takes place – would tickle him.

We’re sat in a cafe at the National Theatre, the venue where his 2012 play This House gave him his first real hit after his 20s were spent jobbing away on the London fringe (notably the Finborough, where five of his early plays premiered). An almost indecently entertaining drama about the Labour whipping operations of the 1970s, This House heralded the arrival of Graham’s most recognisable form: a writer capable of taking real, often dry, historical events and synthesising vast numbers of voices and facts together into something lively and gripping and often hugely illuminating of forgotten corners of recent history.

It heralded an astonishing run of success with a series of dramas whose subjects range from the Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? ‘coughing major’ trial (Quiz) to a musical with songs by Elton John about the rise of televangelism in 1980s America (Tammy Faye) to last year’s smash drama about the renaissance of the England men’s football team under Gareth Southgate (Dear England).

‘What excites me is the stuff that’s adjacent to the main story’

Indeed, Graham’s net has spread so wide that if pretty much anything of note at all happens in the UK, there are people tagging him on social media to suggest he write a play about it – something I would have thought is intensely irritating, but in fact he is quite tickled by.

“It’s really efficient!” he laughs. “I get delivered stories that I may have missed.”

“The thing is,” he says, more earnestly, “when Liz Truss fell, for instance, you do get people saying: ‘Do you want to do a Liz Truss play?’ or ‘Do you want to do a Liz Truss movie?’ And what I’ve realised through that is no, I absolutely don’t want to do a Liz Truss movie because, actually, I’m not sure there’s anything left to find out about her. What excites me is the stuff that’s adjacent to the main story.”

Continues...

Expect the unexpected

There’s always something slightly unexpected about his projects. Even when dealing with figures such as Rupert Murdoch in his hit play Ink, he has an unusual angle. Since becoming successful, he’s not written in a serious way about any world leader, but he has written about Chris Tarrant and Southgate. (He does have a John Major play on the back burner – the most James Graham-ish PM possible).

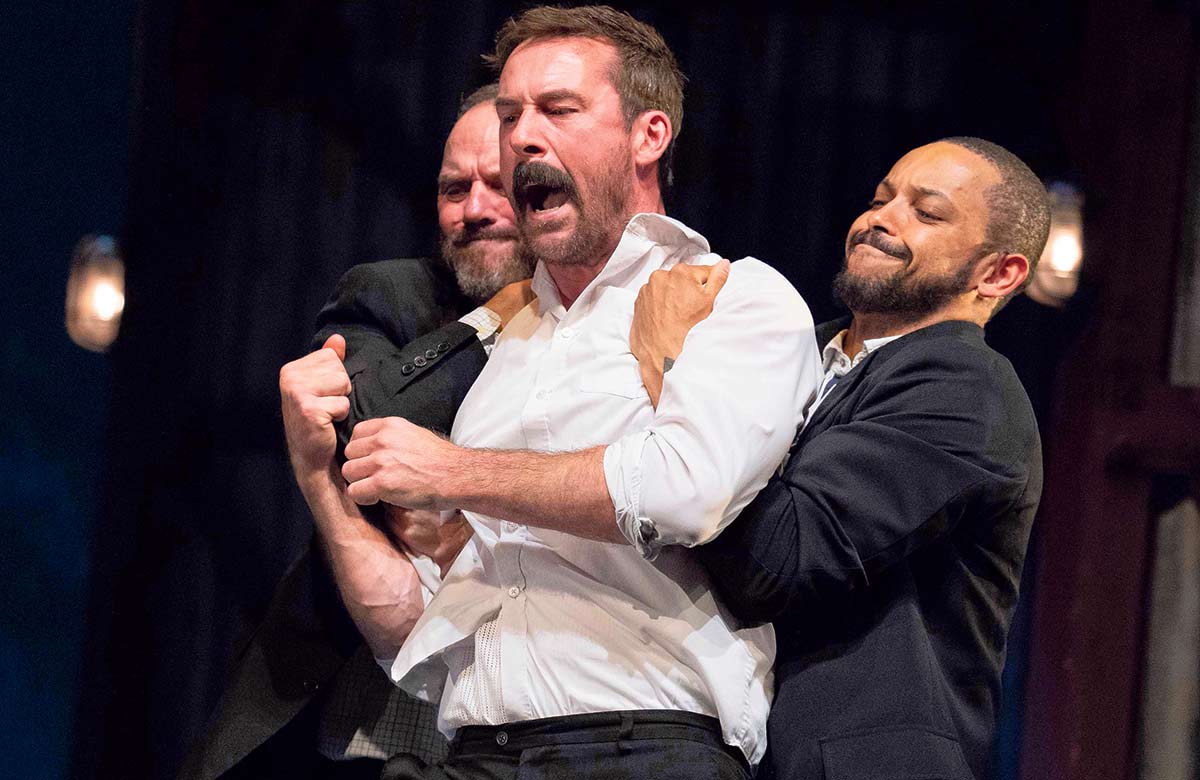

When we met at the NT in late May, he had two productions running in England: up in his native East Midlands there was Punch at Nottingham Playhouse. And there’s Boys from the Blackstuff, which played a short run in the Olivier and has now moved to the Garrick Theatre, where it runs until August. A transfer from Liverpool’s Royal Court, it’s Graham’s stage adaptation of Alan Bleasdale’s landmark TV drama about a group of laid-off labourers in early 1980s Liverpool at the zenith of the Thatcher-era recession.

As Graham tells it, Boys from the Blackstuff came about because the show’s director Kate Wasserberg – who had directed his Finborough play Little Madam back in 2007 – twisted his arm.

“She called me at quite a busy time, saying: ‘I’ve got a project for you.’ And I was absolutely determined that no matter what she offered me, I wouldn’t be able to do it. And unfortunately, the words ‘Boys from the Blackstuff’ came out of her mouth.”

A huge fan of Bleasdale’s work, Graham had watched numerous archive interviews with him on YouTube but was awed and thrilled by the fact that the proposed commission was conditional on the approval of the legendary screenwriter.

“We went up to meet Alan in Liverpool,” recalls Graham, “and had a meal with him in his favourite Chinese restaurant by the Mersey. I was really nervous, but people said: ‘Oh, he’s really cuddly and lovely’, and he’d read some of my work and thought maybe we could be a good fit. So he sort of set me off just as a test to see, to start writing some pages.”

‘I wanted to dramatise history, and I accidentally became a bit of a political nerd’

A follow-on from Bleasdale’s 1980 Play for Today, The Black Stuff – in which we see ‘the boys’ get laid off – Boys from the Blackstuff is an anthology about their lives on the dole. It really connected with the zeitgeist during the bleakest years of Thatcher’s first term, and is most enduringly famous for the character of Yosser Hughes, whose desperation has culminated in a mental breakdown, aggressively barking “gizza job” at pretty much anyone he meets (famously, he was played by the late Bernard Hill; Graham tells me Hill saw it at the Royal Court before he died).

It is not a project for Graham to put his stamp on: most of the dialogue is Bleasdale’s. However, Graham is a master at weaving a multitude of disparate strands into a single narrative, and that’s precisely what he’s done here, melding the five different standalone episodes – plus bits of The Black Stuff – into something that comes very close to a single narrative.

“You need a unity of story,” he explains. “So the first mental exercise I did was how to get them all in each other’s story: a bit like an Avengers crossover movie, looking for all their opportunities to mix. I know in our head we probably think of it as sort of really gritty social realism, of people being sad in kitchens. But there was a scale to it: Alan Bleasdale was basically the Scouse Arthur Miller. There’s an epicness to that work, with Liverpool as a background character.”

It’s not been modernised significantly, and is effectively a period drama. Which is fine, says Graham. “I think it has its own value. This happened to these people at this time and it was really cruel. But obviously it has resonance given the cost-of-living crisis. Then they couldn’t find work, and now we have so much work you need four fucking jobs.”

Continues...

Staging the real story

Graham is a proud East Midlander (he’s from Ashfield), and Punch is his first work for Nottingham Playhouse.

A dramatisation of true events, it concerns Jacob Dunne, a young man who killed trainee paramedic James Hodgkinson with a single punch in a senseless Nottingham bar fight, and what happened when Hodgkinson’s parents decided to try to help him turn his life around.

“Adam [Penford] the director approached me,” he says. “It was another of those things where I didn’t know whether I’d have time, but a Nottingham story meant so much to me that I wanted to start exploring it. And I guess I was thinking about blokes and masculinity a lot. And so it was like a Venn diagram of Nottingham, men, politics, the justice system… I couldn’t say no.”

It wouldn’t be unreasonable to call Graham Britain’s most successful working playwright: since 2017, he has had seven plays in the West End, all the more extraordinary when you consider that in the same time he’s had three hit TV projects (Sherwood, The Way and the TV adaptation of Quiz) and Tammy Faye, which premiered at the Almeida but is now heading for Broadway.

Clearly, he doesn’t need to work as much as he does. He seems fairly clear that he takes on too much work. But as a writer from a working-class background who has been a vocal advocate for the arts in recent years, I get the impression that he feels a certain amount of responsibility comes with his success. For all his talk of having his arm twisted to write plays for theatres in Liverpool and Nottingham, he has actually done it.

When I first try to engage him on the subject of how enormously successful he is, he looks as if he’d like the ground to swallow him. I rephrase and say he’s clearly going through a popular spell that gives him more clout than he used to have.

“You see a window of opportunity, yes,” he concedes. “There was a great pleasure in bringing all the national critics up to Nottingham to see Punch and seeing them seated alongside the East Midlands mayor and the local Nottingham MP.

I do feel a sort of civic sense of re-engaging what local theatre can be with Blackstuff and Punch.

“I spent the first 10 years of my career telling stories about people quite removed from my experience,” he continues, “politicians or editors of the Sun newspaper. Now I do like to write about people like the people I grew up with.”

He’s an eminently unassuming chap, and his interest in politics has absolutely nothing to do with his family or upbringing: “I would have loved to have said I was reading Hansard at the age of six or something, but no,” he laughs.

In fact, history was his real entry into the field: “I really loved history lessons and learning about politics through that is what got me into it. I wanted to dramatise history, and I accidentally became a bit of a political nerd.”

As his works are popular, they tend to raise awareness of their subjects. Punch, for instance, has been cited in both Parliament and by a judge sentencing a similar case. Nobody has done more to spread awareness of the 1970s Labour whipping operation than Graham. And there are those who have accused him of inadvertently engineering the rise of Dominic Cummings by writing a TV drama (Brexit: The Uncivil War) in which Benedict Cumberbatch starred as the volatile political strategist.

He sighs: “I totally accept that if Doctor Strange or Sherlock Holmes plays you then by default people will project some sort of superhero qualities on you. And we got people really mad because they thought we were suggesting he was this genius.

“But the problem with Dominic Cummings is, he actually is very clever and very talented,” continues Graham. “Where those talents should go is up for debate: probably not in the heart of our public life. But it felt important that the nation did know about him.

“What I think shocked me a bit was the arrival of the culture wars and quite a lot of people, even journalists – journalists on the left actually – going: ‘This is too soon, why are you doing this?’ And in the first 10 years of my writing life, no one ever said: ‘Why are you doing this?’ ”

Continues...

Writing about recent history can be a controversial business, but it has pretty much worked out for Graham. His Southgate opus Dear England is so up to date that it’s technically not even finished: shortly after our interview it’s announced that it will return to the National in 2025, complete with a new ending based upon this summer’s Euros.

It gave Graham his first Olivier for best play earlier this year: I wonder if Dear England’s victory felt special – his own 1966 if you will – or if he simply has too much work on to be overly invested in the silverware bestowed on a single play.

“It was really lovely,” he says. “I’m not going to say I don’t care. But I think people thought I’d won it before. Actually, I’ve been losing best play for nearly a decade now. I lost This House, I lost Ink, I lost Best of Enemies and they were probably more like that play that traditionally wins it.”

Now in his early 40s, it’s truly hard to imagine Pinter or Stoppard or Hare or whoever having such a sunny, approachable attitude at this stage in their careers. It’s also simply a fact that success slows most playwrights down, be that because their lives have become more comfortable or because they’ve been lured away by screen work.

Graham just really, really loves writing plays. And long may that continue.

“It’s great if I can squeeze a TV drama in around a play,” he says.

“But I never want to be squeezing a play in around TV drama. I feel like a part of the theatre community – I want to keep working and doing plays for the rest of my life.”

Q&A James Graham

What was your first non-theatre job?

Window cleaner. My stepdad had the round in our local village.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Stage-door keeper at the Nottingham Theatre Royal. For just over a year. Sometimes very long,16-hour days.

What is your next job?

As a writer? Adapting Dear England for the BBC. Or if you mean once people stop letting me write? Might give prime minister a go. For a rest.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

Loads of things. Don’t lose your accent at university to fit in. Don’t panic, take your time. Try to enjoy the journey even when it’s hard because it all travels by so fast…

Who or what is your biggest influence?

*gestures around* The real world.

What is your best advice for auditions?

Listen to the director’s note after the first reading, and make a strong offer for a shift, even if it’s the wrong one. And if it’s a new play, having some thoughts ready on what you read is no bad thing.

If you hadn’t been a playwright, what would you have been?

A teacher or Houses of Parliament tour guide.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

Whisky before the first preview. Or any preview, to be honest. Or… any show. Whisky, basically.

Boys from the Blackstuff runs at London’s Garrick Theatre until August 3. For more details click here

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99