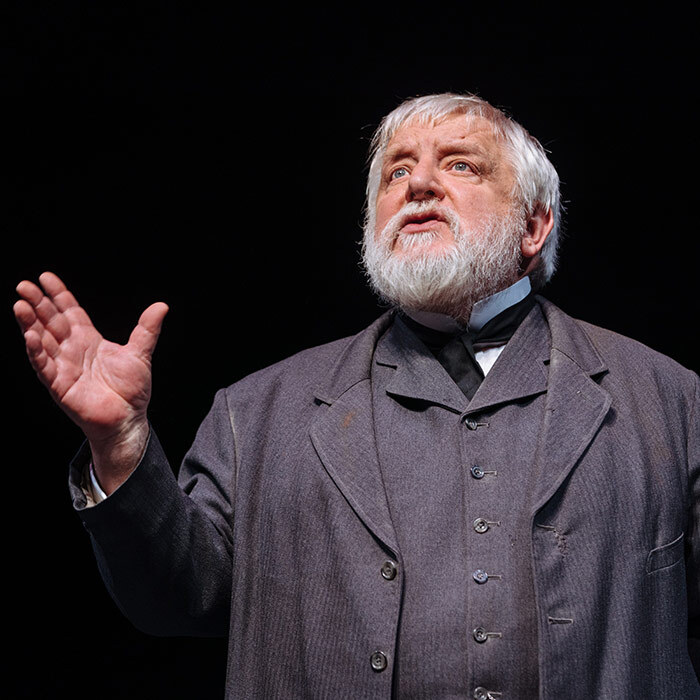

Brian Cox

Nick Clark

Nick ClarkNick is the features editor of The Stage. Previously he was the arts correspondent for The Independent.

Straight after playing a US president on Broadway, Brian Cox is directing the UK premiere of Sinners at west London’s Playground Theatre. The acclaimed actor tells Nick Clark about his love of Shakespeare, garnering a new generation of fans with hit TV drama Succession and why directors should just stick to the text

One of the most gloriously irascible television creations in recent years is Succession’s Logan Roy. Played by Brian Cox, this ageing, wealthy media tycoon, snarls, quips and bellows his way through 20 episodes of the heavily feted Sky Atlantic show.

Yet it is fairly daunting to be confronted with the character in real life. When Cox arrives to talk about his latest project, he does so in trademark Logan Roy outdoor-wear: an unbranded wool baseball cap, scarf and waxed jacket. Fortunately, as he sheds the coat, hat and scarf and settles into the room at the British American Drama Academy in London, so the lingering fears of a furious dressing down to any ill-judged questions dissipate too.

It is something of a moment for Cox. He has just finished an acclaimed run on Broadway, won his first Golden Globe and is awaiting filming of the third series of Succession. He is back in the UK, for a few weeks at least, in the less familiar role of theatre director. “I don’t make a habit of it,” he confides. “I don’t really like directing very much.”

Continues…

Q&A Brian Cox

What was your first non-theatre job?

I’ve only had one job outside the industry. When I was at the National Theatre, we were going to be doing two plays but one was pulled. I was so fed up – I wanted to do film but nothing was happening, so I went and worked as a receptionist at a gym. I was basically resting.

What was your first professional theatre job?

Dundee Rep.

What do you wish someone had told you when you were starting out?

I was very lucky, I had very good influences. Partly because I lost my father when I was very little, I always sought mentorship, and I got it. I had standards that were groomed into me from a very early age and I’m so glad I have those standards. They’ve sustained me. I’ve always listened, and it’s important to listen. Be very wary as you get older to keep listening.

What’s your best advice for auditions?

Always think you’re auditioning them as much as they’re auditioning you. Actors can be guilty of going in with the ‘poor me’ attitude. Just be yourself and ask: are they going to be of value to me? Oh, and learn your lines.

Do you have any theatrical superstitions or rituals?

No.

The show is the UK premiere of Sinners by Israeli writer Joshua Sobol, which is running at the Playground Theatre in west London. The story follows Layla, who is denounced for having an affair with her student Nur and is awaiting the death penalty by stoning.

Nicole Ansari, Cox’s wife, plays Layla, and it was she who first brought the play to his attention. “I read it and thought the subject matter was really interesting,” Cox says. “It’s a subject that is very taboo – people don’t want to go near it. But it’s a quintessential example of female oppression.”

He first directed Sinners at the Hardwick Town House in Vermont in 2016: “The reaction was extraordinary, people said they had never seen anything like it.” Since then, and after a run in Boston, Ansari had wanted to bring it to the UK “because I had a gap between my television show, and I’d just finished a play on Broadway, we could do it now”.

If Cox doesn’t like directing, he doesn’t much like directors either – or at least a particular group of them. “I’m not a big fan of directors, quite honestly; especially when they go all conceptual and it’s all about them, it’s not about the play. They irritate the fuck out of me, a lot of them.”

His exasperation piqued, he continues: “I see these extraordinarily successful directors and think it’s all rather hollow… There’s a lot of dog’s-dinner directing. These fancifully conceptual productions, and you go: ‘Why don’t you just do the play?’ ” He doesn’t name any names.

Are there plays he wants to rescue from the clutches of the conceptualists? “There are,” he says with a weary smile, “but there are not enough hours in the day, and I’ve got a successful career elsewhere.”

Swapping acting for directing

Cox’s career in theatre, film and television spans almost six decades, but beyond teaching in drama schools he has directed only a handful of stage shows professionally, including at Manchester’s Royal Exchange and the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh. He picks out Mrs Warren’s Profession at Richmond’s Orange Tree Theatre in 1989 and “quite a contentious production” of Richard III at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre six years later as among the most memorable.

As a director, “I just want the actors to think,” he says. “Learning how to think is one of the most undervalued things on stage.” His own directorial inspirations all come from his early years in the business, “many of whom are sadly no longer here”. He calls Michael Elliott, father of Marianne, “the finest theatre director I know – a visionary”. They worked together on stage productions including When We Dead Awaken in 1968, The Cocktail Party seven years later and Moby Dick in 1984.

He also picks out Lindsay Anderson – “psychologically one of the best directors I’ve ever worked with” – and Ronald Eyre, who directed Cox at Birmingham Rep soon after he’d left drama school, as key figures in his development.

Cox has played Brutus and Lear at the National Theatre, Peer Gynt in Birmingham, and Petruchio for the Royal Shakespeare Company. But he considers his “greatest classical work” to be the title role of Titus Andronicus, also in Stratford, in 1987.

Much of the credit should go to the director Deborah Warner, he says. “It was an astonishing production. Warner was very fundamental in her approach. It was very text-based and took it to its extreme. That was her incredible gift. She was daring. We started with no set or design. We created the show from the acting, from the group.” Cox won his second Olivier award for the role – four years after winning best actor in a new play for Rat in the Skull at London’s Royal Court.

Starting out at Dundee Rep

Cox was born in Dundee to a working-class family in 1946. From a young age he loved movies and wanted to be a film actor. British films, like the Ealing comedies, “meant fuck all to me” and instead he was inspired by US films starring James Dean, Spencer Tracy – “he was my God” – and Marlon Brando.

But it was someone closer to home who instilled the belief that he could pursue acting as a career. “When I saw Albert Finney, at the age of 14, in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, it was like a shock – like incredible electricity went through my body. There was someone who I didn’t look that unlike doing this work that was incredible. I thought: ‘Wow, so it is possible to be an actor?’ Albert was a totem that everyone looked up to.”

Within a year, Cox was working at Dundee Rep, barely 15 years old and having left school. “I started as the lowest of the low,” he says, taking money to the bank and washing the stage, though really he wanted to be on it. Spoken parts came along and when he met teachers from LAMDA, Cox decided he wanted to go there, “which I did and had the best time ever”.

He went on to work with Finney, and it turned out to be another moment for him, as the older actor told him off for messing around and corpsing on stage. They were doing David Storey’s play Cromwell at London’s Royal Court in 1973 with Pete Postlethwaite and Alun Armstrong. “We were all being a bit naughty. Albert grabbed me and he said: ‘You’re not that fucking good you know.’ It was such a wake-up call.”

Cox started his career “at a time of great social mobility”, and he points to the emergence of working-class actors such as Finney, Alan Bates, Peter O’Toole and Tom Courtenay. “I had a grant, to go to London of all fucking places, to be an actor.” He is dismayed by how that has changed, and believes he would struggle to become an actor if he was starting out now. “We were a lot poorer than we are now. But we don’t do it now; we don’t take care of our people. It’s got worse and worse.”

Cox says he has no interest in calling out actors who went to public school – “good luck to them” – but says theatre has lost the working-class point of view. “People have been removed from it. The working-class voices aren’t there. The writing isn’t there. You had the writing of David Storey and Edward Bond in the 1960s and 1970s when they dealt with working-class stories. Sadly that has been bypassed. Practitioners in the theatre recognise it. It should have moved us in a different direction, and it didn’t.”

He adds: “I kind of blame Peter Hall [former director of the National] for all that, because of the sort of theatre he set up, which was essentially divisive and very middle class.”

Winning acclaim for screen roles

We meet a month after Cox won the Golden Globe for best actor in a television drama in Succession. He lights up when talking about the show. It was clear from the start, he says, that this was an extraordinary part. “I’ve been in this game long enough to know when the red flag goes up and you go: ‘No’. But when the white flag goes up…” he pauses. “This was a triple white flag going up. And given what I had done as an actor over the years, I knew I was the right actor for the role.” He smiles, “Though it’s all very well being the right actor: you also have to deliver.”

The show has built a die-hard fanbase and won critical praise because the writers have tapped into something current in Western society but also deeper into the human condition. “Its roots are classical and universal. There are elements of Lear. The key of where we are living at the moment is that we see entitlement all around us and we see what it’s done and how poisonous it is. We can see it particularly in this shower we have in parliament at the moment and in America with Trump.”

He jabs his finger in the direction of Westminster to emphasise the point. “This shower, this bunch,” he spits out the words, “[Boris] Johnson, what a hideously horrendous human being he is. He’s a liar and seen to be a liar. This is what I find so extraordinary about right-wing politics is that we’ve bought into it. We’re allowing them to be.”

‘Our society is more lost than it’s ever been. Our belief systems are falling apart’

Succession holds a mirror up to nature, to these times, he says. “Of course the audiences love it. They realise that they’re caught on the horns of a big dilemma. They want this and yet they don’t.” He continues: “Our society is more lost than it’s ever been. Our belief systems are falling apart… We are so lost. From the theatre point of view it’s fantastic, because we can continue creating the plays based on the lost boys of the human race.”

There’s a story he’s told a few times, he says, of going to a #MeToo event in Los Angeles, a reading from Ronan Farrow’s Catch and Kill. Afterwards, Cox found himself surrounded by young women, all Succession fans desperate to meet the actor behind the show’s irascible patriarch. “They were saying: ‘Would you mind if I photograph you telling me to fuck off?’ I thought: ‘Is that really appropriate to #MeToo?’ That’s the dilemma: people don’t know where they are.”

There is, he says, “a lot of theatrical influence” in the show. “The cast feels like a company, and we shoot scenes like theatre scenes, and we play them like that.” It also has a number of British playwrights in the writers’ room, including Lucy Prebble, Anna Jordan and Alice Birch. Another theatre connection is through its executive producer Frank Rich, once dubbed the “Butcher of Broadway” when he was the New York Times’ theatre critic, though Cox says he’s “the sweetest, nicest guy and so unlike a butcher – he’s very much a godfather in terms of our show”.

Playing a president on Broadway

Cox has only just finished a run on Broadway, and rather than face a butchering from the critics, his performance as President Lyndon B Johnson in The Great Society, by Robert Schenkkan, was hailed as “electrifying”. The play was, he says, “the most exhausting thing I’d ever done”.

The call came through as he was filming scenes for the finale of Succession’s second season on a luxury yacht in Dubrovnik, and at first he thought they had the wrong Brian – Bryan Cranston had won a Tony award for playing Johnson in Schenkkan’s earlier play All the Way in 2014.

What was initially pitched as a dramatised reading for a month quickly became a full-on Broadway production for two. The problem was there was only three weeks’ rehearsal time and the script was 154 pages long. “I said: ‘That’s a lot to learn, and a hell of a strain.’ But I foolishly agreed. Part of me wants to see if the old muscles are still working. It’s a challenge and at my age it’s a greater challenge.”

With a week to go, Cox knew only 80% of the script. The director suggested an earpiece – the first time he had ever used one – and it worked. He kept it in throughout the run, even after he had learned the lines, though at moments when he paused for dramatic effect, his prompt would jump in.

“And he was right, he was keeping the momentum going. The play was done at enormous speed; there was no time to pause. It was a great lesson: you learn that the rhythm of the piece is as important as anything else and you have to keep it going. I say that to my actors now. ‘Get that thought, get over it, get to the next one.’ ”

Continues…

Brian Cox on…

… the US

“There’s a great bunch of actors here, but in the US it’s more uneven. American theatre is so difficult – I have such admiration for actors there. It’s very hard for them to get purchase because there are no structures. The great thing in this country is we have structures – studios, pub theatre and smaller venues.”

… directors

“The great directors have always been the ones who literally direct, not the conceptual ones. The problem has always been keeping the actor on track and allowing them to do what they can do with the minimum of effort and the maximum effect.”

… directing actors

“Initially, I don’t want them to emote. They will have to eventually, but first they

need to tread the text, and that’s not what you see a lot

of on stage.”

… doing rep

“It was the learning curve of young actors: you went into the repertory theatre system and that was where you learnt and practised your craft and honed it. Then getting into Shakespeare. I’ve always felt an affinity with Shakespeare but I haven’t performed it in a long time.”

… Shakespearean verse

“I’m a Scot, and we have a good sense of rhythm. The link to Shakespeare for me are the sonnets. Because of their form, it’s clear that you can’t mess around with them. Once you get into it you realise what great writing it is. Then you get into the plays and find out the ideas that crop up in the plays…

… the great dames of theatre

“What I admire about actors like Eileen [Atkins], Maggie [Smith] and Judi [Dench] is they still keep their theatrical legs going. They are theatre animals, it’s their tradition, it’s not really my tradition.”

… roles he wants to play

“When I was younger there were roles I wanted to play and I did. As I’ve got older, I’ve allowed things to happen more. I believe in the organic. Like Succession. Two and a half years ago there was no sense of that. Now it’s my life. I open up to the elements.”

It is five years since Cox has appeared on stage in Britain. As part of the 50-year anniversary celebrations of Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum – he had been in the Lyceum’s opening production, The Servant o’ Twa Maisters, in 1965 – Cox starred in Waiting for Godot. It was the first time he had done a Beckett play but acting opposite fellow Scot Bill Paterson was a “no-brainer”, he says. “It was a really good production… We might do it again.”

The idea of a future life for the show didn’t have much traction after the run five years ago, Cox says, with producers making distinctly unenthusiastic noises about their use of Scottish accents. “But now I’ve done Logan Roy and Bill has done Fleabag…” he breaks off and raises his eyebrows sardonically, “there are more positive noises. It’s the usual bollocks, but it’s all part of it.” He is keen to return to the stage in Britain, though he has one caveat. “Just don’t let [Sunday Times theatre critic] Quentin Letts anywhere near it.”

Waiting for Godot review at the Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh – ‘a rare treat’

Cox has managed to create extraordinary stage and screen work over his almost six-decade career, from theatre to TV and then Hollywood blockbusters including the Bourne and X-Men franchises. He was also the first Hannibal Lecter in the film Manhunter in 1986 (though the character was called Lecktor). What’s the secret to such longevity? “You have to keep listening,” he says, “and it’s about reinventing yourself.”

He remembers meeting Nigel Hawthorne, who complained that despite being a leading actor he was getting minor parts in US films opposite stars such as Sylvester Stallone.

“He said: ‘I can’t play small parts anymore.’ I said: ‘Nigel, it doesn’t matter, it’s not important. We get bogged down in this image of who we are. What we have to do is rub the image out, keep reinventing the image and find something different. You worked with Sly Stallone? I worked with fucking Steven Seagal. You won’t be bested on that.’ ”

‘I didn’t want to fall into the pattern of a luvvying British actor. I’ve seen people who have stayed too long at the fair. Fuck off and do something else’

Reading a book by British film director Michael Powell, Cox found a quote that in movies there were no big parts and small parts, “just long parts and short parts”. He says: “That legitimised me when I made the move to America in the 1990s. I didn’t want to fall into the pattern of a luvvying British actor, and I’ve seen it with people who have stayed too long at the fair. Fuck off, go and do something else.”

He adds: “I decided I would be a character actor in movies, and that gave me the credence I’ve got now. And I owe where I am now to that decision in the 1990s. You have to take those risks. You have to take yourself by the scruff of the neck and say: ‘What are you doing? Is it relevant?’”

Sinners runs at the Playground Theatre, London, until March 14

CV Brian Cox

Born: 1946, Dundee

Training: LAMDA

Landmark productions:

Theatre:

• Peer Gynt, Birmingham Rep (1967)

• The Cocktail Party, Royal Exchange, Manchester (1974)

• Rat in the Skull, Royal Court Theatre, (1984)

• Titus Andronicus, Royal Shakespeare Company (1987)

• King Lear, National Theatre (1990)

• Rock’n’Roll, Royal Court Theatre, London; Duke of York’s Theatre (2006)

• The Weir, Donmar Warehouse (2013); Wyndham’s Theatre (2014)

• Waiting for Godot, Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh (2015)

• The Great Society, Broadway (2019)

Film:

• Manhunter (1986)

• The Bourne Identity (2002)

• X2: X-Men United (2003)

• The Carer (2016)

TV:

• Nuremberg (2000)

• Deadwood (2006)

• War and Peace (2016)

• Succession (2018)

Awards:

• Olivier awards for Rat in the Skull (1984) and Titus Andronicus (1988)

• Critics’ Circle awards for The Taming of the Shrew (1985) and Titus Andronicus (1988)

• Emmy Award for Nuremberg (2000)

• Golden Globe for Succession (2020)

Agent: Nicola van Gelder, Conway van Gelder Grant

More about this person

Big Interviews

Recommended for you

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99