War Requiem

In 1962 the new Coventry Cathedral was consecrated, just yards away from the ruins of its medieval predecessor, which was destroyed in a bombing raid in November 1940.

Commissioned for the occasion, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem achieved an instant success, its recording under the composer’s baton selling some 200,000 copies within its first five months – an extraordinary figure for a large-scale contemporary classical work. The piece has gone on to become a staple of the choral repertory, with numerous performances currently taking place worldwide to mark the anniversary of the end of the First World War.

The War Requiem is a unique conception. In addition to the standard text of the Latin Mass for the Dead, Britten includes settings of Wilfred Owen, who died on active service in France just a week before the Armistice, aged just 25.

Over recent years English National Opera has staged several choral works not designed for theatrical presentation. Not surprisingly, results have been mixed: it’s clearly something of a risky practice.

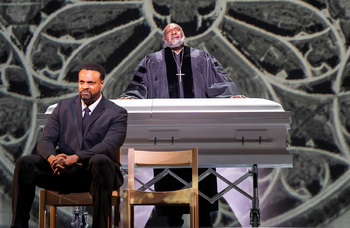

The War Requiem, for instance, contains no characters or narrative, although the two male soloists – here represented by David Butt Philip’s sturdy tenor and Roderick Williams’ eloquent baritone – often sing Owen’s words written as if spoken by soldiers, never more movingly so than in the final poem, It Seems That Out of Battle I Escaped, when it gradually becomes apparent that both the participants – one from each side of the conflict – are dead.

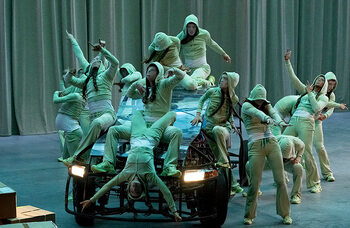

Yet in this instance, as designed by Turner Prize-winning German photographer Wolfgang Tillmans in his first operatic assignment, alongside costume designer Nasir Mazhar and choreographer Ann Yee, the result fuses the emotive words and Britten’s intricate, highly charged music into a visually arresting staging by Daniel Kramer that conjures up compelling imagery again and again.

The grouping of the chorus – an unbeatable combination of ENO’s own regular forces with those assembled for the recent production of Porgy and Bess, all trained by James Henshaw, plus the Finchley Children’s Music Group and additional child actors – is masterly in its variety and conviction.

Other conflicts – such as the Bosnian War, and recent violence instigated by Polish nationalists – are referenced in a laying-bare of the innumerable crimes perpetrated in the name of armed struggle that the pacifist composer would surely have endorsed.

Musical values represent the company at the very top of its game, with soprano Emma Bell alternately portraying a seer-like figure and a universal mother, her empowered vocalism setting the seal on the central trio of principals.

ENO’s orchestra conveys the subtlety as well as the sheer power generated by Britten’s angry, anguished score, of which conductor Martyn Brabbins, the company’s music director, proves an inspired interpreter.

Daniel Kramer: ‘Opera is so important, so stop coming for our building. Back off’

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99