The Importance of Being Earnest

Dominic Dromgoole’s Classic Spring season, a year-long celebration of the plays of Oscar Wilde, began with a production of A Woman of No Importance that, while almost defiantly traditional in its staging, provided a reminder that Wilde was not just a churner-out of impeccable epigrams but a writer of compassion, alert to the societal pressures placed on women.

The season ends with The Importance of Being Earnest, Wilde’s last play and one of the most immaculately crafted stage comedies of all time. Michael Fentiman’s pantomimic production does it a disservice. Denuded of nuance, it reduces every character to a caricature and pitches the comedy at such a frenzied level from the outset it allows it nowhere to go and no space to grow.

Sophie Thompson plays Lady Bracknell like a combination of Maggie Smith in the later series of Downton Abbey, on dowager-autopilot, and a drawing by Gerald Scarfe, chin tilted towards the ceiling, twit-twooing her vowels. Gwendolyn (played by the usually brilliant Pippa Nixon) spends her early scenes angling her crotch towards Jacob Fortune-Lloyd’s Jack, in a way no human woman has ever stood or behaved. Fiona Button’s Cecily battles valiantly against this excess, as does Stella Gonet’s Miss Prism, but it’s not a fight they can win.

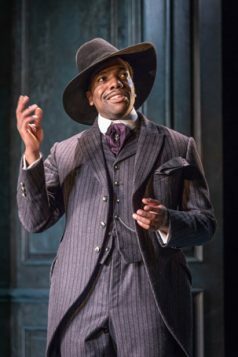

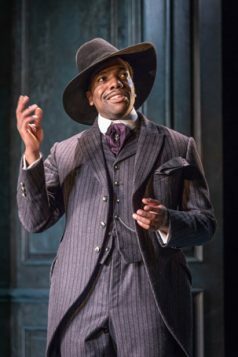

Nor does Fentiman appear to trust his audience to decode the play’s exploration of double lives and the hypocrisies of the age. He insists on making the subtext text by making Fehinti Balogun’s Algernon a man of roving eyes and hands. Balogun’s Algie has a knowing relationship with his butler Lane that ends with them locking lips and he later engages in some baffling and weirdly aggressive semi-sexual nose-rubbing antics with Jack. It’s all so dismayingly blatant, something not helped by the fact that both men bring a wired, perspiring quality to their performances.

The second half fares better, thanks in part to Button’s lightness of touch. She has a pleasingly warm stage presence. But just as the imposing teal walls of Madeleine Girling’s set remain in place even after the play relocates to the country, so the slightly frantic, forced tone remains. It feels primarily like an issue of direction. The cast all perform at the same fevered pitch. The dresses are splendid, though, as they have been in all the productions.

This was a season that set out to hymn Wilde in the West End, to present a portrait of the man, his politics and his art, launching in the year of the 50th anniversary of the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Some of the productions have achieved that with flashes of humanity and pathos amid the quips, but this last one, of his best-known play, has all the subtlety of a meat tenderiser. It’ll sell well, no doubt, but it’s a clunker of a production.

More Reviews

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99