The House of Bernarda Alba

In Jenny Sealey’s production of The House of Bernarda Alba words wrap around the stage. Graeae’s co-production with the Royal Exchange uses a mixture of speech, BSL, captioning and audio-descriptive elements to explore and explode Lorca’s play.

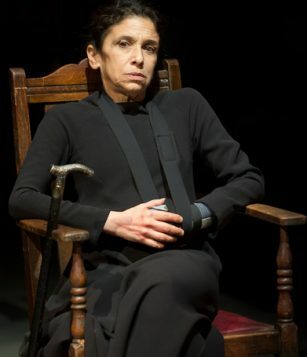

Kathryn Hunter plays the matriarch who, on the death of her second husband, imposes a strict eight-year period of mourning on her five daughters. She has already prevented them from having any form of relationship, now she seeks to isolate them further, to put a lock upon their lives. The in-the-round space adds to the sense of enclosure. Within this circle, Hunter vibrates. She is determined to exert control over her daughters. Protection is entangled with punishment.

Lorca’s play is a response to a world that is hostile to women. It is a play of power and powerlessness, suppression and silence. With its all-female cast (as well as an all-female creative team) the Graeae production is concerned with bodies and voices, visibility and control, in a way that feels depressingly timely.

The cast is a mixture of D/deaf and disabled performers and Jo Clifford’s adaptation has been reworked to accommodate this – the results are often fascinating, reframing the play in interesting ways. Captioning screens are dotted around the stage. Audio description is woven into the text. One of the sister’s steals the other’s prosthetic leg and Hunter occasionally snaps at EJ Raymond’s maid when she stops signing. Two of the daughters are deaf – Hermon Berhane and Nadia Nadarajah (who previously starred in Deafinitely’s innovate production of Grounded) – and the use of BSL is part of the texture of the piece. The intimacies of the sisters are further revealed in this way: who signs for whom, who speaks for whom. It adds extra resonance to the play’s themes of isolation and complicates Bernarda’s need to protect/control her daughters.

Liz Ascroft’s set, with its patterned floorboards and heptagonal arrangement of chairs, makes effective use of the Exchange’s playing space. When the daughters swap their mourning garb for white nightdresses the image is striking. There are times when it feels like Sealey’s production might benefit from more tension – there’s a lot of talk of heat but we don’t really feel it – but it successfully creates its own world. Desire is very much part of the fabric of the play too. It’s full of sexual want and longing.

There’s a convincing mixture of rivalry and affection between the sisters and a pleasing lightness of touch to some of the performances. The whole piece feels collaborative. Kellan Frankland makes an impressive debut as Martirio and Nadarajah’s yearning is palpable as the oldest daughter. Hunter is her usual magnetic self, at once frail and fearsome, cruel and quick; wielding her symbolic silver-headed cane, she’s a tiny mistral in a widow’s weeds.

Sealey’s production – like last year’s Donmar Warehouse Shakespeare trilogy – is also cheering in the way it peoples its stage, for the way the cast take this play and makes it their own.

More Reviews

More about this organisation

Adjusting to Covid-19 crisis helps us appreciate everyone’s needs

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99