Mike Bartlett’s new blank verse play about the 2024 US presidential election is not always satisfying but front and centre is a stupendous turn from Bertie Carvel as Donald Trump

The Trump years already feel like a bit of a fever dream. Mike Bartlett’s new blank verse play, a successor of sorts to his royal opus King Charles III, taps into that heightened, malevolent energy in a fantastical account of the US presidential election campaign to come in 2024.

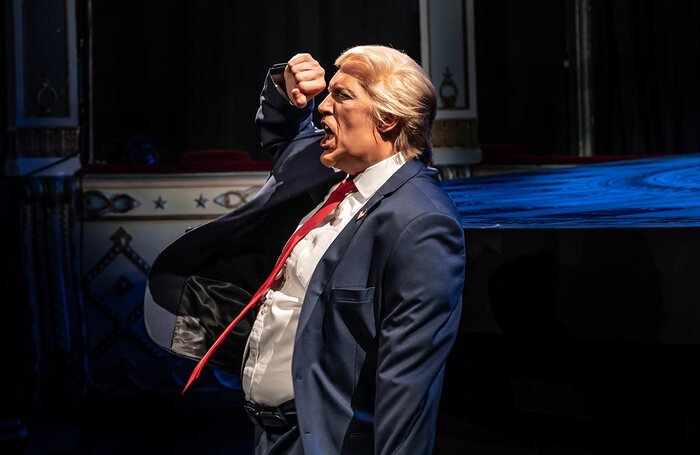

Front and centre is a stupendous turn from Bertie Carvel as Trump, adding to his list of transformative performances. Yes, he’s got the padding and the wig, a floating shelf of fried-nylon, but it’s more than just make-up, it transcends Saturday Night Live caricatures. He completely nails the smug, elastic grin and jabby hand gestures, and appears to have made his mouth change shape entirely. He has the man’s manner down to a golf tee: the barely concealed threat, the self-adulation, the weird prissiness. It’s uncanny.

Lydia Wilson also excels as favourite child Ivanka, in tailored dresses and teeteringly high nude heels, a calm, calculating presence, a counterweight to his ugly bluster.

The plot sees vice president Kamala Harris (played by Law and Order: SVU’s Tamara Tunie) inheriting the top job just as Trump declares his intention to run again. Further narrative twists follow, with Bartlett lacing his play with Shakespearean allusions – a bit of Lear here, a nod to Richard II and III (though when Ivanka squares off against her dim siblings it’s hard not to think of Succession).

Bartlett also uses the characters of young Trump-supporter Rosie (Ami Tredrea) and her left-leaning journalist brother Charlie (James Cooney) to unpack the mechanics of populism from ground level, trying to understand how a cartoonish billionaire with a bleached Bagpuss on his head can become, to some, a symbol of liberty.

The play is not an exercise in crystal ball-gazing, rather a reflection on the ripples caused by the Capitol attacks and the repercussions for American democracy. If the left only acts as a corrective to the right, if it focuses on what it isn’t, rather than what it is, it creates a space into which figures like Trump can flourish. In later scenes, when he’s imprisoned, he takes on an almost Hannibal Lecter-ish quality, becoming a martyr and a figurehead for an increasingly volatile mob.

Designer Miriam Buether’s set combines Dr Strangelove’s war room with an expensively anonymous hotel lobby, on to which, at one point, a golf-cart trundles. Rupert Goold capably marshals the large cast and the very plotty plot but, at times, the play’s twisty ambition works against it. The first half establishes a lot of themes and threads that it can’t resolve in a satisfying fashion, narrative elements are terminated abruptly and moments you feel should be chilling are oddly downplayed – though Cherrelle Skeete, as a nurse talking about her mother’s lonely death from Covid-19, adds a welcome emotional note to the play’s later stages. It’s Carvel who leaves the biggest impression, bestriding the production in a magnificent and grimly apposite fashion.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99