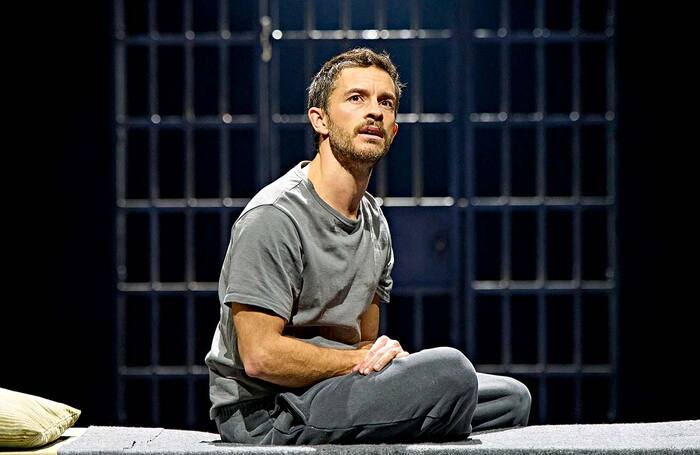

Richard II review

Jonathan Bailey glitters in Nicholas Hytner’s lucid staging of Shakespeare’s history play

Shakespeare’s poet king is back, and he’s making one hell of a scene in this typically lucid, thoughtful production from Nicholas Hytner. Played by Jonathan Bailey of Netflix’s Bridgerton and the movie Wicked, this monarch is dangerously deluded, flamboyant and charismatic, with a deep vein of spite and self-obsession. Hytner is far too shrewd a director to serve up this drama of power and politics with any crude 21st-century parallels attached, but its exploration of statesmanship – and what we really mean, want or need when we talk about strong leaders – inevitably feels current in our unstable world. The staging is solid rather than exceptional. But Bailey makes a transfixing Richard, his plight engaging to the last, despite the nastier excesses of his capricious behaviour.

Richard’s reckless, even obnoxious conduct is motored by his utter conviction in his right to rule; we may no longer believe in the divine right of kings, but some of today’s political leaders apparently hold a similarly rock-solid faith in their own entitlement to their position. Bob Crowley’s traverse set is a chandelier-studded corridor of power, and Bailey swaggers and swishes its length, handed the crown in a ministerial-looking box by a functionary and handling it with obvious relish. Grant Olding’s fidgety, doomy underscoring has shades of dynastic TV drama Succession, and the tone here flirts with inky comedy and even farce, as Bailey’s arrogant assurance is pricked and finally brought crashing down in a coup led by Royce Pierreson’s wily, hard-headed Bolingbroke.

Flinging out bitchy aperçus and florid pronouncements, and passing life-changing edicts on a whim, Bailey’s is a Richard who is instantly guaranteed to make enemies. His boredom with the actual business of affairs of state is flagrant, and we see him lounging, snorting cocaine and enjoying some homoerotic flirtation with his hangers-on, or kicking the walking frame out from under a frail John of Gaunt (on press night, Martin Carroll standing in for an indisposed Clive Wood). Besotted with his own celebrity, he heedlessly courts laughs by flinging out cruel jokes and, on hearing of violent rebellion erupting in Ireland, is most immediately preoccupied by the attention-grabbing opportunity he thinks it offers to play the conquering hero.

Contiunues…

He’s perilously insulated from the lives of those he rules – a Gloucestershire-set scene sees him wandering through litter-strewn dereliction, nose wrinkled in undisguised disgust – and when challenged, Bailey flies into a defensive rage, panicking as it becomes obvious how fatally he is out of his depth. During the famous speech that begins “let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings”, he succumbs to an almost childlike terror, confronted by his human vulnerability. The scene dissolves into the arrival of Pierreson’s Bolingbroke with artillery – deadly hardware come to crush Richard’s hollow illusion of power.

When the crunch comes, this Richard clings on doggedly, summoning Bolingbroke to seize the crown as if the usurper were a wilful puppy, and smashing a mirror against his forehead, shattering his own deceptive reflection. It’s a glittering performance in an uncluttered setting: proficient, measured, the production permits Bailey’s doomed, vainglorious Richard to shine.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99