One Night in Miami...

Four men. One motel room. Kemp Powers’ 2013 play One Night in Miami is inspired by true events. After winning the world heavyweight championship in 1964, Cassius Clay spent the night in a motel with Malcolm X, Jim Brown, and Sam Cooke. The next morning he would announce his intention to change his name to Cassius X, later Mohammad Ali, and join the Nation of Islam.

Powers imagines what might have gone on behind that door, with only ice cream in the freezer (vanilla, ironically). With no booze to drink and no tail to chase, they end up talking – about race, power, and the importance of being seen and being heard in the world.

All four of men are at pivotal points in their lives and careers. Clay’s riding high on his win against Sonny Liston, while Malcolm X will soon split from the Muslim Brotherhood. Cooke has just recorded the song he’ll be remembered for – the song that Barack Obama would quote from on the night he was elected – A Change is Gonna Come, while football star Brown has decided to make the switch into films, though he doesn’t want to be another Sidney Poitier, he wants to be an action hero.

The men talk about how success doesn’t shield them from bigotry, they talk about skin colour and levels of blackness. Malcolm X argues that Cooke softens his sound for white audiences, Cooke responds by saying that more people will hear him that way and that besides he owns the rights to the songs, so he’s the one making the money. Brown, meanwhile, hopes he’ll eventually get to star in a film where the black guy doesn’t get killed in the second reel.

Powers’ play is not structurally adventurous. The men conveniently vacate the room at regular intervals to allow other conversations to take place, and it often feels as if they’re explaining things to each other they would already know.

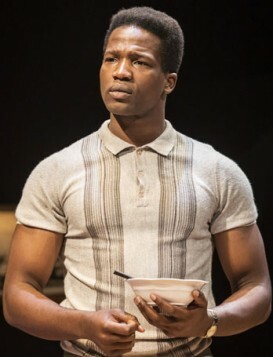

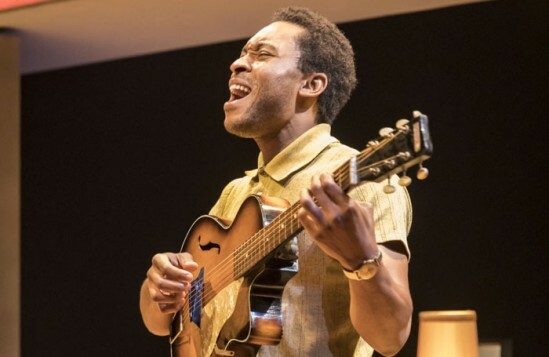

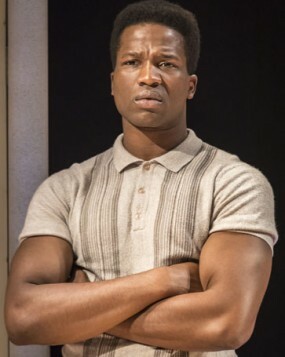

Kwame Kwei-Armah’s production, a version of which was staged at the Baltimore Drama Centre last year, can also feel static at times, but it benefits from an incredibly charismatic cast, all of whom are successful in humanising these mythic individuals.

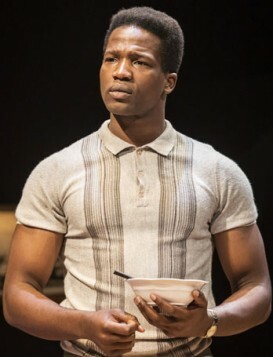

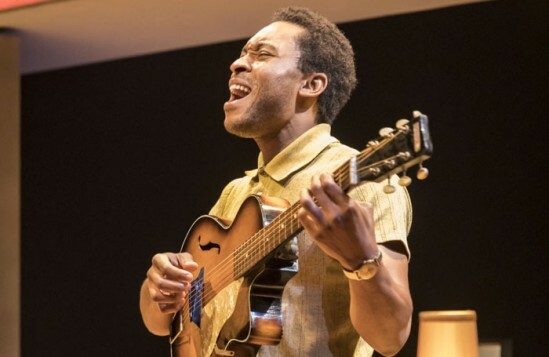

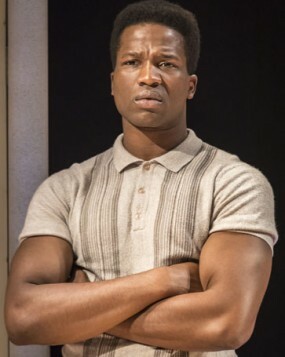

Sope Dirisu captures Ali’s youthful vigour and sublime confidence even if he lacks the man’s magnetic intensity. When Arinze Kene’s Cooke serenades the audience with You Send Me, it’s a seriously sweet moment. But it’s Francois Battiste’s Malcolm X who emerges as the most complex character – he’s on a different point in his journey to the rest of them.

While Powers hints at these men’s flaws – particularly in regard to their absent wives – the play he’s written is first and foremost one about greatness, legend and legacy. Its reach is long. These men’s stories matter because of who they were, but also because the things they hoped for have not yet come to pass, because two of them would die as a result of violence, because, as the song goes, far too many people’s heroes still don’t appear on stamps.

More Reviews

More about this person

More about this organisation

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99