Irish Annie’s review

Warm-hearted, toe-tapping musical craic

They may not dye the Mersey green on St Patrick’s Day, but Liverpool can still lay a claim to being one of the most Irish cities outside the Emerald Isle. It is a place indelibly shaped by 19th-century mass migration, with 75% of the current population claiming Irish heritage. A ready audience, then, for writer and musician Asa Murphy’s touring celebration of the craic you might find in any of the Irish bars or clubs dotted about the city and beyond.

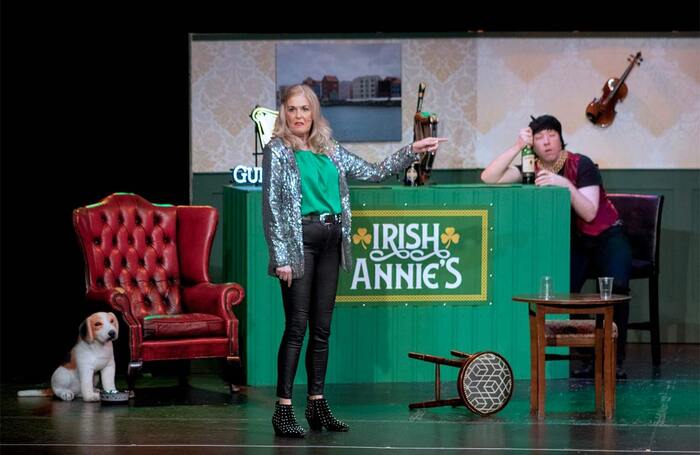

Wesley Jones’ fold-out set certainly resembles one such drinking den, with its functional tables and stools, button-back armchair, resident dog and a bar on which the Guinness pump glows like a golden beacon. Murphy’s show is billed as a musical play, but it doesn’t have the traditional narrative arc that suggests. Instead, it is an interactive fusion of gig theatre, cabaret, stand-up and even panto: Pauline Donovan’s baddie Moira the Money Lender has a little black book that contains not only the debts of the roll call of misfits on stage, but a sly shout-out to selected audience members, too. And the fourth wall is not so much broken as never erected in the first place, with everyone in the auditorium embraced as part of a crowd that has converged on the bar run by the titular Annie.

Continues...

Catherine Rice’s landlady is a Catherine wheel, sparking fiercely – almost alarmingly at times – as the big-hearted hostess of a party where her ragtag of regulars are encouraged to share their stories in turn between bursts of music. Among them is Ricky Tomlinson, rather incongruously playing himself, albeit in Jim Royle’s signature mustard T-shirt, and mixing random anecdotes about his life and career with an audience quiz featuring questions that could have been pilfered from a box of Christmas cracker gags.

Writer and director Murphy maintains a steadying hand on the tiller from his perch playing Seamus, leader of the Shenanigans – a five-piece band that includes John Wheatcroft on guitar and mandolin, and plays a mixture of original ballads written by Murphy himself, and rousing, traditional singalong tunes such as The Wild Rover and Dirty Old Town.

It’s unpretentious, crowd-pleasing stuff with a touch of genuine pathos courtesy of Sam Conlon’s bar-propping alcoholic Noel, who breaks off from quoting Shakespeare and Yeats to explain sorrowfully how drink destroyed his acting career and to sing a poignant Danny Boy, reducing the room to spellbound silence, followed by a spontaneous standing ovation. And if there is not much of a plot to underpin proceedings, there is a palpable sense of community spirit that strikes a resonant chord with its audience.

More Reviews

Recommended for you

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99