Hamlet with Ian McKellen review

Ian McKellen continues to experiment in this dance version of Hamlet, but despite good moments this is a stiff and overwrought production

The Edinburgh Fringe has hosted musical versions of Hamlet, bouncy-castle Hamlets, Shit-Faced Hamlets. Now Ian McKellen and choreographer Peter Schaufuss collaborate to make a song and dance about Shakespeare’s play.

You have to admire the ever-game McKellen and his willingness to keep experimenting at the age of 83, but although bold it’s a misconceived hybrid. It’s not helped by a venue – for several glorious years home to the visual and physical theatre programme of Aurora Nova – which is not blessed with the soundest acoustics. Throw in some musical underscoring and the great McKellen’s contributions often lack the sweet clarity we expect and love.

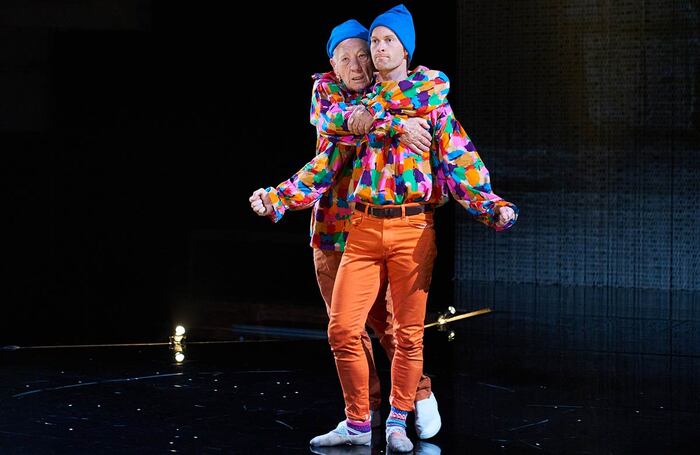

It’s a pity because Hamlet is often talked about as a man in two minds, and here that is made physically manifest. Johan Christensen dances Hamlet and McKellen speaks some of drama’s most famous lines. It’s an interesting idea, with the two often wandering the stage like conjoined twins then separating and coming together like mercury.

There are moments when Christensen’s floppy-haired youth and McKellen’s gnarled old age create a kind of double vision, a ghosting. That’s interesting in a play full of ghosts, featuring a prince who will never grow old. When Christensen’s prince violently rejects Ophelia (Katie Rose), the older version of himself comforts her with a wistful tenderness. McKellen speaks “to be or not to be” directly to his alter-ego. Often the older Hamlet appears to be observing his other self with a kind of sorrow.

So far so interesting, and there are other good moments and ideas at work here too. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are a comic double act, a bit like Tweedledum and Tweedledee. Obvious, but quite fun. When Hamlet feigns madness, the pair don Pierrot-inspired costumes like a couple of gleeful clowns. Occasionally the choreography sparks into full-blown life: a duet between Hamlet and Ophelia is a pretty good expression of dance as a vertical manifestation of perpendicular desire.

But too often the choreography feels like an earnest illustration of the play, sometimes the pageantry of the staging makes it feel stiff and overwrought, and the way it presents the sexual politics – Ophelia is the virginal figure of Millais’ painting; Gertrude (Caroline Rees) a bit of a vamp in a split, thigh-length red dress; Horatio is so inoffensively wholesome you could dunk him in your tea and eat him – seems stuck in the mid-20th century.

Anyone staging a classic play, in whatever form, needs to ask themselves the question: why this play and why now? Nobody has done that here. It’s a reminder that a concept alone, however clever, is never enough. You have to have something to say if the play is going to speak to us. Here it barely whimpers.

More Reviews

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99