Hamlet review

Shadowy, impressionistic Hamlet starring a forthright Billy Howle

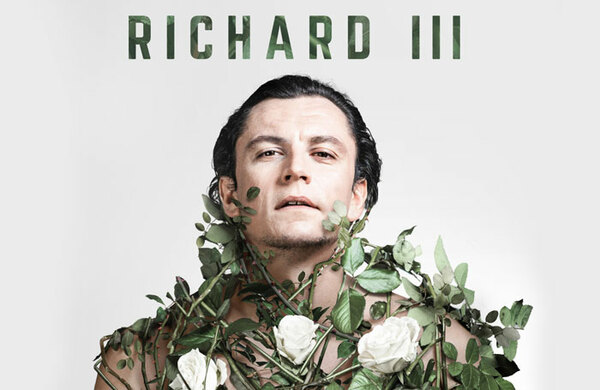

Like his Richard III for Headlong in 2019, director John Haidar’s Hamlet is set in a dark, shadowy world, where the corridors of power are painted black. Alex Eales’ design is inspired by the real Danish castle on which Shakespeare based Elsinore, with long staircases, adjoining rooms and gauze screens granting only the illusion of privacy. Suggesting a labyrinthine place, the set revolves, and spaces open up and close off. Under Malcolm Rippeth’s lights, a huge, imposing slatted wall appears to quiver and bend at the appearance of Hamlet’s father’s ghost. Nothing here is stable, or to be taken at face value.

This makes sense for Hamlet, a play in which the title character’s sense of reality comes crashing down, memory in the form of a ghostly apparition becomes his guiding beacon of truth, and his famous "madness" takes hold. As Hamlet, Billy Howle is boyish and sulky in a Joy Division T-shirt (in Natalie Pryce’s costume design, he of course wears only black), turning increasingly aggressive. He reserves the most venomous of his outbursts for the women in his life, Ophelia and Gertrude; there’s more than a touch of the incel about this prince.

To resist the upending of his world as he knows it, he carries with him a tape recorder and a determination to document, gather evidence, set the record for posterity. Hamlet is often a frustratingly maudlin character, yet Howle injects him with a sense of purpose and action – a reaction against the many uncertainties that plague him. To be or not to be? This is a Hamlet who chooses to be – at least until he has done what needs doing.

There is full-blooded support from the rest of the ensemble. Jason Barnett is particularly enjoyable as the foolish Polonius, whose pompous ramblings provide welcome comic relief. Firdous Bamji makes a lasting impression as the Player King, a seasoned tradesman who lends real import to his tragic speech and highlights Hamlet’s preoccupation with theatre as a medium in which fakery and fiction reveal truths and hold “the mirror up to nature”.

Video design by Jack Phelan suggests another kind of mirror, projecting home video footage of Hamlet as a child. Recorded memories play an important role, something concrete in a court of lies and forgery. The ghost, after all, implores Hamlet to remember, when it seems everyone else has forgotten the late king. It’s an elegant idea and suggests a real warmth in Hamlet’s relationship with his father. But Haidar employs it sparingly, using the home video only in brief bookending moments. It is a shame these interpretive gestures don’t infiltrate the substance of the play more. How reliable are these documents – or might they also contain their own fictions?

More Reviews

More Reviews

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99